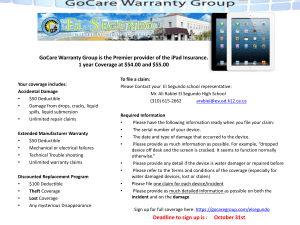

COMMERCIAL CODE §2-318*-The Uniform Com

advertisement

NATURAL RESOURCES JOURNAL [VOL. 4 WARRANTY-THE PRIVITY REQUIREMENT-PRODUCTS LIABILITY COMMERCIAL CODE §2-318*-The Uniform Commercial Code was adopted by New Mexico in 1961.1 Section 2-318 of the Code reads as follows: -UNIFORM A Seller's warranty whether express or implied extends to any natural person who is in the family or household of his buyer or who is a guest in his home if it is reasonable to expect that such person may use, consume or be affected by the goods and who is injured in person by breach of the warranty. A seller may not exclude or limit 2 the operation of this section. The New Mexico Supreme Court has not interpreted this section; but recent decisions in Pennsylvania 3 and other jurisdictions,' the purposeful omission of section 2-318 from the Code by the Cali- fornia legislature, 5 and the sweeping changes made to section 2-3 18 by the Wyoming" and Virginia 7 legislatures demonstrate that section 2-318 should be reexamined and revised by New Mexico. The question of whether privity of contract is essential to an action for breach of product warranty against the manufacturer has been the subject of long controversy, resulting in a great number of 0 Hochgertel v. Canada Dry Corp., 409 Pa. 610, 187 A.2d 575 (1963); Yentzer v. Taylor Wine Co., 414 Pa. 272, 199 A.2d 463 (1964). 1. New Mexico's version of the Uniform Commercial Code, N.M. Stat. Ann. §§ 50A-1101 to -9-507 (Repl. 1962), is based on the 1958 Official Text, promulgated jointly by the American Law Institute and the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. All references to New Mexico's version of the Code, often designated "UCC" both in footnotes and text, will omit the full statutory citation. 2. UCC § 2-318. 3. Hochgertel v. Canada Dry Corp., 409 Pa. 610, 187 A.2d 575 (1963); Yentzer v. Taylor Wine Co., 414 Pa. 272, 199 A. 2d 463 (1964). 4. E.g., Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors, Inc., 32 N.J. 358, 161 A.2d 69 (1960), Annot., 75 A.L.R.2d 1 (1960) ; Green v. American Tobacco Co., 154 So. 2d 169 (Fla. 1963) ; Morrow v. Caloric Appliance Corp., 372 S.W. 2d 41 (Mo. 1963) ; Randy Knitwear, Inc., v. American Cyanamid Co., 11 N.Y. 2d 5, 181 N.E. 2d 399 (1962) ; Picker X-Ray Corp. v. General Motors Corp., 185 A.2d 919 (D.C. Munic. Ct. App. 1962); Peterson v. Lamb Rubber Co., 343 P.2d 261 (Cal. 2d Dist. Ct. App. 1959) (supporting abandonment of privity in breach of warranty actions). But see Barnard v. Pennsylvania Range Boiler Co., 216 F. Supp. 560 (E.D. Pa. 1963), in which Massachusetts law is interpreted as strictly requiring privity. 5. Cal. Commercial Code § 2318. 6. Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 34-2-218 (Supp. 1963). 7. Va. Acts 1964, ch. 219. The UCC becomes effective January 1, 1966. Virginia had JANUARY, 1965] COMMENTS judicial decisions and a profuse literature. 8 The drafters of the Code were prepared to abolish the privity requirement. The May, 1949 draft of the Code clearly did abolish it,9 and the Proposed Final Draft retained the same provision.' 0 It was not until the publication of Proposed Final Draft No. 2 that the present wording of section 2-318 appeared." In an understatement, the Editorial Board of the American Law Institute indicated2 that a "minor change of substance" had been made in the section.1 Pennsylvania became the first state to adopt the Code in 1953.' dispensed with the privity requirement in 1962 by statute, Va. Stat. § 8-654.3 (Supp. 1962) which reads: Lack of privity between plaintiff and defendant shall be no defense in any action brought against the manufacturer or seller of goods to recover damages for breach of warranty, express or implied, or for negligence, although the plaintiff did not purchase the goods from the defendant, if the plaintiff was a person whom the manufacturer or seller might reasonably have expected to use, consume, or be affected by the goods; however, this section shall not be construed to affect any litigation pending at its effective date. Except that the date "June twenty-nine, nineteen hundred sixty-two" is substituted for the last words "at its effective date" above, the version of section 2-318 adopted by the Virginia Assembly is identical with the above statute. 8. Prosser, The Assault Upon the Citadel (Strict Liability to the Consumer), 69 Yale L.J. 1099 (1960). [Hereinafter cited as The Assault.] In this prodigious article, Dean Prosser makes over 900 citations to cases, and over 100 citations to law review articles, treatises, and statutes. It is not appropriate for this comment to attempt reference to the multitude of cases, articles, treatises, etc. The reader is referred to The Assault, supra; Annot., 75 A.L.R.2d 39 (1961), and Annot., 74 A.L.R.2d 1111 (1960), for a comprehensive listing. 9. UCC § 2-318, May 1949 Draft, reads: A warranty whether express or implied extends to any natural person who is in the family or household of the buyer or who is his guest or one whose relationship to him to such as to make it reasonable to expect that such person may use, consume or be affected by the goods and who is injured in person by breach of warranty. A seller may not exclude or limit the operation of this section. Comment 1 reads in part as follows: This section, following the dominant trend of judicial opinion developed in the light of modern distribution . . . is intended to broaden the right and remedy of the consumer in warranty, to free them from any technical rules to 'privity.' Comment 2 says in part: [E]mployees of an industrial consumer are covered. 10. UCC § 2-318, Proposed Final Draft (Spring 1950). 11. UCC § 2-318, Proposed Final Draft No. 2 (Spring 1951). 12. Ibid. The Symbol "AA" at the section is interpreted to mean "minor change of substance" in the foreword. 13. Braucher, The Uniform Commercial Code-A Third Look, 14 W. Res. L. Rev. 7 (1962). At note 1, Mr. Braucher lists the first eighteen states to adopt the UCC in chronological order. NATURAL RESOURCES JOURNAL [VOL. 4 In that same year the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, in a frequently cited case,' 4 approved the application of the res ipsa loquitur doctrine and the theory of exclusive control' 5 to an extent which resulted in shifting the burden of proof from the plaintiff to the defendant in nearly every action brought for injury arising from product defect. Although this was an oblique approach, the decision did alleviate the problems faced by an injured party who was not in privity with the seller or manufacturer. Some authorities concluded that other decisions in Pennsylvania had completely abrogated the requirement for privity in warranty cases.' 6 In 1959, the Superior Court of Pennsylvania said: A person, who after the purchase of a thing, has been damaged because of its unfitness for the intended purpose may bring an action in assumpsit against the manufacturer based on a breach of implied warranty of fitness; and proof of a contractual relationship or privity between the manufacturer and the purchaser is not necessary to im17 pose liability for the damage. Dean Prosser seemed amply justified in saying that Pennsylvania applied strict liability to the sale of food.' There was also some justification for a conclusion that Pennsylvania had abandoned the requirement of privity in all product warranty actions. Section 2-318 of the Code frees from the technical requirements of privity only the buyer's family, the members of his household, and his guests.' Could it be interpreted that the section covered employees as members of his employer's "family" or "household"? Dean Prosser in 1960 confidently predicted that when the case turned up, the employee would be so considered.2 ° In 1960 the Cal14. Loch v. Confair, 373 Pa. 212, 93 A.2d 451 (1953). 15. The Assault, supra note 8, at 1114. In speaking of the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur, Dean Prosser says that "Pennsylvania has a doctrine of 'exclusive control,' which has the same effect." Id. at 1114, n.121. 16. Mannsz v. MacWhyte, 155 F.2d 445, 449-50 (3d Cir. 1946). The court, interpreting Pennsylvania law, said: We think it clear that whether the approach to the problem be by way of warranty or under the doctrine of negligence, the requirement of privity between the injured party and the manufacturer of the product which has injured him has been obliterated from the Pennsylvania law. 17. Jarnot v. Ford Motor Co., 191 Pa. Super. 422, 430, 156 A.2d 568, 572 (1959). 18. The Assault, supra note 8, at 1117, n.127. 19. UCC § 2-318. 20. The Assault, supra note 8, at 1142. JANUARY, 1965] COMMENTS ifornia Supreme Court lent credence to this prediction by the statement that an "employee should be considered a member of the industrial 'family' of the employer." 2 But in 1963 the Pennsylvania Supreme Court firmly disagreed with Dean Prosser's confident prediction. In Hochgertel v. Canada Dry Corp.,22 the court held: It is clear from the language used [in § 2-318] that in order to qualify as a person (not a buyer), who is within the protection of the warranty, one must be a member of the buyer's family, his household or a guest in his home. An employee is definitely in none of these 23 categories. The court refers by footnote to a Connecticut case 2 4 where it was held that a maid was not a member of the buyer's household. Noting, however, that the Code was not intended to restrict the case law in the field, the court made a study of "pertinent Pennsylvania authorities ' 25 to determine whether warranty could be extended to an employee. The court said: [I]t is now established beyond argument in Pennsylvania that a subpurchaser may sue the manufacturer directly in food cases for a breach of implied warranty of fitness regardless of the lack of privity. 26 (Emphasis added.) In limitation of that rule, however, the court said: In no case in Pennsylvania has recovery against the manufacturer for breach of an implied warranty been extended beyond a purchaser in the distributive chain. In fact, the inescapable conclusion from Loch v. Confair, 361 Pa. 158, 63 A.2d 24 (1949), is that no warranty will be implied in favor of one who is not in the category of a 27 purchaser. The court excepts from this limitation those individuals (members of the buyer's family or household) within the extended coverage 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. Peterson v. Lamb Rubber Co., 54 Cal. 2d 339, 348, 353 P.2d 575, 581 (1960). 409 Pa. 610,187 A.2d 575 (1963). 187 A.2d at 577. Duart v. Axton-Cross Co., 19 Conn. Supp. 188, 110 A.2d 647 (C.P. 1963). Hochgertel v. Canada Dry Corp., 409 Pa. 610, 187 A.2d 575, 578 (1963). Ibid. Ibid. NATURAL RESOURCES JOURNAL [VOL. 4 of the Code.2 1 In its closing paragraph the court points out that it considers the plaintiff to have an adequate remedy in trespass.2 9 One year after Hochgertel, the case of Yentzer v. Taylor Wine Co.3 0 was brought before the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. In Yentzer, the plaintiff hotel manager, acting for his employer, purchased four bottles of champagne from a local liquor outlet. The champagne was manufactured and bottled by the defendant, and was intended for the consumption of hotel guests. While the plaintiff and other employees were preparing to serve the wine, a cork from one of the bottles ejected and struck the plaintiff in the eye, causing serious injury. The plaintiff brought suit, alleging breach of implied warranties of fitness for the intended use and of safe packaging. The lower court found the decision in Hochgertel to be controlling and dismissed the complaint. The supreme court, however, reversed on the ground that the plaintiff, as the actual buyer of the champagne, was entitled to bring suit against the manufacturer for breach of implied warranty, even though he acted as an employee in purchasing the wine." The supreme court noted that an employee was not a person to whom the benefit of warranty extended under section 2-3 18, but maintained that the statement of Pennsylvania case law granting such benefit to the subpurchaser did not "foreclose the inclusion of ' 82 the actual purchaser even though he be an employee. 28. Comment 3 to § 2-318 provides: This section expressly includes as beneficiaries within its provisions the family, household, and guests of the purchaser. Beyond this, the section is neutral and is not intended to enlarge or restrict the developing case law on whether the seller's warranties, given to his buyer who resells, extend to other persons in the distributive chain. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court's determination that the benefit of implied warranty extended only to subpurchasers (in "food" cases) is in accord with a possible interpretation of Comment 3. The denial of any intention to enlarge or restrict case law as it affects "other persons in the distributive chain" can be considered to limit the extension to subpurchasers only. Pennsylvania had previously developed the position that subpurchasers in "food" cases were entitled to bring suit for product injury directly against the manufacturer on the ground of implied warranty, and no enlargement or restriction could be accomplished by the UCC. It can thus be argued that § 2-318 and Comment 3 provide no leeway which would allow courts to extend implied warranty protection to persons, not within the specific provisions of § 2-318, who are not subpurchasers. See Hochgertel v. Canada Dry Corp., 409 Pa. 610, 187 A.2d 575, 577 (1963). 29. 187 A.2d at 579. 30. 414 Pa. 272, 199 A.2d 463 (1964). 31. 199 A.2d at 464. 32. Ibid. JANUARY, 1965] COMMENTS Relying upon the definition of "buyers" found in section 2-103 of the Code,3 3 the supreme court found the plaintiff to be "clearly a buyer" and "in the distributive chain." He was, therefore, under Pennsylvania case law, entitled to the benefit of warranty and right of action against the manufacturer. The transition of the position of the plaintiff as a "buyer" under the Code to a "purchaser" protected under case law was made without comment or explanation. This did not go unchallenged. Justice Eagan, with whom Chief Justice Bell joined, dissented vigorously. Justice Eagan called attention to the definitions of "purchase" and "purchaser" in section 1-201(32), (33) of the Code.3 4 He maintained that these definitions required creation of an interest in the property before the taker could rightly be called a purchaser. An employee, buying on behalf of his employer, obtained no interest in the property, and could not be a purchaser.3 ' The dissent further alleges that "firmly entrenched principles of agency law" deny that an employee who buys for his employer can be a purchaser,"' and that the case is not a "food" case, but is one bottomed upon inadequate packaging. The majority opinion simply assumes that it is a "food" case. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania stated in Hochgertel the firm principle that an employee is not one of the persons entitled to the benefit of warranty protection either under the Code or the case law of the state. The Yentzer case provides the first exception to that rule; i.e., that an employee who buys a product for his employer is given the benefit of warranty as a "purchaser" under Pennsylvania case law. Allowing the employee-buyer to bring suit in warranty directly against the manufacturer, but excluding all other employees of the purchaser, makes small sense if persons most likely to use or consume the product are to have a right of action directly against the manufacturer. In discussing the development of strict liability in "food" cases, Dean Prosser wrote: 33. UCC §2-103 (1) (a). The definition reads: 'Buyer' means a person who buys or contracts to buy goods." 34. UCC § 1-201 (32) and (33). The definitions read: "(32) 'Purchase' includes any taking by sale, discount, negotiation, mortgage, pledge, lien, issue or re-issue, gift or any other voluntary transaction creating an interest in the property. "(33) 'Purchaser' means a person who takes by purchase." 35. Yentzer v,Taylor Wine Co., 414 Pa. 272, 199 A.2d 463 (1964). 36. Webster's New International Dictionary (2d ed. 1960) under definition of "buy" says: "Buy, purchase are in meaning convertible terms," NATURAL RESOURCES JOURNAL [VOL. 4 [T]here was an extended period during which courts proceeded to invent a remarkable variety of highly ingenious, and equally unconvincing theories . . . to get around the lack of privity between the plaintiff and defendant. The unusual industry of Mr. Cornelius W. Gillam3 7 has collected no less than twenty-nine such triumphs of juridical technique. ....38 In a footnote he then summarizes these twenty-nine "triumphs of juridical technique." 39 It seems fair to ask if the Yentzer decision constitutes example number 30 or does it begin a series of twenty-nine examples in the new era of the Uniform Commercial Code? In either case it is travel into the morass of exceptions which surrounds the rule of privity in warranty actions. In any event, the Yentzer decision found it necessary to provide the exception to section 2-318 by resort to Pennsylvania case law. The Code section must then be considered as an impediment which blocks the trend toward relaxation of the privity rule in warranty cases, rather than an aid or encouragement to the trend. In 1963 California became the twenty-eighth state to adopt the Code, 40 but specifically omitted section 2-318. 41 The recommendations for omission considered the section to be a "step backward" which would "contract the scope of a seller's warranty under the California decisions." 42 Only two states have modified section 2-3 18 of the Code in such a manner as to "anticipate the trend of the American case laws somewhat and cast privity to the winds."' 43 Wyoming adopted the UCC in 1961 (effective January 1, 1962) 44 and as adopted by that state section 2-3 18 reads: A seller's warranty whether express or implied extends to any person who may reasonably be expected to use, consume, or be affected 37. Gillam, Products Liability in a Nutshell, 37 Ore. L. Rev. 119, 153-55 (1957). 38. The Assault, supra note 8, at 1124. 39. Id. at 1124, n.153. 40. Cal. Commercial Code, ch. 23A, General Introduction at p. LVII. As of Sept. 16, 1964, thirty jurisdictions (29 states and D.C.) have adopted the Code. 1 CCH Installment Credit Guide 700 (1964). 41. Cal. Commercial Code § 2318. 42. Cal. Commercial Code § 2318, Comment 1. 43. Wyo. Legislative Research Comm., Research Publication No. 1, The Uniform Commercial Code, (July, 1960), at p. 40. Pertinent portion of this publication appears in Carrington, The Uniform Commercial Code-Sales, Bulk Sales and Documents of Title, 15 Wyo. L.J. 1, 11 (1960). 44. Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 34-10-105 (Supp. 1963). JANUARY, 1965] COMMENTS by the goods and who is injured by breach of the warranty. A seller 45 may not exclude or limit the operation of this section. Virginia has modified the section 41 to accomplish the same resultthe abolishment of privity as a defense. The abolition of the requirement of privity in products liability has been a continuing process, supported by a variety of doctrines. Professor David H. Vernon has, in one short comment, succeeded in amalgamating them all when he says: [I]t should be recognized that the true basis for the destruction of privity is merely that, as a matter of public policy, it is felt that the technical requirements of privity have no place in a national distrib47 utive system such as we have in the United States. The established trend is toward the abrogation of privity, either by judicial pronouncement or by statutory action. A re-examination and revision of section 2-3 18 is recommended for New Mexico. The Wyoming formulation appears to be a satisfactory model to follow. 48 JOHN N. URTES 45. Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 34-2-318 (Supp. 1963). 46. See note 7 supra. 47. Vernon, The Uniform Commercial Code and New Mexico, Article 2-Sales 23, (Div. of Research, Dept. of Government, Univ. of N.M. Publ. No. 50, 1957). 48. Braucher, The Uniform Commercial Code-A Third Look, 14 W. Res. L. Rev. 7, 15-16 (1962). The author recommends the Wyoming formulation to the Permanent Editorial Board of the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws as "acceptable."