Part 3 - Delaware Journal of Corporate Law

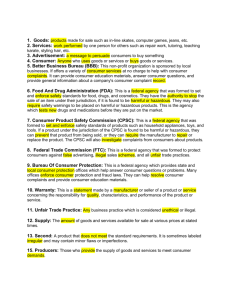

advertisement