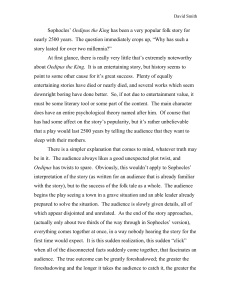

Oedipus: From Man to Archetype

advertisement