Chapter 9 Product Liability

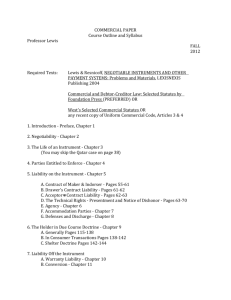

advertisement