Defective Products and Product Warranty Claims in Minnesota

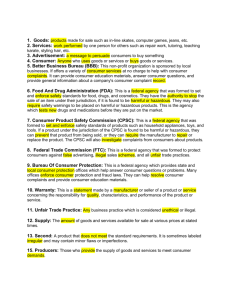

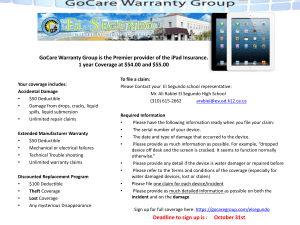

advertisement