Reynolds v. County of Dauphin, PA

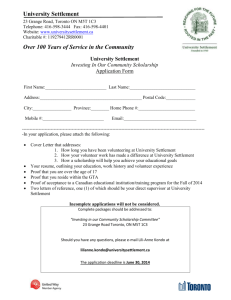

advertisement