pdf - University Of Nigeria Nsukka

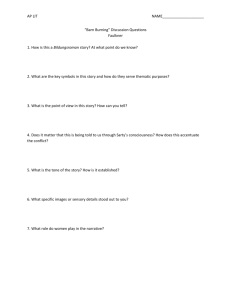

advertisement