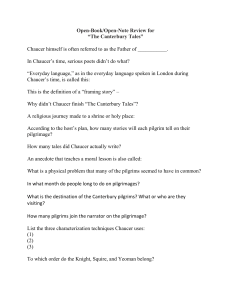

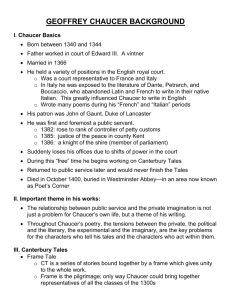

The Canterbury Tales

advertisement

Geoffrey Chaucer The Canterbury Tales Possible Lines of Approach An unfinished masterpiece? Chaucer the Pilgrim and Chaucerian irony Gender and sexuality The role of the Church Estates satire Frame and tale Pilgrimage Other Notes on Approaching The Canterbury Tales Form Connections Questions for Discussion Critical Viewpoints/Reception History Appendices Appendix 1: A Note on Chaucer as “The Father of English Literature” Appendix 2: Some Notes on Medieval Ideas about Humanity and the Cosmos Appendix 3: A Brief Summary of The Canterbury Tales Appendix 4: Expanded Summary of Anthologized Canterbury Tales Texts Appendix 5: Ideas for Classroom Exercises Appendix 6: Some Helpful Resources for Teaching The Canterbury Tales Possible Lines of Approach An unfinished masterpiece? Noting that The Canterbury Tales does not adhere to the original plan outlined by The Host (see “Overall Synopsis”), literary critics through to the middle of the twentieth century tended to discuss the text as an abandoned or unfinished project. More recently, however, several scholars have argued that the collection seems to have an overall “story arc,” with a definite beginning and conclusion. They have suggested that changes to Chaucer’s plan are recorded several times within the text itself, so the work we now read may be more complete than earlier critics allowed. Discussing The Canterbury Tales from this angle could give students a useful way of grappling with the connections and contrasts among the stories they have read. Although your students probably will not have much sense of the entirety of the Tales, they still should be able to find several thematic strands that run through at least two of the pilgrims’ tales. Chaucer the Pilgrim and Chaucerian irony One of the unusual aspects of The Canterbury Tales is that Chaucer makes himself (or, more accurately, a version of himself) one of the characters. This helps to create what scholars call “Chaucerian irony,” because Chaucer the Pilgrim seems quite gullible. For instance, he calls the Shipman, who is a murdering pirate, “a good fellow.” Although your students will most likely not be reading Sir Thopas, which is Chaucer the Pilgrim’s first attempt at storytelling, it is worth noting that it is a parody of the popular romance genre and the poets who write romances—and an abject failure. The Host interrupts this ridiculous performance to demand something better, the only such instance in the Tales. Florence H. Ridley quotes one undergraduate lament in response to Chaucerian irony in her introduction to the MLA’s Approaches to Teaching Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales: “I think it would be helpful to explain on the very first day of class that Chaucer never means what he says.” Chaucer’s ironic relationship to the self he invents for the Tales and to the tales themselves can lead frustrated students to agree with Ridley’s anonymous respondent, but it can also provide an excellent occasion for a discussion of the crucial difference between the author and the narrator or authorial persona. Students may also seek solace in the fact that many highly intelligent, prominent scholars entirely missed Chaucer’s literary gamesmanship in the early days of Chaucer criticism. Gender and sexuality The societal situation of women and of men, as well as their relationships with each other, is one of the central themes of The Canterbury Tales. This is particularly true of what critics since George Lyman Kittredge (1911-1912) have called “The Marriage Group.” This set of stories, beginning with The Wife of Bath’s Tale and including The Merchant’s Tale and The Franklin’s Tale (with a few interventions from other pilgrims) is generally regarded as a kind of debate about the relationships women and men should and/or do maintain within marriage. Of course, sex and gender also play into many other tales in this collection. Chaucer was one of a very few English writers of fabliaux (singular fabliau), a genre that originated in France consisting of short and satirical bawdy stories (see the introduction to the volume for a brief discussion). The Miller’s Tale is an example of this genre; it frankly explores the politics of sex. Chaucer’s portrayals of women are diverse, including innocent maidens and domineering businesswomen, merciful and revengeful queens, patient and conniving wives, wise counselors, and vain scolds. Thus, a discussion of the poet’s attitudes toward and depictions of gender, and women in particular, is one of the most thriving areas of Chaucerian scholarship. Some scholars have noted that the Pardoner is described as indeterminately gendered in the General Prologue and have questioned the nature of his relationship with the Summoner. The role of the Church The Catholic Church had immense influence, both worldly and spiritual, during the Middle Ages. As with most powerful institutions throughout history, corruption was widespread. During Chaucer’s time, satirical writings about the Church and the clergy were quite popular; the Tales reflect these literary traditions. The Monk’s and the Prioress’s portraits in The General Prologue, as well as The Pardoner’s Prologue and Tale draw on criticisms of religious officials found in estates satire (see separate entry below). Some of the tales are clear examples of antifraternal satire, which was aimed at the abuse of charity many people perceived in the friars, who made their living by seeking contributions from the faithful—and sometimes apparently made a considerably better living than their parishioners, despite a vow of poverty. The portrayal of the humble Parson exemplifies another literary tradition about medieval religious writing. This worthy man is described in the General Prologue as a compassionate and steadfast example of goodness, and he rounds off the Tales with a tract on the need for penance that leads directly to Chaucer’s own Retraction of his secular works. Estates satire Medieval theorists divided society into three major “estates” depending upon social status and profession. The First Estate was the Church, composed of the clergy, “those who pray.” The Second Estate was the Nobility, composed of knights and lords, “those who fight.” And the Third Estate was the Peasantry, “those who produce,” supporting the first two estates by producing food and other necessary items. Women were thought to be secondary members of the three social estates, depending upon which of these three groups they belonged to, but there were also supposed to be “three feminine estates” defined by a woman’s sexuality: she was a virgin, a wife, or a widow. An important literary genre, called estates satire, grew out of these concepts. Generally speaking, estates satire points out the ways in which various estates and their members fail to live up to the ideals of their positions. Since the work of Jill Mann in the 1970s, the General Prologue of The Canterbury Tales has been widely understood to have drawn on this tradition, which also includes portions of John Gower’s Mirour de l’Omme [Mirror of Man] and William Langland’s Piers Plowman. Most critics agree that Chaucer’s brand of estates satire is more subtle and ironic than the norm, which is perhaps why critics took some time to recognize his use of the genre. Examples of the First Estate in the General Prologue include the Knight, the Squire, and the Yeoman. The Second Estate is represented by the Parson, the Prioress, the Monk, the Friar, the Summoner, and the Pardoner. The Third Estate is embodied in the Plowman, the Miller, and the Reeve, among others. You will notice that the first character in each list is a representative of the ideals that should be upheld by each estate and stands in sharp contrast to the others. Frame and tale By writing a frame tale, Chaucer was engaging in a centuries-old literary tradition and following the example of his Italian contemporary Boccaccio, author of The Decameron, as well as that of his friend John Gower, author of the Confessio Amantis [Lover’s Confession]. Frame tales are collections of stories gathered together by the device of a larger plot, often one involving a storytelling competition and/or a series of stories presented by a narrator to a listener as a form of education. In the case of The Canterbury Tales, the frame consists of the pilgrims’ travel to the shrine at Canterbury and their interactions during the tale-telling contest they participate in on the way. In the hands of a skilled writer, frame tales can offer not only a cleverly connected collection of interesting tales, but also an ongoing commentary on the nature of storytelling performances and of writing itself. Chaucer’s skill at adapting stories to their tellers and including a version of himself as one of the tale-tellers creates complex interactions between the frame and the stories it contains. Pilgrimage Pilgrimages are trips to visit holy places, particularly saints’ shrines, which usually contain the saints’ remains and, sometimes, items associated with them (both of which are called relics). They allow worshipers to demonstrate devotion and repentance, as well as seek favor from saints and/or God. In the Tales, the pilgrims travel to the tomb of St. Thomas à Becket, former Archbishop of Canterbury, who was killed in 1170 by knights associated with Henry II. Pilgrimage has a long history as a metaphor for life itself and is used in that sense in the frame and within the tales themselves. Other Notes on Approaching The Canterbury Tales Form When writing in verse, Chaucer used either iambic tetrameter or iambic pentameter. By the time he began work on The Canterbury Tales he wrote primarily in iambic pentameter. Chaucer seems to have been the first poet to use this meter in English; he seems to have devised it by combining the iambic speech patterns common to English speech with the pentameter line then used in continental Europe. Iambic pentameter has been an exceptionally influential and popular meter: Shakespeare, among others, wrote predominantly in that meter. Connections within The Broadview Anthology of British Literature Marie de France, Breton lays, p. 158 “Betwene Mersh and Averil” (Middle English Lyrics), p. 190 “The Lady Dame Fortune is both frende and foe” (Middle English Lyrics), p. 196 “I have a gentil cock” (Middle English Lyrics), p. 196 From The Owl and the Nightingale, p. 312 Geoffrey Chaucer, “To His Scribe Adam”, p. 484 Selections on Monks, Anchoresses, and Friars, p. 559 From The Miracles of Thomas of Becket, p. 569 From Account of the Heresy Trial of Margery Baxter, p. 579 Readings on The Persecution of the Jews, p. 580 Questions for Discussion 1. In what ways have The Canterbury Tales surprised you, and in what ways have they been what you expected? Comment on your reaction. 2. One of the important concepts scholars have discussed in their work on The Canterbury Tales is the tension between what Chaucer calls “earnest” and “game.” Such tension seems to occur on several different levels and in several different tales. In what tales do you think Chaucer is being earnest, and in what tales do you think he is playing a game? Does he ever seem to be both earnest and playing a game? 3. What difficulties have you had in your encounter(s) with Chaucerian texts? Which of those difficulties do you think are the result of historical distance from Chaucer, and which do you think are a more deliberate part of the text? Do these hurdles and frustrations reveal anything interesting? 4. Often cited as one of the “Big Three” English poets (along with Shakespeare and Milton), Chaucer has come under fire during the past few decades as the author of canonical texts that privilege the authority of wealthy Englishmen over that of others. In what ways do you think this argument might be reasonably supported? In what ways do you think it could be refuted? 5. In part because of his ironic stance, Chaucer’s attitude toward women has been the source of constant debate among scholars. How would you characterize Chaucer’s depiction of his female characters? 6. During the bloody religious conflicts that would envelop England during the sixteenth century, Chaucer was cited both as a pious defender of the established Church (by Catholics) and as a firebrand exposing Church corruption (by Protestants). How are such radically different interpretations possible? Where can you find evidence for or against these claims? 7. What human qualities does Chaucer seem to value? Are there times when those views conflict with the social values to which you are accustomed? If so, how? Critical Viewpoints/Reception History The famous retraction at the end of The Canterbury Tales seems to indicate that Chaucer not only had some expectation that his work would be remembered and read after his death, but also that he wished to direct future readers’ interpretations of his oeuvre. The frequent slipperiness of Chaucer’s narrative persona and the commonality of pious authorial retractions in medieval, however, make it extremely difficult—perhaps impossible—to determine just how Chaucer wanted to teach his audience to read his texts. When he tells us to reject most of the tales modern readers find particularly compelling and embrace those which most of us like least, can he be serious? Is this apparent disjunction the result of a great gap separating Chaucer’s age from our own, or is it one last, grand irony? Richard Brathwait (1665), from A comment upon the Two Tales of our Ancient … Poet. Sr Jeffray Chaucer … The Miller’s Tale [and the] Wife of Bath: A Critick … said ‘that he could allow well of Chaucer, if his Language were Better.’—Whereto the Author of these Commentaries return’d him this Answer: ‘Sir, it appears, you prefer Speech before the Head piece; Language before Invention; whereas Weight of Judgment has ever given Invention Priority before Language. And not to leave you dissatisfied, As the Time wherein these Tales were writ, rendered him incapable of the one; so his Pregnancy of Fancy approv’d him incomparable for the other. John Dryden (1700) http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/special/authors/dryden/dry-intr.html Sir Walter Scott (1808), from his Works of John Dryden: With Chaucer, Dryden’s task was more easy than with Boccacio [sic]. Barrenness was not the fault of the Father of English poetry; and amid the profusion of images which he presented, his imitator had only the task of rejecting or selecting.… Dryden has judiciously omitted or softened some degrading and some disgusting circumstances; as the “cook scalded in spite of his long ladle,” the “swine devouring the cradled infant,” the “pick-purse,” and other circumstances too grotesque or ludicrous, to harmonize with the dreadful group around them. Some points, also, of sublimity, have escaped the modern poet.… In the dialogue, or argumentative parts of the poem, Dryden has frequently improved on his original, while he falls something short of him in simple description, or in pathetic effect. E.Talbot Donaldson http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/canttales/gp/pilgrim.html Appendices Appendix 1: A Note on Chaucer as “The Father of English Literature” After the Norman Conquest (1066), French displaced English as the language of the nobility; Latin was the common language of the educated. There was no standard way of speaking or writing English, and regional dialects differed greatly. During the fourteenth century, this situation began to change. But Chaucer’s decision to write The Canterbury Tales in English was not inevitable. Chaucer’s literary excellence and poetic innovations helped make the case for English as a language in which great literature could be written. For these reasons, he has sometimes been called “the father of English poetry.” Though the title may somewhat overstate Chaucer’s contribution, there is no doubt that he played a crucial role in the history of both English literature and the English language. Appendix 2: Some Notes on Medieval Theories of Humanity and the Cosmos Chaucer’s frequent allusions to medieval science and theology initially frustrate many modern readers. Explaining the concepts outlined below should provide help, not only in basic comprehension but also in contextualizing The Canterbury Tales as part of medieval culture. The Four Humors Medieval medicine, following the ancient Greek authorities like Hippocrates and Galen, believed that the health of the human body and psyche were governed by four bodily fluids, each associated with one of the four elements, certain physical ailments, and with a certain personality type: Bodily Fluid Blood Element Air Phlegm Yellow Bile Black Bile Water Fire Earth Characteristics Courageous, optimistic, amorous Calm, rational Quick-tempered Depressive, pensive Designation Sanguine Phlegmatic Choleric Melancholy If one of the four fluids predominated, it caused physical and personality imbalances. Chaucer sometimes alludes to this theory to describe characters. For example, the Reeve is described as choleric and Chauntecleer as sanguine. The Zodiac Astronomy and astrology were not differentiated during the medieval period: the zodiac was an indication of the connections between humanity and the rest of God’s creation. The constellations were used to situate people in time and space, as well as to explain their personalities. The General Prologue opens with a description of the spring sun passing through Aries (“the Ram”), and the Wife of Bath explains that both Mars (warlike) and Venus (lustful) were in her star chart. Chaucer was evidently knowledgeable about astronomy: he wrote a treatise on the operation of the astrolabe, an early astronomical instrument. The Wheel of Fortune Before it was a game show, the Wheel of Fortune was an important philosophical concept. Expressing the idea that good and bad fortune follow one another in a continual cycle, the Wheel of Fortune is a concept frequently referred to in pagan Classical texts. It was picked up and modified by Christian philosophers during the medieval period, particularly via The Consolation of Philosophy, an influential text by Boethius that Chaucer translated. The concept underlies the genre of medieval tragedy, a type of literature recounting the downfalls of famous people and exemplified by The Monk’s Tale (not anthologized here). It is also relevant to the conclusion of The Knight’s Tale and it is frequently alluded to elsewhere in the tales. Appendix 3: A Brief Summary of The Canterbury Tales One April late in the fourteenth century, thirty pilgrims gather in a London tavern to begin traveling to the shrine of St. Thomas à Becket in Canterbury. Their Host proposes to serve as the judge of a story-telling contest to keep them amused. The pilgrims agree, and once they are underway, The Host asks them to draw lots. The first lot falls (probably not by chance) to the Knight, who tells a romantic tale with epic roots. Though the Host tries to continue in an orderly manner, the drunken Miller upsets his plans. His bawdy tale (fabliau) enrages the Reeve, who suspects he has been mocked and tells a retaliatory tale. The Cook then begins another, incomplete, fabliau which might have been even more shocking than the first two. This ends what scholars call the First Fragment. In the Second Fragment, the Host struggles to establish a more dignified tone by choosing the Man of Law to speak next. The lawyer tells the story of Constance, a longsuffering queen. Trying to continue this edifying trend, the Host invites the Parson to speak, but he is interrupted by the boisterous Shipman. The Third Fragment begins with the Wife of Bath’s rejoinder to the Man of Law’s tale of impossible virtue. In her story, the Wife of Bath satirizes friars because the Friar interrupted her; he, in turn, attacks the Summoner. The Summoner returns the favor by satirizing friars again. In the Fourth Fragment, the Clerk returns to the topic of patient wives with the story of Griselda and her cruel husband. But the Merchant insists that women can also be cruel and tells a fabliau about an old knight with a conniving young wife. The Host begins the Fifth Fragment by inviting the Squire to tell a love story. He obliges with an exotic tale of wonder. The Franklin interrupts the young man’s exuberant but naïve effort to tell another romantic tale of magic, taken from Celtic sources (a Breton lai). The Sixth Fragment opens with the Physician’s story of Virginia, who was killed by her father to protect her honor. Hoping for something less grim, the Host invites the corrupt Pardoner to speak. But the Pardoner upsets expectations by telling an admonitory story about greedy Rioters who seek gold but find Death. When the Pardoner then tries to sell fake saints’ relics to the pilgrims, the Host is furious at his blatant hypocrisy and must be physically restrained from attacking him. The Shipman begins the Seventh Fragment with a fabliau about a merchant and his wife; this is followed by the Prioress’s anti-Semitic tale of a young boy’s murder. The Host then asks Chaucer to speak, prompting the dreadful Tale of Sir Thopas. It is so awful that the Host interrupts to demand something else, so Chaucer obligingly tells the moralistic Tale of Melibee instead. The Host asks the Monk to take his turn, and is rewarded with a string of medieval tragedies: short, pious narratives about the downfalls of famous people. This is so depressing that the Knight interrupts, and the Host teasingly suggests that the Monk tell a hunting tale instead. When he refuses, the Host asks the Nun’s Priest to begin. The result is a delightful beast fable set in a farmyard. The Eighth Fragment begins with the Second Nun’s legend of St. Cecilia. As this tale ends, the pilgrims are interrupted by the sudden appearance of two riders: a Canon (a type of priest) and his yeoman (servant). The Canon rides away in shame after his companion reveals that he is an alchemist, and the Canon’s Yeoman then tells a story about an unscrupulous person who sounds a lot like his master. In a comic exchange with the Host and the Manciple, the drunken Cook falls off his horse. Once the tipsy man has been righted, the Manciple explains how crows became black. This ends the Ninth Fragment. As the pilgrims approach Canterbury, the Host asks the Parson to “knit up” what has come before. The Parson replies that he will not tell a fiction, but rather edifying true stories, and proceeds to deliver a long tract on the necessity of contrition and penance. Appropriately, but disappointingly to most modern readers, Chaucer ends the Tenth Fragment with his Retraction, in which he asks God and his fellow Christians to forgive him for his fictional works, and remember him instead for his religious writings. Appendix 4: Expanded Summary of Anthologized Canterbury Tales Texts General Prologue The narrator (Chaucer the Pilgrim) sets the stage, explaining that people want to make pilgrimages when spring arrives. Preparing to travel to the shrine of St. Thomas à Becket in Canterbury, Chaucer rents a room at the Tabard Inn, near London. That night, 29 other pilgrims check in. Chaucer chats with them, and they invite him to join them. The narrator describes each of the other travelers in turn. The Host proposes a story-telling contest to keep them entertained and volunteers to serve as judge. The pilgrims agree and set out the next morning. Once underway, they choose lots. The Knight wins and begins his tale. The Knight’s Tale Theseus returns to Athens from campaigns in Scythia, where he conquered the Amazons and married their queen, Hippolyta. On the way, he encounters women from Thebes, where King Creon killed their husbands and refuses to bury them. Angered by this injustice, Theseus attacks and defeats Creon. After the battle, two young Theban cousins named Arcite and Palamon are left alive. Because they are royals, they are imprisoned in a tower. Arcite see and fall in love with her. Formerly best friends, they become bitter rivals. Eventually, a mutual friend of Theseus and Arcite pleads for the younger man’s release. Theseus agrees, but exiles Arcite from Athens. Hearing this, Arcite and Palamon debate who is more unfortunate: Arcite, because he won’t be able to see Emilie, or Palamon, because Arcite may raise an army and capture her. Arcite goes to Thebes, where his appearance changes from lovesickness. One night, the god Mercury tells him to disguise himself and find employment in Emilie’s household. Calling himself Philostrate, Arcite soon distinguishes himself and becomes a squire to Theseus. After seven years, Palamon breaks free and heads for Athens. The next day, Arcite unknowingly surprises Palamon, who hides in a bush. But when Arcite complains about his fate as a disappointed lover, Palamon recognizes him, comes out of hiding, and challenges him. The next morning, the cousins meet for a duel, but Theseus, who is out hunting, sees them fighting and intervenes. Palamon reveals both his and Arcite’s identity, and Theseus condemns them to death for disobeying his ban against duels. Hippolyta and Emilie plead on behalf of the two knights, so Theseus forgives them, decreeing they must fight for Emilie at a tournament. The cousins return to Thebes to prepare, and Theseus builds an elaborate arena, including temples to Mars, Venus, and Diana. As the contest approaches, Palamon and Arcite return with their armies. The next morning, Palamon prays at the temple of Venus and Arcite visits the temple of Mars. Because both gods grant their devotees’ requests, they begin quarreling, but Saturn says he’ll find a way around the dilemma. Meanwhile, Emilie begs Diana to let her remain a virgin; her request is denied. At the tournament, Palamon is defeated, but as Arcite takes his victory lap, Saturn has a Fury attack him. When it becomes clear that Arcite’s wound is mortal, he sends for Emilie and Palamon, commends them to each other, and dies. Everyone mourns, but Egeus echoes Arcite’s death-bed speech, saying “This world is but a thoroughfare full of woe / And we are pilgrims, passing to and fro.” A great tomb is built for Arcite and funeral rites are performed in his honor. After several years, Theseus calls a parliament, where he instructs Emilie and Palamon to end their mourning and get married. They live happily ever after. The Miller’s Prologue and Tale The Host praises the Knight’s tale and invites the Monk to speak, but the drunken Miller interrupts. He says he will tell a tale to requite the Knight’s involving a carpenter and his wife. The Reeve, a carpenter, objects unsuccessfully. Chaucer says the tale is offensive, but protests that he has to record each story accurately. He encourages squeamish readers to skip ahead. The tale is set in the Oxford household of a carpenter named John, which contains his 18year-old wife Alison and “Handy” Nicholas, a sly Don Juan and astronomy student living there as a boarder. One day, while John’s away, Nicholas flirts with Alison, finally grasping her by the “queynte” and saying he must have her or die. Alison eventually gives in, and Nicholas says he will come up with a plan to consummate their affair. One day, Alison goes to church, where she is spotted by Absolon, a dandyish parish clerk. He begins serenading her at night, sending her presents, and even offering her money. Alison is not interested. When John goes out of town again, Nicholas carries several days’ supplies to his room. When John returns and two days pass without sight of his boarder, he sends his servant, Robin, to see what’s going on. Peeping through a hole, Robin sees Nicholas staring vacantly at the ceiling. John, convinced that Nicholas has lost his mind, sends Robin to heave the door from its hinges. John goes in to “awaken” Nicholas, who says God is sending a Second Flood. He instructs John to find three tubs, put food in them, and hang them in the rafters so Nicholas, John, and Alison can punch a hole in the roof and sail away once the flood begins. On the appointed evening, Nicholas, John, and Alison climb into the tubs. When John starts snoring, the two lovers creep down the ladders and into bed. Absolon interrupts them with a serenade and Alison tells him to go away, but he begs for a parting kiss. Exasperated, she sticks her rear out the window. Absolon kisses her heartily, but realizes something is wrong, because “a woman has no beard.” While Alison and Nicholas laugh at him, Absolon frantically swipes his lips and heads to the blacksmith’s to borrow a hot coulter. He returns and tells Alison he’ll give her a gold ring if she kisses him properly. This time, Nicholas dangles his hindquarters out the window. When Absolon asks for a sign, Nicholas gives a tremendous fart. Absolon brands Nicholas’s rump with the coulter. Nicholas howls for water. John, thinking the flood’s begun, cuts himself down from the ceiling and falls with a crash. Nicholas and Alison call for help and explain to the neighbors that John injured himself because of delusions about a Second Flood. Everyone laughs at John, and the lovers get away with their scam. The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale The Wife of Bath (Alison) praises the value of experience and says she’s had five husbands. She notes that Old Testament patriarchs had several wives and that St. Paul only recommended virginity. She also says Paul’s writings give her authority over her husband. The Pardoner interrupts, saying he has been warned off of marriage by Alison’s comments. She tells him to wait and listen to learn more. After pleading with the other pilgrims not to take offense at her frankness, Alison says she’s had three good husbands followed by two bad ones: the first three were old men she could easily control. The next two were younger and willful: her fourth husband had a mistress, and, though she dearly loved her fifth husband, an Oxford student named Jankyn, he caused her great pain. Alison began pursuing Jankyn while her fourth husband was alive. Enamored of the 20year-old clerk, 40-year-old Alison gave control of her property to him once they married, but soon regretted it when her new husband entertained himself by reading sexist commentary aloud. One day, Alison tore Jankyn’s book, and he struck her so hard she was permanently deafened. Faking mortal injury, she lured Jankyn closer and hit him back. Eventually, they were reconciled, and Alison regained control. Alison says she’ll begin her tale. The Friar laughs, saying her preamble was certainly long enough. The Summoner sarcastically notes that friars always butt in when they’re not wanted. Angry, the Friar promises to tell a tale against summoners. The Summoner retorts that he’ll tell one against friars. The Host interrupts and asks Alison to continue. Alison sets the scene in Arthurian times, which she says were full of fairy-magic. She says fairies and elves have been replaced by friars and mockingly suggests that women now fear being raped by friars, rather than being abducted by fairies. Beginning in earnest, Alison speaks about a knight of Arthur’s court who rapes a maiden. Arthur condemns the knight to death, but the queen asks permission to pronounce a different sentence. When Arthur agrees, she says the knight can save himself by discovering “what women most desire” within a year and a day. The knight gets a different response from everyone he asks. At year’s end, he rides despairingly toward Arthur’s court. In a forest, he sees a group of dancing ladies, but when he draws closer, he finds only an ugly old woman (the Loathly Lady). The Loathly Lady asks what he seeks, and he tells her. She says she’ll help if he consents to do whatever she asks. Desperate, he agrees. On the appointed day, the knight gives the queen and her jury the Loathly Lady’s answer: that women most desire sovereignty. When they agree this is true, the Loathly Lady demands that the knight marry her. The knight tries to buy her off, but the Loathly Lady refuses. After a hasty wedding, the woeful knight joins his bride in bed. When the knight turns from her, the Loathly Lady objects. In an outburst, the knight says he’ll never be happy, since his wife is ugly, old, and low-born. Quoting many authorities, the Loathly Lady explains that noble blood doesn’t confer nobility of character, that older people deserve respect, and that an ugly wife is less likely to cheat. She then asks the knight whether he’d rather have her as she is and faithful or young and beautiful but unfaithful. Humbled, the knight says he’ll do as she recommends. Happily, the Loathly Lady tells the knight she’ll be both beautiful and faithful and invites him to look at her. When he does, he finds that she’s gorgeous. They live happily ever after. Alison concludes with a prayer for young, frisky, pliant husbands and the strength to outlive them, as well as a curse on troublesome, miserly ones. The Merchant’s Prologue, Tale, and Epilogue The Merchant says he’s only been married two months, but already knows that few wives are good ones. The Host asks him to tell a tale, and he consents. An old knight named January marries a beautiful young woman named May. January’s squire, Damian, falls in love with her at the wedding feast and becomes sick with longing. Eventually, January notices Damian’s absence and sends May to check on him. Damian confesses his feelings by passing her a note, and she writes an encouraging reply. January keeps a walled garden with a locked gate, but May and Damian copy the key. One day, January (now blind) wants to walk in the garden, and May signals for Damian to join them and climb into a pear tree. Pretending that she craves fruit, May convinces January to help her into the tree. May and Damian immediately start having sex in the tree. The god Pluto, angry at such disloyalty, gives January his sight, but Pluto’s wife, Persephone, immediately gives May the ability to explain herself: she’s been told that there is no better cure for a husband’s blindness than for his wife to “struggle” in a tree with another man. January is appeased. In the epilogue, the Host bewails his fate as a husband. The Franklin’s Prologue and Tale The Franklin tells the story of Arveragus, a Breton knight, and his wife Dorigen. While Averagus is away, his squire, Aurelius, approaches Dorigen and confesses his love for her. She jokingly says she won’t sleep with him unless he clears the coastline of the rocks that threaten her husband’s boats. Aurelius’s brother introduces him to a magician who’ll accomplish this task for a large sum. When the deed is done, Aurelius again approaches Dorigen, who is grief-stricken: she is now honor-bound to cheat on her husband. Dorigen tells Arveragus what happened, and he says Dorigen must honor her oath. Impressed by the couple’s behavior, Aurelius frees Dorigen from her obligation. When the magician hears this, he returns Aurelius’s money. The Franklin closes his tale by asking who was most generous. The Pardoner’s Introduction, Prologue, and Tale The Host says he needs a drink or merry tale and asks the Pardoner to speak. Several pilgrims beg the Pardoner not to tell “ribaldry”; he says he’ll do his best. In his prologue, the Pardoner admits to making a living by selling fake saints’ relics to people after intimidating them with sermons about the evils of greed. He acknowledges he’s a “vicious” man, but says he’s also an excellent preacher who sometimes does people’s souls good. The Pardoner’s tale is about three rioters (partiers) in Flanders, who curse, drink, and eat excessively. One day, while drinking in a tavern, they see a man taking a body to the graveyard. They learn that the corpse is that of a friend who was stabbed in the back by Death. Angry, the rioters swear to find and kill Death. Setting out, they come across a very old man who wishes Death would take his life and Mother Earth would let him in. The rioters roughly order this man to give them information about Death’s whereabouts; he says he last saw Death under a nearby tree. The rioters go to the tree and find eight bushels of gold. Thrilled, they forget their search for Death and instead argue about who should go for provisions so they can guard the treasure. Finally, they draw straws to decide. When the youngest man loses and heads for town, the other two plot to kill him so they can keep his share of the gold. Meanwhile, the youngster puts poison in the wine he buys for them. When he returns, his companions kill him, but then drink the wine and die immediately. They’ve managed to find Death after all. The Pardoner closes with a warning against avarice and offers to let his fellow pilgrims kiss his relics and buy pardons, in case they should fall from their horses and die. He says the Host should go first, because he’s the most sinful. Infuriated, the Host says he wishes he could cut off the Pardoner’s testicles and “enshrine” them in a hog’s turd. The Knight steps in to reconcile the two men, forcing them to kiss as a token of friendship. The Prioress’s Prologue and Tale The Prioress begins with a prayer to God and the Virgin Mary, then tells the story of a widow’s son, a little clergeon (schoolboy) living in Asia. He learns a Marian hymn, which he sings every day as he walks to school through a Jewish ghetto. Angered by this, the Jews hire an assassin to cut the child’s throat. Anxious when her son doesn’t return, the widow looks for him. When she passes the latrine where he lies, the little clergeon’s corpse miraculously begins singing. The child’s body is taken to an abbot. When he asks what happened, the corpse explains that the Virgin Mary animated him and will take his soul to Heaven if a magic grain she placed on his tongue is removed. The abbot does this and the people build a tomb for the boy. The Jews are condemned to a violent death. The Prioress closes with a prayer to St. Hugh of Lincoln. The Nun’s Priest’s Prologue, Tale, and Epilogue After hearing sixteen doleful tragedies from the Monk, the Knight interrupts to ask for something more cheerful. When the Monk refuses, the Host asks the Nun’s Priest to begin. The tale opens with a description of a poor widow, who lives in a cottage with her two daughters. She has pigs, cows, a sheep, and a gorgeous rooster named Chauntecleer, whose harem of seven hens includes the beautiful Pertelote. One morning, Chauntecleer groans in his sleep, and Pertelote awakens him. Chauntecleer says he had a dream in which a dog-like creature stalked him. Pertelote accuses him of cowardice, insisting that dreams result from poor health, and advises him to take a laxative. Chauntecleer disagrees, giving learned examples of dreams as premonitions. He says he sets no store by laxatives and sweet-talks Pertelote into complacency. Chauntecleer happily lords it over the farmyard, but a fox named Russell lurks among the cabbages. When Chauntecleer finally notices this, he prepares to flee, but Russell says he only wants to hear Chauntecleer sing. When the proud bird rises onto his toes, closes his eyes, and stretches out his neck to begin, Russell rushes forward, grabs him by the neck, and drags him toward the woods. The hens shriek. When the widow and her daughters realize what’s happened, they shout and chase after Russell. They’re joined by neighbors, several dogs, and the spooked cows and pigs; frightened ducks, geese, and bees add to the ruckus. Chauntecleer, speaking as one noble to another, tells Russell that, if he were in his position, he’d order the unseemly rabble to leave. When Russell opens his mouth to agree, Chauntecleer breaks free and flies into a tree. Russell tries flattery again, but Chauntecleer’s learned his lesson. Russell slinks away without dinner, noting that only fools chatter when they should be silent. The Host praises the tale and notes that the Nun’s Priest is so good-looking that he’d make a fine “rooster” himself if he weren’t in holy orders. Chaucer’s Retraction Chaucer asks his readers and God to forgive him for writing poems about “worldly vanities” and thanks God for allowing him to write and translate Christian poems and tales. He prays for the ability to repent and do enough penance to obtain salvation. Appendix 5: Ideas for Classroom Exercises The panoply of characters and the array of professions often lead to difficulties for students. One fun and useful way of helping first-time Chaucerians better distinguish and understand the personalities of the pilgrims is to split the class up into small groups and ask each cluster of students to write a “personal ad” for one or more of the characters. This short assignment should include both a description of the pilgrim in question and a description of what that person is “in search of.” You might even excerpt a few personal ads from a local newspaper, together with a “key” for the acronyms and abbreviations often used in such ads. Once the ads are completed, collect and read them aloud, asking the entire class to comment. In addition to aiding comprehension, this exercise may provide fodder for discussing the concept of generic rules and conventions and what is entailed in writing to or against them. Another way of jump-starting discussions about the pilgrims is to play a game of “Would you rather,” using modern, everyday situations to help students gain a clearer sense of the characters’ respective personalities. To do this, write up a short, ungraded “quiz” composed of questions such as, “Would you rather go to a bar with the Wife of Bath or the Miller?” and “Would you rather buy a car from the Pardoner or the Host?” Once the students have completed this assignment, collect the results and tally them on the board. The results should provide plenty of material for discussion as students explain and debate their choices. In order to help students better understand medieval manuscript culture and Chaucer’s place in it, refer to the illustrations from the Ellesmere manuscript accompanying each tale. You may also consider bringing in color photos or facsimiles of one or more Canterbury Tales manuscript pages (in color, whenever possible). Ask the students to analyze the page(s) as a physical artifact. How is the text laid out? Are there illuminations? If so, how painstaking are they and what message do they seem to convey? What is the script like in which the text is written? How readable is it? How carefully was the scribe drawing it? What are the margins like? Are there any indications as to how the text was used by its readers (notes, signs of wear, etc.)? Once the students have described the page(s), you may want to ask more general questions concerning what these examples might say about medieval scholars’ ideas of Chaucer. How would your students have laid out the page if they were making their own Chaucer manuscript, and why? Understanding The Canterbury Tales’ place in medieval oral culture also can give students a helpful idea of how the tales’ first witnesses encountered them. Depending upon the needs of your student, the aims of your course, and the time available to you, you may wish to ask students to listen to the readings in the “Sounds of British Literature” section of the anthology’s website, and then to memorize and recite a set number of lines with Middle English pronunciation. You may also, of course, perform sections of the text yourself, or listen to recordings of key sections together. To aid comprehension in the latter two cases, you might allow students to read along while listening and then ask them to listen without looking at the text. Any of these options should provide you with good opportunities for discussing the differences between textual and oral presentation, the rhythms and other sound patterns of Chaucer’s poetry, and how audience response might change the experience of encountering Chaucer’s work. In order to help students make connections among the tales, you might try focusing on particular concepts as “bridges.” Begin by writing significant Chaucerian themes, words, or phrases on index cards before your class meeting. In class, split the students up into small groups and ask them to (a) connect at least two of the tales using the content of their index cards and (b) point out at least one similarity and one difference in the way that concept works in each tale. Students should cite specific passages to support their claims. Ask each group to present their insights in turn, allowing other students to pose questions and offer comments. In order to improve comprehension, help students understand the value of reading Chaucer in Middle English, and provide a sense of the many possibilities for translation and interpretation, consider asking your class to translate a short section of text with the aid of the online Middle English Dictionary (see Appendix 6 for web address). Comparing the students’ work together in class and discussing the reasoning behind their interpretations should offer illuminating results. Appendix 6: Some Helpful Resources for Teaching The Canterbury Tales Books Ashton, Gail and Louise Sylvester. Teaching Chaucer. Teaching the New English Series. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. 2007. Boitani, Piero and Jill Mann. The Cambridge Companion to Chaucer, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Cooper, Helen. Oxford Guides to Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1996. Ellis, Steve, ed. Chaucer: An Oxford Guide. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005. Gibaldi, Joseph and Florence H. Ridley, eds. Approaches to Teaching Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Approaches to Teaching World Literature. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1980. (A new edition of this work is currently in preparation.) Hallissy, Margaret. A Companion to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1995. Saunders, Corinne. Chaucer. Blackwell Guides to Criticism. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2001. General Online Resources Baragona, Alan. Baragona’s Chaucer Page http://academics.vmi.edu/english/chaucer.html. “Chaucer, Geoffrey,” pseud. Geoffrey Chaucer Hath a Blog. http://houseoffame.blogspot.com/. Duncan, Edwin. “A Basic Chaucer Glossary.” http://pages.towson.edu/duncan/glossary.html. Halsall, Paul. The Internet Medieval Sourcebook. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/sbook.html. Irvine, Martin and Barbara Everhart, eds. Labyrinth: Sources for Medieval Studies. http://www8.georgetown.edu/departments/medieval/labyrinth/ Kline, Daniel T. The Electronic Canterbury Tales. http://www.kankedort.net/. NeCastro, Gerard, ed. eChaucer: Chaucer in the 21st Century. http://www.umm.maine.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer/index.htm Pearsall, Derek. “Thirty-Year Working Bibliography of Chaucer and Middle English Literature: 1970-2000.” http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/bibliography/b-1-intr.htm Peck, Russell A. TEAMS Middle English Texts. http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/tmsbsg.htm Regents of the University of Michigan. Middle English Dictionary. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/med/. Wilson-Okamura, David, ed. “Teaching Chaucer.” http://geoffreychaucer.org/teaching/. Wittig, Joseph, ed. The Chaucer Metapage. http://www.unc.edu/depts/chaucer/. Online Image Resources Chaucer’s Portrait from the Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript. Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:ChaucerPortraitEllesmereMs.jpg Duncan, Edwin. “Images.” http://pages.towson.edu/duncan/chaucer/images.htm Hooper, William. Woodcuts of the Ellesmere portraits of the Canterbury pilgrims. 1868. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/canttales/woodcuts/woodcuts.htm Huntington Library Staff. Images from the Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript. http://www.huntington.org/LibraryDiv/ChaucerPict.html and http://www.huntington.org/HLPress/images/chaucer2b.jpg. Queen’s University Library Staff. “Pages from the Kelmscott Chaucer.” http://library.queensu.ca/webmus/sc/images/kelmscott_chaucer-larger.jp Snelling, Joanna, ed. “Corpus Christi College MS. 198.” Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. http://image.ox.ac.uk/show?collection=corpus&manuscript=ms198. Symons, Dana. “Chaucer Reading Troilus and Criseyde Aloud.” Medieval and Renaissance Literature in Britain. http://courses.ats.rochester.edu/hahn/ENG206/50CCCCTroilus1.jpg University of Arizona Library Special Collections Staff. High-resolution image from the Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript. http://www.library.arizona.edu/exhibits/illuman/images/full_resolution/14_02.jpg. Audio Resources (in addition to the “Sounds of British Literature” section of the Broadview Anthology website) Baragona, Alan. “The Criying and the Soun: The Chaucer Metapage Audio Files.” The Chaucer Metapage. http://academics.vmi.edu/english/audio/Audio_Index.html. Benson, L. D. “Teach Yourself to Read Chaucer’s Middle English.” The Geoffrey Chaucer Website. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/less-0.htm. “Chaucer’s Pronunciation, Grammar, and Vocabulary.” The Geoffrey Chaucer Site. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/pronunciation/ The Chaucer Studio. Catalog of recordings available online at http://english.byu.edu/Chaucer/. The publisher gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Andrea F. Jones of the University of California, Los Angeles for the preparation of the draft material.