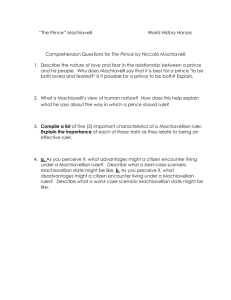

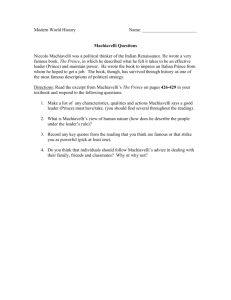

New Monarchs Practice Essay Feedback

advertisement

New Monarchs Practice Essay Feedback Essay Organization I mentioned that you can have 2-3 supporting points, but read carefully: So with the case of this essay, you can organize the essay in one of two ways: (1) by countries or (2) by monarchs’ actions/traits. If you organize the essay by country, then you can have 2 body paragraphs because the essay prompt says you only need to discuss 2 countries. You could write a third paragraph on a third country, but this is unnecessary and may not earn you any more points if your other 2 paragraphs are weaker as a result. If, however, you organize the essay by monarchs’ actions, then you must have 3 body paragraphs, as I can think of well more than 3 potential topics and the essay prompt does not dictate how many actions to discuss. How much data?? A number of you organized the essay by country and then provided just one data point for each country (ex. writing a paragraph on England, you discussed the Court of Star Chamber only). This is insufficient. If you organized the essay by country, then you should have discussed multiple actions by the monarch(s) in that country. Given how much we know about these monarchs from the textbook, I’d say you could probably discuss 3 actions in each paragraph. If you organized the essay by new monarchs’ actions,/traits then you should use examples from at least 2 countries in each body paragraph. Unlike in your English classes, where your teacher tells you to use 2 quotations per body paragraph, Warrants The strongest essays connect the new monarchs’ actions to The Prince very explicitly and thoroughly. They tend to use phrases like, “Like Machiavelli wrote in The Prince …”, etc. Quite a lot of you sought to define new monarchs’ actions as “cunning,” “ruthless,” etc. Some of you did this well, but many of you need to be careful here. I often don’t find such arguments to be very convincing because (1) determining that an action is “cunning” can be subjective (ex. is there a hint of evil in the action, as “cunning” could imply, or does the action just represent good sense?), (2) these arguments usually did not provide sufficient analysis to make me understand why the action is “cunning,” and (3) I want to know what the end goal was. While I encouraged you to choose your own definition of “Machiavellian,” and still do, you need to go beyond just saying that a Machiavellian ruler is ruthless. You can make that case, but you need to extend it. Why is he/she ruthless? Does Machiavelli advocate that a ruler employ cruelty for kicks and giggles? Is he simply a sadist? (well, maybe, but then you need to say so … and I will look forward to reading a good case for it!). Another, perhaps more convincing, way to analyze new monarchs’ actions is to compare them to specific advice that Machiavelli gave in The Prince. For example: relating the methods that new monarchs used to undercut noble power, such as the Court of Star Chamber, appointing less powerful people to the royal council, etc., to Machiavelli’s advice that a prince should ensure that he has no rivals for power. Other bits The Prince is not a novel. Novels are fictional. The Prince is nonfiction, and you might call it a guide, book on political theory, work, etc. Do not make arguments based on “If” statements. This is what we call the counter-factual, as you are posing some scenario opposite of the facts. For example, “If Ferdinand and Isabella did not use Machiavellian rule, they probably wouldn’t have had much control over Spain or be able to reach the goal of uniting the Iberian Peninsula.” You cannot know what might have happened under different circumstances, so stick to analyzing what did actually happen. It is fine and good to acknowledge data that doesn’t support your argument. For example, in writing about England, you might acknowledge that Henry VII avoided war, whereas Machiavelli spent many chapters advising a prince to study war and build a good army. You would then go on to explain how even though the king did not follow every piece of advice in The Prince, he did so sufficiently to be worthy of the label “Machiavellian” (and you would provide plenty of data and warrant to justify that claim). And a model body paragraph and conclusion for you to read: The new monarchs were Machiavellian because of their wariness to allow nobles to have authority. The English king Henry’s royal council was the center of national power, and he made clear his distrust of the nobility. Very few nobles were chosen to be the king’s advisors. Instead, small landowners and urban residents who were educated in law made up the council. Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain also excluded high ranking lords from their royal council, choosing lesser landlords for the position. Therefore, the influence of the nobility was greatly reduced. Machiavelli states that a prince should avoid appointing nobles as his advisors. Nobles have their own subjects and feel no real loyalty to the prince, so if they are discontent, they will revolt. Henry, Ferdinand, and Isabella’s distrust of the nobility agreed with Machiavelli’s ideas. These rulers excluded the nobles from their most powerful councils, so the main power would still remain in their hands. They chose people of the middle class to be advisors, so they would win favor with the people. This way, if the nobles did become unhappy and revolt, they would not have the support from the subjects, and their uprising would fall apart. These rulers crushed all opposition, just as Machiavelli said a prince must do to remain in power. King Henry, King Ferdinand, and Queen Isabella were Machiavellian in practice because of their disbelief in allowing nobles to gain power. During the 15th and 16th centuries, the new monarchs of Europe practiced Machiavellian tactics because they mistrusted nobles, preferred to be feared than loved, and strived to appear virtuous to their subject. The Black Death and the Hundred Years’ War left Western Europe depopulated, economically ruined, and agriculturally feeble. Leaders could not rule effectively and problems remained unsolved. However, beginning in the 15th century, rulers began to act upon Renaissance political ideas and rebuild their governments, thus beginning the age of the “new monarchies.”