THE NEW FUTURE Global Brands What do KFC and Pizza

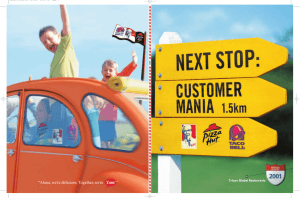

advertisement

THE NEW FUTURE Global Brands What do KFC and Pizza Hut conjure up abroad? Are they American symbols? Or have they become global brands? Tricon, the company that owns both chains, has placed a huge bet that it's the latter. FORTUNE By Brian OKeefe In early October, on the first Muslim holy day after American warplanes began the bombing campaign in Afghanistan, thousands of protesters spilled out onto the streets of Karachi. Armed with sticks and bats, intermittently chanting "Death to America," they made their way through the streets of Pakistan's largest city, smashing windows and setting fire to a bus and several cars along the way. The mob's objective was the U.S. consulate. But police barricades and tear gas turned them back. So they went looking for the next-best option: Colonel Sanders. To the demonstrators, it didn't matter that the nearby KFC, one of 18 in Pakistan, was locally owned. The red, white, and blue KFC logo was justification enough. Though the owners of the restaurant had tried to cover the KFC signs in an attempt to protect their property, their effort was futile; the protesters set fire to the restaurant before being dispersed by police. "You have no choice but to operate in a world shaped by globalization," Andy Grove wrote in FORTUNE in 1995. "Adapt or die." That maxim is truer today than ever, especially for companies like Coke, McDonald's, Gillette, and Kodak, companies that own the great, ubiquitous--but aging--American brands. Tricon Global Restaurants, which owns not only KFC but also Pizza Hut and Taco Bell, is another good example. For companies like these, growth in the U.S. is now measured in the low single digits--at best. So if they want to grow, they will have to go global. As, indeed, they have. Look no further than KFC. Founded 50 years ago as Kentucky Fried Chicken by the late Colonel Harland Sanders, the chain has around 5,000 U.S. restaurants--and 6,000 abroad. It has 158 franchises in Indonesia, which has the world's largest Muslim population. (Three were also looted in the days after Sept. 11.) It has a restaurant in the holy city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia. In all, KFC has stores in more than 80 countries, including Japan, Australia, Egypt, Mexico, Malaysia, and Swaziland. In China, where KFC has more than 500 restaurants, Tricon is opening, on average, ten new stores a month. And it's not about to slow down, Sept. 11 or no. Just days after the Karachi incident, Tricon CEO David Novak reaffirmed to Wall Street analysts that overseas growth would continue unabated--and downplayed the potential impact of an anti-American backlash. As Novak sees it, the company's long-standing presence in so many countries makes it an accepted part of the landscape, and therefore less likely to be a major target. "We're going to have some radical situations," he told Fortune, "but not to the extent that we think it's 1 going to alter our business plan." Then again, what choice does he have? As with so many U.S. companies, continued globalization is, quite simply, the key to Tricon's future. Tricon was born in 1997, when PepsiCo decided to spin off its restaurant division and refocus on its core beverage business. Prior to the spinoff, the fast-food business--which included the three chains Tricon now owns--had been a laggard; the assumption was that an executive team focused solely on restaurants would get better results. And it has. Margins are up--from 11.6% to just over 15%. Revenues ($7.1 billion in 2000) and profits ($860 million) have grown steadily. The stock (the symbol is YUM) took some hits last year but has rebounded nicely, doubling since August 2000. Clearly those good things have come about in large part because Tricon is committed to international growth. Since it was formed, Tricon has opened more than 5,100 restaurants--of which nearly 3,200 have been abroad. It plans to open more than 1,000 stores a year overseas for the foreseeable future. Indeed, its 30,000-plus outlets in more than 100 countries are the most of any restaurant company in the world. "A lot of people talk about being international, but they don't have the infrastructure to really get it done," says Novak, 49. "We now have the people, the brands, and the presence." Like most successful global companies, Tricon believes that business, like politics, is local. As a practical matter, that means that Tricon can't just open restaurants based on the U.S. model and expect success. It has to adapt to local tastes and negotiate changing cultural and political climates. In Japan, for instance, KFC sells tempura crispy strips. In northern England, KFC stresses gravy and potatoes, while in Thailand it offers fresh rice with soy or sweet chili sauce. In Holland the company makes a potato-and-onion croquette. In France it sells pastries alongside chicken. And in China the chicken gets spicier the farther inland you travel. "Most companies are not really jumping up and down now and saying, We're an American company,"' says Clayton Tolley, CEO of global-branding firm Addison Whitney. "More and more, if it's only an American brand without a regional appeal, it's going to be difficult to market." You can see that quite clearly in England, where Tricon has reestablished itself in a market in which the KFC brand had become stale and tired. Over the previous decade, the growth of the European businesses of Pizza Hut and KFC had slowed dramatically. The novelty of fried chicken as an alternative to fish and chips had long since worn off. Indeed, the company found itself competing in a distinctly Americanized atmosphere. Take, for instance, the KFC at the Teesside Park shopping center outside the industrial town of Middlesbrough in northeastern England. The new KFC shares a parking lot with TGI Friday's and Frankie & Benny's New York Italian Restaurant and Bar. Across the service road are McDonald's and Burger King. KFC's American roots are virtually meaningless. "It was a novelty at first, but it's just another restaurant really," says one woman in her late twenties eating an Original Recipe value meal. "They're all American, aren't they?" Paradoxically, one key to Tricon's revival in England--and its future prospects in the rest of Europe--was the willingness of the corporation to take more control over the 2 franchises. Then again, maybe that's not such a paradox; part of the trick for any large franchise operator is to allow local flexibility while maintaining quality control and a central marketing message. So: Tricon shut down franchisees that didn't meet the company's standards. It introduced new products into the British market, getting away from the old "chicken in a bucket" concept. And it established company-owned restaurants in such countries as France, Holland, and Germany--hoping to demonstrate success and inspire new, ambitious franchisees to join up. In China, on the other hand, the situation feels much different. Indeed, an A.C. Nielsen survey last year found that KFC is the most recognized foreign brand in China, ahead of Coke and McDonald's. The profits for Tricon's Greater China operation (which includes Taiwan and Hong Kong) increased 47% last year. It just opened its 500th KFC restaurant in mainland China in early October. By the end of the year there will be 540 KFCs and 65 Pizza Huts in 130 cities--even though the cost of a KFC value meal is equivalent to about six hours of the average person's salary. "We know that the business in China will be bigger than it is in America someday," says Novak. Some of that success can be attributed to the fact that the company's brands got in early. KFC opened the first fast-food chain in China in 1987, and Pizza Hut was there by 1990. But the real key has been the deft management of Sam Su, who heads up the company's China operation. Although he grew up in Taiwan, Su had never been to China before he arrived in December 1989, just months after the Tiananmen Square demonstrations. At the time, there were only four KFCs in China. Though the government wanted Western investment, it was still wary. Su, 49, a tall, deep-voiced man with a Wharton MBA and a background in engineering, saw great potential but knew that it would be a long process. "From a very early stage I realized that this was going to take my lifetime, and the lifetimes of a lot of other people," he says. 3