The Mechanics of Breathing

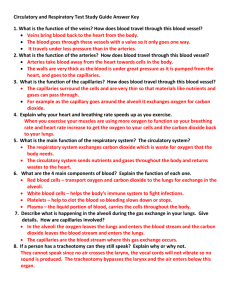

advertisement

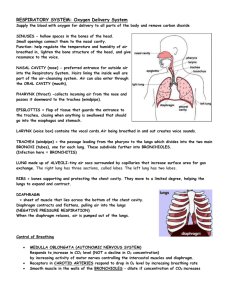

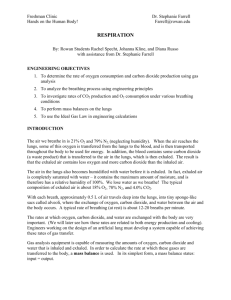

The Mechanics of Breathing The action of breathing in and out is due to changes of pressure within the thorax, in comparison with the outside. When we inhale the intercostal muscles (between the ribs) and diaphragm contract to expand the chest cavity. The diaphragm flattens and moves downwards and the intercostal muscles move the rib cage upwards and out. This increase in size decreases the internal air pressure and also air from the outside (at a now higher pressure than inside the thorax) rushes into the lungs to equalize the pressures. When we exhale, the diaphragm and intercostal muscles relax and return to their resting positions. This reduces the size of the thoracic cavity, thereby increasing the pressure and forcing air out of the lungs. Breathing Rate The rate at which we inhale and exhale is controlled by the respiratory centre, within the Medulla Oblongata in the brain. Inspiration occurs due to increased firing of inspiratory nerves and also the increased recruitment of motor units within the intercostals and diaphragm. Exhalation occurs due to a sudden stop in impulses along the inspiratory nerves. Our lungs are prevented from excess inspiration due to stretch receptors within the bronchi and bronchioles which send impulses to the Medulla Oblongata when stimulated. Breathing rate is all controlled by chemoreceptors within the main arteries which monitor the levels of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide within the blood. If oxygen saturation falls, ventilation accelerates to increase the volume of Oxygen inspired. If levels of Carbon Dioxide increase a substance known as carbonic acid is released into the blood which causes Hydrogen ions (H+) to be formed. An increased concentration of H+ in the blood stimulates increased ventilation rates. This also occurs when lactic acid is released into the blood following high intensity exercise. Respiratory Volumes Respiratory volumes are the amount of air inhaled, exhaled and stored within the lungs at any given time Tidal Volume: The amount of air which enters the lungs during normal inhalation at rest. The average tidal volume is 500ml. The same amount leaves the lungs during exhalation. Inspiratory Reserve Volume: The amount of extra air inhaled (above tidal volume) during a deep breath. This can be as high as 3000ml. Expiratory Reserve Volume: The amount of extra air exhaled (above tidal volume) during a forceful breath out. Residual Volume: The amount of air left in the lungs following a maximal exhalation. There is always some air remaining to prevent the lungs from collapsing. Vital Capacity: The most air you can exhale after taking the deepest breath you can. It can be up to ten times more than you would normally exhale. Total Lung Capacity: This is the vital lung capacity plus the residual volume and is the total amount of air the lungs can hold. The average total lung capacity is 6000ml, although this varies with age, height, sex and health. Gaseous Exchange The main function of the respiratory system is gaseous exchange. This refers to the process of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide moving between the lungs and blood: Diffusion occurs when molecules move from an area of high concentration (of that molecule) to an area of low concentration. This occurs during gaseous exchange as the blood in the capillaries surrounding the alveoli has a lower oxygen concentration of Oxygen than the air in the alveoli which has just been inhaled. Both alveoli and capillaries have walls which are only one cell thick and allow gases to diffuse across them. The same happens with Carbon Dioxide (CO2). The blood in the surrounding capillaries has a higher concentration of CO2 than the inspired air due to it being a waste product of energy production. Therefore CO2 diffuses the other way, from the capillaries, into the alveoli where it can then be exhaled. To demonstrate the use of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide in respiration you can look at the amounts of both gases which we inhale and then exhale. The air we breathe contains approximately 21% Oxygen and 0.04% Carbon Dioxide. When we exhale there is approximately 17% Oxygen and 3% Carbon Dioxide. This shows a decrease in Oxygen levels (as it is used in producing energy) and an increase in Carbon Dioxide due to it being a waste product of energy production. VO2 Max VO2 max is the measure of the peak volume of Oxygen (VO2) you can consume and use in a minute. It is measured in ml/kg/min and so you can see that it is also relative to body weight. As we already know, Oxygen is needed to produce energy. The harder you exercise the more Oxygen you use in order to produce sufficient energy. However, everybody has a maximum level (their VO2 Max), where Oxygen utilization is at its peak If exercise intensity increases beyond this point then the anaerobic energy systems must be used to supply the additional energy. However, anaerobic metabolism produces lactic acid which causes fatigue and so cannot be sustained. Anaerobic energy production also results in Oxygen Debt. Your VO2 Max can be increased through training, as this causes adaptations within the cardiovascular, respiratory and muscular systems which make the processes of gas exchange, Oxygen transport and aerobic metabolism more efficient. There are a number of ways of testing your VO2 max. The most accurate is in a laboratory, where exhaled Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide levels are measured whilst running on a treadmill. This allows us to see how much of the Oxygen inhaled (we know 21% of the air we inhale is O2) is used for energy production. VO2 can also be estimated using tests such as a bleep test, or Balke test. Results vary depending on fitness level, sex, age and genetics. The older you are the lower your VO2 Max is estimated to be. An average score for a twentysomething male would be 40 ml/kg/min with an excellent score being 52 ml/kg/min. An average score for a female of the same age would be 30 ml/kg/min and an excellent score would be 41 ml/kg/min. Some professional sports people (involved in endurance activities) have scores in the 80's!