are plant breeder's rights outdated? a

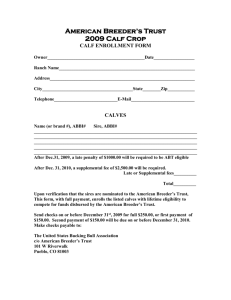

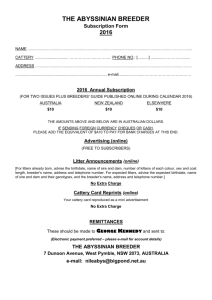

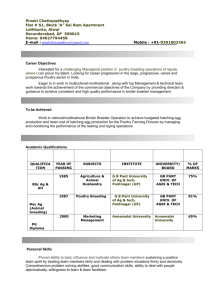

advertisement