Taking action against acute COPD

advertisement

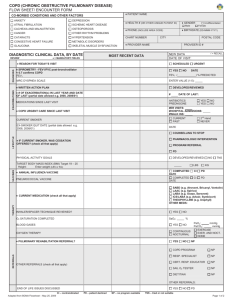

Strictly Clinical — Taking action against acute COPD By Mary Lou Warren, MSN, RN, CNS-CC, CCRN, and Sarah Livesay, BSN, RN MOST NURSES, you’ve Exacerbations are common associated largely with elderly probably cared for many patients populations, it’s increasingly among the 14 million with chronic obstructive pulprevalent among middle-aged Americans with COPD. To monary disease (COPD). This adults. umbrella term denotes a group intervene effectively, you of conditions—emphysema, Risk factors and assessment need up-to-date nursing chronic bronchitis, and in some Cigarette smoking is the leading cases, asthma—associated with COPD risk factor. Other risk facknowledge and expertise. an abnormal inflammatory retors include exposure to occupasponse and severe pulmonary airflow obstruction. The tional and environmental pollutants and childhood rescondition progresses slowly and isn’t fully reversible; piratory infections. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency is the no known cure exists. best documented genetic risk for developing COPD. Many COPD patients experience acute exacerbations This deficiency may predispose some persons to emrequiring emergency treatment and sometimes hospitalphysema and may be a factor in causing emphysema ization. Tracheobronchial infection and air pollution are in people who’ve never used tobacco or who develop the most common causes of exacerbations, but about the illness at an early age. one-third of the time, the cause can’t be identified. General signs and symptoms of COPD include COPD accounts for about 1.5 million emergency decough, excessive mucus production, and shortness of partment visits by adults ages 25 and older. breath on exertion. During exacerbations, fever, puruA thorough understanding of COPD and its treatment lent sputum, increased cough, and increased shortness helps you provide the most effective patient care. Upof breath may occur. (For manifestations specific to to-date knowledge of the disease and appropriate medemphysema or bronchitis, see Comparing emphysema ical treatment and nursing interventions can improve and bronchitis.) patient outcomes and quality of life. This article discusses management of patients who’ve been hospitalized for acute COPD exacerbations. LIKE Comparing emphysema and bronchitis More than 14 million people in the United States have COPD. A leading cause of chronic illness, disability, and death, COPD resulted in 119,000 deaths and 726,000 hospitalizations in 2000. The total cost of the disease was estimated at $32 billion in 2002. COPD is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States and is expected to become the third leading cause by 2020. COPD deaths have been increasing, while deaths from coronary artery disease and stroke have been declining. COPD is now equally prevalent in men and women. Although once 12 American Nurse Today December 2006 Emphysema and bronchitis are the two main forms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A patient may have one or both conditions. In emphysema, alveoli overinflate. As they undergo progressive damage, pockets of dead air called bullae form, impeding exhalation. Signs and symptoms include shortness of breath on exertion and air hunger. Many emphysema patients develop a barrel chest from lung hyperinflation. Bronchitis is marked by inflammation of the tracheobronchial mucous membranes. Abnormal bronchial changes impede bronchial drainage, increasing mucus production. Bronchitis is considered chronic when symptoms last at least 3 consecutive months in at least 2 consecutive years. Acute bronchitis is relatively common in COPD patients. Assessment findings during an acute exacerbation During an acute emphysema or bronchitis exacerbation, expect: • breathlessness • increased sputum • wheezing • change in sputum color • chest tightness • decreased activity tolerance • increased cough • general malaise and fatigue. Photo: National Institutes of Health The vast toll of COPD Treating acute exacerbations For patients hospitalized with acute COPD, treatment may entail behavior therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, medical or surgical interventions, and education. Medical treatment is essential and may involve bronchodilators, inhaled glucocorticoids, oxygen therapy, and antibiotics. Bronchodilators Bronchodilators improve symptoms and functional status in COPD patients. They fall into two broad categories: • beta-agonists, which relax and open the airways by causing smooth-muscle relaxation • anticholinergics, which block acetylcholine (a chemical that normally causes the airways to contract) and decrease mucus production. (See Bronchodilator therapy for COPD patients.) Exacerbations usually necessitate an increased dosage or dosing frequency of the bronchodilator, which may be given every 2 to 3 hours. Beta-agonists and anticholinergics also may be given to increase the bronchodilatory effect. Drug delivery devices vary. To provide education and assess the patient’s ability to self-administer the drug effectively, make sure you’re familiar with the appropriate delivery device. Bronchodilator therapy for COPD patients Signs and Symptoms of Hypoglycemia S For patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchodilator therapy may involve fast- and long-acting beta-agonists or anticholinergics. • Fast-acting agents have a faster onset and shorter duration. When used for symptom control, they must be given every 4 hours. They’re also indicated for “rescue” treatment during an acute episode of shortness of breath or before increased activity. Most come in aerosol form and should be used with a spacer device. • Long-acting agents can be given once or twice daily. They provide better and longer symptom control and greater convenience. Typically, the active ingredient is a powder for inhalation. The COPD treatment plan usually includes a long-acting bronchodilator for symptom control and a short-acting bronchodilator for “rescue” in acute situations. Patients who have acute exacerbations typically are advised to increase the bronchodilator’s dosage or dosing frequency and to combine beta-agonists with anticholinergics for greater effect. This chart lists specific bronchodilating drugs used to treat COPD, along with their uses and corresponding nursing considerations. Drug category Uses and nursing considerations Fast-acting beta-agonists • albuterol • pirbuterol • Uses: to relax and open airways, increase ciliary movement to help clear mucus, and help prevent exercise-induced wheezing; for “rescue” to help stop attacks • Usually are given as two puffs every 4 hours • Should be used with spacer device or in nebulizer (albuterol) Long-acting beta-agonists • formoterol • salmeterol • Uses: to relax and open airways and for long-term control • Available as powder for inhalation • Usually given as one inhalation twice daily Fast-acting anticholinergics • ipratroprium • Uses: to relax and open airways • Should be used with spacer device or in nebulizer Long-acting anticholinergics • tiotroprium • Uses: to relax and open airways and for longterm control • Available as powder for inhalation • Usually given as one inhalation once daily Glucocorticoids Inhaled glucocorticoids are recommended for patients with repeated exacerbations or whose forced expiratory volume1 (FEV1 ) is less than 50% of the predicted value. FEV1 is the volume of air forced out of the lungs in the first second of exhalation after a maximal inspiration. During an exacerbation, glucocorticoids initially may be given I.V. and later switched to the oral form. The dosage must be tapered before discontinuation. Although no standard tapering protocol exists, a treatment course commonly spans 10 to 14 days. Oxygen therapy Long-term oxygen therapy increases survival in COPD patients with chronic respiratory failure. Supplemental oxygen improves hemodynamics, exercise endurance, lung mechanics, and mental status. During an exacerbation, oxygen therapy is adapted to the patient’s condition. Obtain an arterial blood gas sample to evaluate the patient’s arterial oxygenation, carbon dioxide (CO2) level, and acid-base balance. Oxygen delivery must be regulated to avoid increased CO2 levels and acidosis. As the patient stabilizes, measure room air oxygen saturation (O2 Sat) before and after activity. If O2 Sat is below 90% within 48 hours of the planned discharge, the patient’s eligibility for home oxygen therapy should be evaluated. Antibiotic therapy If your patient shows signs of bacterial infection, expect to administer oral or I.V. antibiotics. Signs and December 2006 American Nurse Today 13 symptoms of bacterial infection may include increased dyspnea, sputum production, and sputum purulence. Vaccinations To prevent exacerbations, COPD patients should receive appropriate vaccinations. Administering the influenza vaccine may reduce serious illness and death by nearly 50%. Behavior therapy Behavioral therapy is a key component of COPD treatment. Smoking cessation is the most effective way to prevent COPD or slow its progression. Provide counseling regarding smoking cessation with every hospitalization. Pulmonary rehabilitation Teaching patients how to use a flutter valve A small, hand-held device that helps loosen and expel pulmonary secretions, the flutter valve consists of a small plastic cone housing a steel ball. Exhalation forces the ball upward. When the ball falls back toward the bottom of the device, its movement causes vibrations and increased pressure, in turn helping to loosen pulmonary secretions. When providing instructions on flutter valve use, teach the patient to inhale deeply, hold the breath for 2 to 3 seconds, and then exhale into the flutter valve. Advise him to use the valve up to four times daily, with 10 to 15 repetitions per session. If he’s using a prescribed bronchodilator, instruct him to use the drug before the flutter valve to help mobilize secretions. Breathing techniques for COPD patients Shortness of breath results from trapped, stale air. In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), clogged, narrow airways or damaged alveoli exacerbate air trapping. As part of pulmonary rehabilitation, patients typically are taught special breathing techniques, such as pursed-lip breathing and diaphragmatic breathing, that reduce air trapping and bring other respiratory benefits. Pulmonary rehabilitation programs Pursed-lip breathing are designed to optimize the paPursed-lip breathing improves ventilation by promoting movement of old air out of the tient’s physical and social performlungs and increasing airway pressure, which helps keep the airway open. As exhalations ance. Goals include improving lengthen, the respiratory rate slows and the work of breathing declines, in turn relieving physical endurance and respiratory shortness of breath and causing general relaxation. muscle strength, easing symptoms, To teach your patient how to perform pursed-lip breathing, demonstrate the following and improving quality of life. steps and request a return demonstration: Tailored to each patient, these 1. Relax your shoulders and neck muscles. 2. Close your mouth and inhale slowly through your nose, as if you’re smelling roses. multidisciplinary programs teach 3. Purse your lips as if blowing out a candle. COPD patients about the disease 4. Exhale slowly through your lips, as if blowing out a candle, for at least a count of three. process, self-care, exercise, medications, and proper nutrition. They Diaphragmatic breathing focus on lower and upper extremiDiaphragmatic breathing strengthens the diaphragm and decreases the respiratory rate ty exercise and conditioning, and oxygen demand. As a result, the overall work of breathing eases. To teach diaphragbreathing retraining, education, and matic breathing, demonstrate the following steps and request a return demonstration: psychosocial support. 1. Relax your shoulders and neck muscles. In hospital settings, pulmonary 2. Place your hands on your abdomen. 3. Inhale slowly through your nose and relax your stomach muscles. As you do this, feel rehabilitation typically involves the your abdomen move against your hands. use of special breathing techniques, 4. Exhale slowly though your pursed lips as you tighten your abdominal muscles. Feel a flutter valve, and incentive spiyour abdomen move away from your hands as you exhale. rometry to mobilize pulmonary secretions and improve respiratory effort. (See Breathing techniques for COPD patients and • lung volume reduction surgery (removal of certain Teaching patients how to use a flutter valve.) lung portions) Before discharge from an acute-care setting, the pa• lung transplantation. tient should be evaluated for eligibility for outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation. Ventilatory support Although ventilatory support hasn’t been proven effecSurgical treatment tive in routine management of stable COPD, evidence Reserved for patients with severe COPD, surgery may suggests noninvasive mechanical ventilation helps durinvolve: ing acute exacerbations in patients with hypercapnea • bullectomy (removal of distended, nonfunctional (elevated CO2 and blood pH below 7.35). This type of pulmonary air spaces) ventilation reduces the work of breathing, improves 14 American Nurse Today December 2006 ventilation, decreases the respiratory rate, increases tidal volume, boosts oxygenation, reduces acidosis, and decreases mortality rates. Expected patient outcomes include decreased length of stay in the intensive care unit and decreased incidence of infection. Noninvasive ventilation is delivered by a nasal or face mask—usually in the form of bilevel positive airway pressure (BIPAP) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). • BIPAP provides continuous highflow positive pressure, which cycles between high positive pressure during inhalation and lower positive pressure during exhalation. • CPAP provides continuous highflow positive pressure set at a constant pressure. As the underlying condition improves, use of the ventilation device is decreased. Once the patient’s condition stabilizes, ventilatory support is discontinued. Patients who need ventilatory assistance but don’t respond to noninvasive mechanical ventilation may require intubation. Supporting your patient as COPD progresses Despite high-quality care, COPD patients gradually progress toward the end stages of the disease. Over time, they may require more frequent hospital stays and may have shorter intervals between exacerbations. Yet, despite this inevitable decline, your expertise and knowledge regarding COPD assessment and management can enhance your patient’s survival and improve quality of life. Inform patients that with proper care, the disease can be managed and its progress can be slowed. Provide emotional support to the patient and family and, as appropriate, refer them for counseling. ✯ Selected references American Thoracic Society. ATS statement: pulmonary rehabilitation—1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999:159:1673. Braman, S. Update on the ATS guidelines for COPD. Medscape Pulmonary Medicine. 2005; 9(1). Available at: www.medscape.com/ viewarticle/498648. Accessed October 14, 2006. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD; GOLD executive summary (2005 update). Available at: www.goldcopd.com/ Guidelineitem.asp?l1=2&l2=1&intId=996. Accessed September 28, 2006. Huang M, Singer LG. Surgical interventions for COPD. Geriatrics Aging. 2005;8(3):40-46. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Morbidity and Mortality: 2004 Chartbook on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Diseases. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/ cht-book.htm. Accessed September 28, 2006. Mary Lou Warren, MSN, RN, CNS-CC, CCRN, is a Clinical Nurse Specialist in the Intensive Care Unit at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Tex. Sarah Livesay, BSN, RN, is Neuroscience Outcomes Manager at St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital in Houston. The possiblities are endless "NFSJ DBO /VSTJ OH 4FSWJ DFT J OD /VSTF 'J STU 4UBGGJ OH Per Diem & Travel Nursing! Excellent Pay & Bonuses 100% Daily Instant Pay & Direct Deposit Incentives Insurance & 401(k) Local & Travel Contracts Nationwide Contracts Available Now (866) 362-8540 | (800) 444-6877 www.american-nurse.com December 2006 American Nurse Today 15