Membership Incentives

advertisement

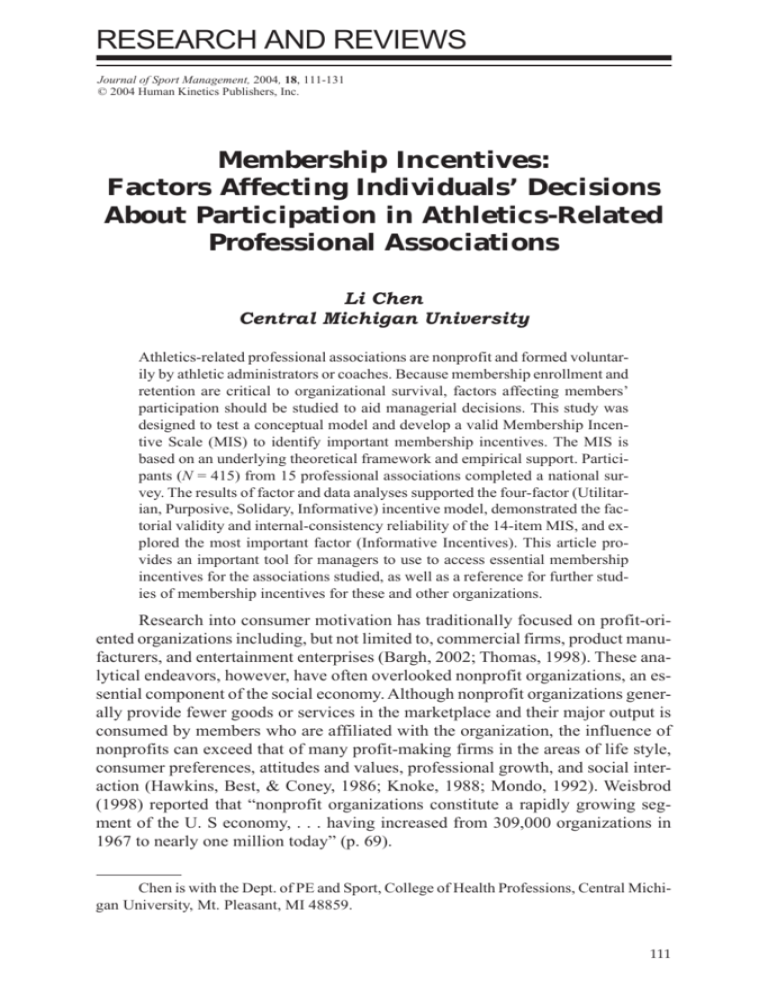

RESEARCH AND REVIEWS Membership Incentives 111 Journal of Sport Management, 2004, 18, 111-131 © 2004 Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc. Membership Incentives: Factors Affecting Individuals’ Decisions About Participation in Athletics-Related Professional Associations Li Chen Central Michigan University Athletics-related professional associations are nonprofit and formed voluntarily by athletic administrators or coaches. Because membership enrollment and retention are critical to organizational survival, factors affecting members’ participation should be studied to aid managerial decisions. This study was designed to test a conceptual model and develop a valid Membership Incentive Scale (MIS) to identify important membership incentives. The MIS is based on an underlying theoretical framework and empirical support. Participants (N = 415) from 15 professional associations completed a national survey. The results of factor and data analyses supported the four-factor (Utilitarian, Purposive, Solidary, Informative) incentive model, demonstrated the factorial validity and internal-consistency reliability of the 14-item MIS, and explored the most important factor (Informative Incentives). This article provides an important tool for managers to use to access essential membership incentives for the associations studied, as well as a reference for further studies of membership incentives for these and other organizations. Research into consumer motivation has traditionally focused on profit-oriented organizations including, but not limited to, commercial firms, product manufacturers, and entertainment enterprises (Bargh, 2002; Thomas, 1998). These analytical endeavors, however, have often overlooked nonprofit organizations, an essential component of the social economy. Although nonprofit organizations generally provide fewer goods or services in the marketplace and their major output is consumed by members who are affiliated with the organization, the influence of nonprofits can exceed that of many profit-making firms in the areas of life style, consumer preferences, attitudes and values, professional growth, and social interaction (Hawkins, Best, & Coney, 1986; Knoke, 1988; Mondo, 1992). Weisbrod (1998) reported that “nonprofit organizations constitute a rapidly growing segment of the U. S economy, . . . having increased from 309,000 organizations in 1967 to nearly one million today” (p. 69). Chen is with the Dept. of PE and Sport, College of Health Professions, Central Michigan University, Mt. Pleasant, MI 48859. 111 112 Chen Athletics-related professional associations (e.g., National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics [NACDA], Women’s Basketball Coaches Association) are nonprofit organizations voluntarily formed by professionals who hold administrative or coaching positions mainly in collegiate athletics. Such associations have demonstrated not only consistent stability but also continuous growth that can be demonstrated by their increasing membership enrollments. For instance, the number of NACDA members has increased approximately 20% in less than five years; registration fees for conventions and membership dues ($290 for a single member in 2003) have increased as well. Although members’ contributions and participation have been integrated into the entire marketing strategy by organizational decision makers, research findings from the disciplines of economics, sociology, political science, and leisure and recreation are revealing incentive systems in nonprofit associations (Caldwell & Andereck, 1994; Clark & Wilson, 1961; Knoke, 1988; Mondo, 1992; Olson, 1971). There is a dearth of research on membership incentives associated with professional societies in athletics-related settings, however. What factors affect the decisions of athletic administrators and coaches regarding enrolling and continuing their memberships in athletics-related associations? In order to answer this question, the researcher undertook a factor analysis of membership incentives offered by athletics-related professional associations. Conceptual Framework Organizational topologists (e.g., Clark & Wilson, 1961; Gordon & Babchuk, 1959; Knoke & Prensky, 1984; Mondo, 1992; Weisbrod, 1998) defined voluntary associations as nonprofits because of their characteristics of nonownership, profit used for input, and tax-exempt status. In these associations “participants do not derive their livelihoods from the organizations’ activities” (Knoke & Prenskey, 1984, p. 3); members’ participation in and contributions to these associations are based on accords and beliefs held in common with the group rather than their own compulsive efforts (Gordon & Babchuk, 1959; Mondo, 1992). Among voluntary organizations, about 66.4% are professional associations that recruit their members by providing selective benefits or occupational enhancements, and they tend to resemble a guild (Knoke, 1988; Olson, 1971). Education and occupation are central attributes of members of professional associations; these individuals are in recognized disciplines and have acquired preparatory skill and knowledge. Thus, “their social position is achieved primarily by their occupations and career orientation” (Hawkins et al., 1986, p. 179). Because membership dues, time, and energy contributed by the members are the primary resources of these associations, individuals’ motives to become members and organizational inducements to attract members constitute an interactive system from which the association can generate membership commitments. A motive (incentive) is a tendency related to an invisible internal force that stimulates or compels a desired reaction toward certain behaviors (Hawkins et al., 1986). The members tend to be either self-interest oriented (Bargh, 2002; Thomas, 1998) Membership Incentives 113 or desire “to gratify their facilitative needs” (Knoke & Wood, 1981, p. 33) in order either to use the organizational resources finitely (Mondo, 1992) or to seek prestige, respect, and friendship within the profession (Olson, 1971). Individuals tend to be more interested in incentives closely linked with occupational benefits, therefore organizational opportunities must match potential members predispositions in order to satisfy members when their participation is initiated (Knoke & Wright-Isak, 1982). Knoke (1988) found that the motives of association members fall into one of the following domains: (a) rational choice, which is the selection and maximization of the utility of associations; (b) affective bonding, which encompasses emotional attachment to the organization and its members; and (c) normative conformity, that is, conformation to social values and norms. These three motives are consistent with the three-factor (material, solidary, purposive) typology of incentives that has been viewed as the traditional model agreed on by many theorists of voluntary association (e.g., Clark & Wilson, 1961; Knoke, 1988; Mondo, 1992). Utilitarian Incentives Literature on voluntary associations delineates clearly that utilitarian incentives are commonly used to stimulate member commitments and contributions. Clark and Wilson (1961) claimed that material (utilitarian) incentives are tangible rewards with monetary value that serve individuals’ economic interests, and that utility-oriented organizations have often used material inducements to retain their members. Knoke (1988) and his colleagues (Knoke & Prensky, 1984; Knoke & Wood, 1981; Knoke & Wright-Isak, 1982) followed this direction and viewed utilitarian (material) incentives as a rational choice for members who value benefits that are offered exclusively to organizational members. Such material rewards can take the form of insurance plans, travel or rental discounts, subscriptions to publications and magazines, and ubiquitous products such as bags and T-shirts with printed logos. As indicated by Knoke and Prensky, these incentives attract contributions by rational individuals, and they allow potential contributors to calculate the costs of membership against the potential benefit. Additional benefits might include marketing and purchasing opportunities and certification or licensing programs, as well as various services provided to members (Knoke & Wright-Isak). In practice most professional associations provide utilitarian incentives to aid in the promotion of their programs, increase recruitment, and generate more inputs in the forms of voluntarism and donations (Weisbrod, 1998). Solidary Incentives If economics is the basis for utilitarian incentives, then social interaction would be the foundation for solidary incentives. Such incentives are intangible in nature, without monetary value, and are centered in the emotional attachment of members to their respective societies (Knoke, 1988; Olson, 1971). Clark and Wilson (1961) conceptualized that the key to solidary incentives is the desire for interpersonal relationships among the affiliated members and the attraction of formally organized events that build solidarity. For example, yearly conventions, parties, 114 Chen members’ luncheons, and recreational activities held by the associations provide the members an opportunity to socialize. Knoke and Wright-Isak (1982) described these incentives as social incentives or affective bonding. They indicated that individuals’ emotions are affected by three cues—organizational environment, symbolic expression, and coping behaviors of members—that function as the connection between psychophysiological states of individuals and the social interpretation of those states. Professional societies, in general, have promoted identification, socialization, congeniality, and a sense of belonging to the profession for the purpose of organizational cohesiveness. Such intangible benefits are inducements that satisfy participants: they include the sense of identity through membership, enjoyment of association activities, award-ceremony conviviality, and career distinction (Clark & Wilson, 1961; Gordon & Babchuk, 1959; Rotherberg, 1988). Purposive Incentives Similar to solidary incentives that relate to emotional attachment, purposive incentives represent intangible benefits as well. A purposive incentive links the purpose for individual involvement in an organization to organizational goals and standards (Clark & Wilson, 1961). Knoke and Wright-Isak (1982) indicated that these incentives (referred to as normative conformity) represent the intent of individuals to conform to social norms or occupational standards that are grounded in the organizational value system and the framework of normative regulations. According to Clark and Wilson (1961) and Knoke (1988), members’ commitments to associations and voluntary behaviors result from their intrinsic motivation to conform to social values, moral obligations, and standards of occupation. Therefore, the socially-instilled belief in appropriate action would be an explanation of a purposive behavior. In reality, many purposive-oriented associations demonstrate their ideologies and recruit contributors based on the intrinsic values of the contributors, which are consistent with the collective goals established by the associations (Knoke, 1988; Mondo, 1992). Additional reasons individuals might have for actively taking part in purposive-oriented organizational activities are securing leadership power, acquiring voting rights, and acheiving professional freedom (Knoke & Prensky, 1984). Regardless of the purposive incentive used, the underlying premise relates to social conformity, continuing input of resources, attaining organizational goals, and operating in a viable environment (Knoke & Wood, 1981; Rotherberg, 1988). Informative Incentives In addition to the three traditional incentives (utilitarian, solidary, purposive), Bargh (2002), Knoke (1988), and Sternthal and Craig (1982) assumed that obtaining information could be a possible motive for individuals to join and maintain membership in professional associations. As proposed by Knoke, the incentives related to information “take the form of publication, data services, and research” (p. 317). Informative incentives offered by the associations can be either tangible or intangible benefits for members. Tangible benefits might include news of job openings Membership Incentives 115 or discount programs available through the association that, when taken advantage of by members, provide an immediate financial benefit (Bargh). Intangible incentives might involve the availability of advanced knowledge and research data (Knoke) that could increase members’ knowledge and would be particularly useful in the education of junior members. Because we live in an information-based society and face 21st-century challenges, information is a valuable resource for success. The more valuable the information delivered by professional associations, the higher the likelihood that access to that information will influence individuals when making decisions (Sternthal & Craig, 1982), and the more likely the individuals would be to participate in an associational network that offers such access (Knoke, 1988). Annual conventions are a stimulating context for the dissemination of this kind of information to and among members. (Sternthal & Craig). Athletics-related professional associations share many characteristics with other professional societies in which heterogeneous inducements are expected. Material rewards are attractive to those who are still improving their social-economic status. In practice, many athletics-related professional associations (e.g., National Basketball Coaches’ Association, Intercollegiate Tennis Association) have offered material benefits such as discounted registration fees, various insurance programs, coach relocation services, and free subscriptions. In addition, to opportunities for professionals to socialize, the yearly conventions of athletics-related professional associations have served as occupational networks. Purposive incentives could facilitate intrinsic motivation for many professionals because improving the quality of the profession and pursuing career achievements are specific purposes of members, as well as declared objectives of the various associations of administrators and coaches. Athletics-related professional associations, however, differ from many other professional organizations. In addition to concerns regarding balanced organizational effectiveness and membership retention in coaches’ associations, Weisbrod (1998) indicated that the athletics-related associations have faced challenges in obtaining public support. For instance, only 4% of the total income of athleticsrelated professional associations was from public donations compared to the nonprofit litigation and legal-aid professional associations, which received 97% of their revenue from public donations. The differences might also include: (a) the fact that the organizations work closely with their governing bodies (e.g., National Collegiate Athletic Association [NCAA], National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics), (b) yearly conferences are often combined with entertainment events (championships), (c) associations encourage institutional (sustaining) memberships, (d) the athletics-related organizations have less political power to lobby the government compared with other professional associations (e.g., American Medical Association [Olson, 1971]), and (e) athletics-related organizations might provide more information about job openings at conventions and on websites. Because of the relative uncertainty of the job market in coaching, many members of athletic-related associations probably realize that obtaining current 116 Chen information benefits them in terms of mastering new knowledge and methods, which will help them maintain their marketability, and that maintaining professional contacts will assist with job transfers and occupational improvement. Athletic administrators want to acquire updated information and new methods to guide administrative decisions, coaches need more timely and informative materials about coaching trends, networking services (e.g., listserv e-mail), and the future direction of the sport. All of his will help personal growth and the achievements of their teams. Thus, informative incentives could be an essential component included in the incentive systems of the athletic-related associations. Previous researchers (e.g., Clarke, Price, Stewart, & Krause, 1978; Farrell, Johnston, & Twynam, 1998; Knoke, 1988) attempted to construct incentive inventories for examining individuals’ motives for participation based on an underlying trifactor (utilitarian, solidary, purposive) framework. Their studies were conducted in such settings as a political party (Ontario Liberals: Clarke et al., 1978); the social-economy-related nonprofits (voluntary organizations: Knoke, 1988); a recreation-related association (zoological society: Caldwell & Andereck, 1994); a public-interest organization (Common Cause: Mondo, 1992); and a group of volunteers in a Canadian elite sporting competition (Farrell et al., 1998). The numbers of incentive (motive) factors in their inventories ranged from three to six (10 to 28 items) to test specific motivational patterns for the different samples. Among these studies, the normative (purposive) incentives were found to be the most critical factor affecting individuals’ decisions about participation, followed by solidary incentives. Material (utilitarian) benefits were the least important incentives for membership enrollment. Information incentives were not included in the scales, except for Knoke’s (1988) study, which used “information” as a variable to test the organizational participants’ political orientation. Limited attention was given to this factor by the respondents, however, though the material and social incentives received more attention from the less politically oriented associations (Knoke). Although the instruments might be derived from sound conceptual bases and empirical observation, most of them are either sample specific in nature or were developed using improper procedures of instrument development; the instruments are neither adequate to show the reliabilities of contents and factors for the measurement properties, nor are they valid for measuring the membership incentives for the athletics-related professional associations. Purpose of the Study Why do administrators and coaches pay membership dues and spend time to engage in the activities organized by athletics-related professional associations? What possible incentives expected by these professionals could be reasonably clustered and constructed into a valid scale for athletics-related professional associations to use to assess organizational inducements? To date, limited data has been available in these areas. Because athletics-related professional associations might differ from other voluntary organizations in many ways (e.g., belief of members, financial support, use of information), a conceptually sound and empirically supported scale Membership Incentives 117 should be developed to meet the needs of continuing research and to provide a tool for managerial practitioners to use when evaluating membership incentives in athletics-related professional associations. In order to address these needs, a four-factor model illustrating decisions about participation by members of athletics-related associations was proposed (see Figure 1). Four possible incentives (utilitarian, solidary, purposive, informative) were specified and defined operationally (see Table 1) in terms of the underlying conceptual framework (e.g., Clark & Wilson, 1961; Knoke, 1988; Mondo, 1992; Olson, 1971) and the distinctive features of athletics-related professional associations. Therefore, the purposes of this study were to (a) explore essential items and important factors of membership motives for athletics-related professional associations, (b) construct a valid and reliable Membership Incentive Scale (MIS) for the managers of associations to use to measure essential incentives expected by the enrolled professionals, and (c) to confirm the proposed model regarding individuals’ decisions about participation statistically by obtaining quantitative support from athletic administrators and coaches. Method Participants A total of 415 participants voluntarily took part in the study by completing the survey package (50.61% return). Participants included 168 athletic administrators Figure 1 — Four-factor conceptual model of membership incentives for individuals deciding about belonging to athletics-related professional associations. 118 Table 1 Chen Operational Definitions of Four MIS Factors Factors Operational Definitions Utilitarian Incentives (UI) refer to the material rewards or tangible benefits given only to the members of the associations. Solidary Incentives (SI) reflect the members’ emotional attachment to the associations, and are beneficial to their occupational affinity, sense of belonging, professional identification, and friendship through the social interaction of the members. Purposive Incentives (PI) provide satisfaction for those who are intrinsically motivated to appeal to social norms, occupational standards and political ideologies underlying the organizational goals and value system. Informative Incentives (II) are the information provided by the associational network that could benefit the members either tangibly with timing or transferable value (e.g., discount programs, new jobs) or intangibly for their professional growth (e.g., research data, new knowledge). (49.41% return rate; 67% men, 33% women; athletic directors = 90, assistant or associate directors = 78; Division I, II, and III = 66, 43, and 59, respectively) and 247 head coaches (51.46% return rate; 76% men, 24% women; individual sports = 115, team sports = 132; Division I, II, and III = 87, 81, and 79, respectively). The participants were all active members of one of 15 professional associations.1 Number of years as members ranged from 0.5 to 28 for the administrators, with a mean of 9.60 ± 6.8, and from 1 to 38 years for the coaches, with a mean of 11.08 ± 7.23. Procedure and Analyses The content validation, data collection, and construct-validity and reliability testing were the three main phases of this study. During the first phase (content validation), the Membership Incentive Scale (MIS), initially consisting of 24 questions (items), was drafted within the conceptual framework. A panel of 12 experts was interviewed in order to gather comments and verify the content of factors and items. The panel was composed of eight head coaches and four intercollegiate athletic-program administrators, all of whom were current members of athleticsrelated professional associations. They were asked to cluster each of the randomly placed 24 items into four predefined factors. Using the criterion of 80% or more agreement by the evaluative experts, 20 items were retained and four problematic ones were dropped. The questionnaire starts with a short introduction and a leading Membership Incentives 119 statement: “I join or stay in my professional association because I want to.” The items were associated with a 5-point Likert scale (1 = least important, 5 = most important) and were randomly arranged to form a draft of the MIS. During the second phase (data collection), the researcher administered a mail survey using random selection procedures. A list of institutions affiliated with the NCAA was requested from the National Directory of Athletics (1998) that included the names and addresses of the administrators and coaches employed by each institution. The random sample (N = 720) consisted of 240 administrators and 480 head coaches and was selected equally from three NCAA divisions. To meet the statistical requirement of sufficient sample size for this study, an additional 100 participants (athletic administrators) were later selected randomly across three NCAA divisions. The final sample pool was 820. A survey package that included the 20-item preliminary MIS, an informedconsent form, a demographic-information sheet, and a self-addressed envelope was mailed to each selected participant. Respondents who were current association members were required to sign and return the informed-consent forms, their demographic information, and the completed preliminary MIS within 2 weeks. The data were then interpreted, classified, and saved for analysis in the third (testing) phase of the study. In the testing phase, the entire sample was randomly split into two halves (samples A and B). Sample A (n = 208) was treated as a calibration group and was tested in Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using the Principle Components Analysis (PCA) of the Statistical Package of Social Science, 10.0 (SPSS®, 1999). The researcher used EFA first because: (a) all drafted items underlying the characteristics of athletics-related professional associations were newly designed, particularly the items proposed for the new factor (Informative Incentives), and they had not been tested at all in previous studies; (b) the researcher, at this point, was still assumed to have less control of consistency between conceptually sound factors and item specifications statistically fitted to the expected factors (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998); and (c) identifying the interrelationships among items and reducing irrelevant variables with EFA was an effective step to develop a new instrument before using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) of structural equation modeling (SEM) that further specifies the indicators to the given latent variables (Boomsma, 2000; Hair et al., 1998). Sample B (n = 207) was treated as a validation group and served to confirm that the four-factor model fit the data. Referring to the criterion of minimum sample size for estimating an asymptotic covariance matrix in CFA, that is, k (k-1)/2, where k is the observed variable (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996a), the cases included in Sample B exceeded the requirement—14(14-1)/2 = 182, (k = 14)—and ensured the reliability of CFA estimates (Hair et al., 1998). The alpha-reliability (Cronbach, 1951) test of SPSS 10.0 was applied to examine the internal-consistency reliabilities for each factor in Samples A, B, and the entire (multiple) sample. The composite reliabilities and the variance-extracted measures were computed to assist examination of the internal consistency of the MIS constructs and to verify that the indicators accurately represent the latent constructs (Hair et al., 1998). 120 Chen Results Testing calibration sample. The basic assumptions of using EFA for the calibration sample (Sample A) were examined in SPSS 10.0. The magnitude of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy for the 20-item preliminary SMI was .818, indicating a satisfactory degree of common factor variance. The coefficient of Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity for the initial scale was significant (Χ2 = 1343.57, p < .001) and demonstrated its correlation magnitude significantly, differing from a given identity matrix (SPSS, 1999). Thus, EFA was suitable for use with Sample A. The Principle Component Analysis (PCA) was employed to explore correlation coefficients among the items and to identify the most parsimonious scale to preserve the measurement property (Stevens, 1996). The Direct Oblimin rotation of EFA was performed based on the nature of the oblique rotation (SPSS, 1999) for the data, and further consistent examination of the validation sample was done with CFA (both allow factors and/or latent variables to be intercorrelated, [Stevens]). Specifying Delta as zero and .40 as the criterion of factor loading for retention, 14 items with satisfactory factor loading (.869 [U2] to .567 [P9]) from the pattern matrix were retained and six items were dropped.2 The component correlation coefficients were .334, –.111, and .142 for PI with SI, II, and UI, respectively; .087 and –.051 for UI with SI and II, respectively; and –.217 for II with SI. The Eigenvalues (4.069–1.133), indicating that the four factors were significantly greater than 1.00, contributed 29.06%–8.10% variances to the solution, and revealed a 62.3% total variance in EFA. The values of community (h2) for the items ranged from .55 to .75, meeting the standards (Hair et al., 1998). Each of the extracted factors contains 3 or 4 items that were highly correlated with the expected constructs underlying the a priori conceptual framework. The means, standard deviations, values of h2, and factor loading (FL) of the retained 14 items of Sample A are presented in Table 2. Testing validation sample. It was assumed that the reduced 14-item structure from EFA for the calibration sample would fit the 4-factor model better, but an examination of the validation sample (Hair et al., 1998) was essential. Sample B, with the identical 14 items, was evaluated using CFA of SEM to ensure the factorial validity of MIS. The normality of the validation sample was tested using PRELIS 2.20 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996a). The values of normalized multivariate skewness (23.32) and multivariate kurtosis (232.82), similar to z scores (Motl & Conroy, 2000), were both significant (p < .001), indicating a multivariate nonnormality. Thus, the Asymptotic Distribution Free (ADF) with Weight Least Square (WLS) method was applied for the analysis (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996b). Specifying four latent variables to their respective indicators as shown in Table 1, CFA produced the coefficients of Lambda Chi (ΛΧ: standardized factor loading), Theta Delta (Θ∆: error associated with indicator only), and Phi (Φ: the interfactor correlation estimate) as shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. The coefficients of Θ∆, ranging from .62 to .94 (M = .77), were all above the .50 criterion and showed highly linear relationships between the items and their Membership Incentives 121 Table 2 Remaining 14 Items With Means (M), Standard Deviation (SD), Coefficients of h2, and Factor Loadings (FL) Using Direct Oblimin Rotation of EFA for Calibration Sample (n = 208) Factors UI SI PI II Items U1. Have more opportunities of leisure and recreation. U2. Obtain benefits of membership (discounts and programs). U3. Receive free journals, magazines, or membership gifts. S4. Gain affinitive feelings from organizational activities. S5. Have a sense of belonging to my prestigious profession. S6. Meet with my friends, colleagues, or celebrities. P7. Engage in collective decisions (voting, making policy). P8. Express my politic ideology and professional freedom. P9. Exercise my leadership or fellowship in the profession. P10. Appeal to social values and occupational standards. I11. Gather information regarding new jobs and programs. I12. Enhance understanding of updated knowledge and regulations. I13. Exchange new ideas and methods of administration and coaching. I14. Learn about future trends through networking. M SD h2 FL 2.33 .91 .66 .645 2.11 1.07 .75 .869 2.32 .92 .66 .740 3.48 1.21 .60 .709 3.10 1.26 .55 .618 3.04 1.32 .70 .842 2.58 1.12 .60 .679 2.31 1.13 .62 .804 2.75 1.06 .62 .567 2.77 1.15 .61 .727 4.00 .76 .55 .704 4.04 .86 .58 .599 4.11 .91 .60 .658 4.31 .84 .64 .765 Note. UI = Utilitarian Incentives; SI = Solidary Incentives; PI = Purposive Incentives; II = Informative Incentives. exogenous variables (Mueller, 1996; Schutz, Eom, Smoll, & Smith, 1994). The coefficients of Θ∆ revealed by the variance/covariance matrix of measurement errors ranged from .15 to .56 (M = .39); free parameters were in a diagonal line with all off-diagonal elements fixed to zero. The coefficients indicated that a reasonable amount of variance was associated with measurement errors (Motl & Conroy, 2000; Mueller, 1996). 122 Chen Figure 2 — The diagram shows the relationships of four latent variables with 14 indicators in CFA for the validation sample: Utilitarian Incentives (UI), Solidary Incentives (SI), Purposive Incentives (PI), and Informative Incentives (II). Θ∆ = Theta Delta, ΛΧ = Lambda Chi, Latent V = Latent Variables, Phi = Inter-factor Correlation Coefficients. The Phi values of paired latent variables, ranging from .36 to .67 (M = .55), indicated that two pairs of coefficients (SI with UI = .66; SI with PI = .67) were relatively high (see Figure 2). The variance-extracted measures, which reflect overall variance contributed by the indicators (Hair et al., 1998), were employed to test the four latent variables. The coefficients (UI = .66, SI = .62, PI = .57, and II = .58) were all satisfactory (above the .50 criterion) confirming that “the indicators are truly representative of the latent construct” (Hair et al., 1998, p. 612). The means, standard deviations, and the values for ΛΧ and Θ∆ of Sample B are shown in Table 3. To interpret the output of CFA (see Table 3 and 4), three sets of measures were applied. The first, absolute measures, included a likelihood ratio Χ2 (231.23, p < .001) that was significant and is often affected by sample size (Boomsma, 2000; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996b); a Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI, .96) that was higher than the .90 criterion; and a Root-Mean-Square Residual (RMSR, .048) that was acceptable, indicating that an average residual correlation was below the Membership Incentives 123 Table 3 Means, Standard Deviations, ΛΧ, and Θ∆ of CFA for Validation Sample (n =207) Items U1 U2 U3 S4 S5 S6 P7 P8 P9 P10 I11 I12 I13 I14 Table 4 Χ2 231. 23 M SD ΛΧ Θ∆ 2.41 2.11 2.37 3.53 3.14 3.12 2.60 2.37 2.76 2.80 3.92 4.02 4.07 4.26 .89 .94 .89 1.14 1.10 1.17 1.08 1.14 1.02 1.00 .70 .79 .92 .93 .85 .83 .76 .75 .68 .92 .80 .79 .78 .62 .66 .69 .94 .73 .28 .31 .42 .44 .54 .15 .35 .37 .39 .62 .56 .53 .12 .47 Goodness-of-Fit Indexes of CFA for Validation Sample (n = 207) df Χ2/df RMSR AGFI GFI NNFI IFI CFI 71 3.25 .048 .940 .960 .920 .940 .940 limit of .05 (Bollen, 1989; Byrne, 1998; Hu & Bentler, 1999). The second set of measures, parsimonious fit measures, contained an Adjusted-Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI, .94) that was higher than the recommended level of .90 and a Normed Χ2 (Χ2/df, 3.25) that might need improvement. This index is not a proper indicator, however, and other fit indexes should be used (Byrne, 1998; Hair et al., 1998). Therefore, a third set of measures, incremental fit measures, were used. These measures were determined by comparing incremental fit of the model to a null model and were mainly interpreted from the Non-Normed-Fit Index (NNFI, .92); this was deemed satisfactory (Bollen, 1989; Hair et al., 1998). The Incremental-Fit Index (IFI, .94) and Comparative-Fit Index (CFI, .94) were also evaluated because these indexes are influenced least by the sample size 124 Chen and the normality of data (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Hutchinson & Olmos, 1998). Both values met the requirement. It should be noted that even if the fit indexes were less than perfect, the results of CFA were acceptable overall and provided support to the factorial validity of MIS. Internal consistency reliabilities. The internal consistency reliabilities of the MIS factors were tested using alpha reliability (Cronbach, 1951) and composite reliability (Hair et el., 1998). As shown in Table 5, alpha coefficients for the four subscales ranged from .704 to .733 for Sample A, .684 to .735 for Sample B (marginally accepted; Hair et al., 1998), and .714 to .729 for the multiple sample. The composite-reliability estimates of MIS factors were .830 to .854 for Sample B and .814 to .857 for the multiple sample. All findings of the two tests for the three samples exceeded the .70 standard (Hair et al., 1998; Stevens, 1996); that provided adequate support for the internal consistency reliabilities of the MIS factors. Comparing the mean scores of Samples A and B, items U1, U3, S4, P10, and I14 were scored higher than the rest of the items in their respective factors (see underlined values in Tables 2 and 3). The mean scores of the four factors displayed a similar trend (see Figure 3) in that Informative Incentives received the highest ratings (M = 4.12 and 4.07 for Sample A and B, respectively), followed by Solidary Incentives (M = 3.21 and 3.23 for Sample A and B, respectively), and Purposive Incentives (M = 2.60 and 2.63 for Sample A and B, respectively). Utilitarian Incentives had the lowest scores (M = 2.25 and 2.28 for Sample A and B, respectively) as rated by the participants. Discussion The results of this study provided support for the validity of 14 important incentive items. These incentive items, along with their respective factors, were grounded Table 5 Alpha Reliabilities and Composite Reliabilities of 4 Factors for Calibration Sample A (n = 208), Validation Sample B (n = 207), and Multiple Sample (N = 415) Variable Factors Utilitarian Incentives(UI) Solidary Incentives (SI) Purposive Incentives (PI) Informative Incentives (II) Sample A Sample B Multiple Sample Alpha Reliabilities Alpha Reliabilities (Composite Reliabilities) Alpha Reliabilities (Composite Reliabilities) .704 .710 .732 .733 .701 (.854) .684 (.830) .735 (.837) .719 (.844) .714 (.857) .716 (.814) .729 (.845) .717 (.840) Membership Incentives 125 Figure 3 — Mean scores of four incentive factors of samples A and B. in a plausible conceptual framework and supported by systematic research procedures. The items were also based on distinctive social features and evaluated by professionals who belonged to the types of associations targeted by the study. The findings presented quantitative evidence to support the factorial validity and internal consistency reliability of the MIS as an instrument to measure the importance of expected incentives to organizational members. In addition, the conceptual model illustrating individuals’ decisions about participation was confirmed statistically using the input of the members of athletics-related professional associations. Even though this four-factor model has stronger statistical support compared with the previous studies, the psychometric aspect of the MIS might be less than perfect. For instance, there have been inconsistent reports regarding the cutoff points for Root-Mean-Square Residual (RMSR) in SEM references. Values between .05 and .08 for RMSR are suggested as acceptable by some SEM literature (e.g., Byrne, 1998; Hu & Bentler, 1999) in contrast to other reports (e.g., Hair et al., 1998) that suggest values lower than .05 as appropriate criteria . Further investigation to compare the indexes revealed by variations in sample size, normality of data, and applied methods (ML, WLS) would be meaningful (Boomsma, 2000; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Because relatively higher correlation coefficients (see Figure 2) were found between solidary incentives (SI) and utilitarian incentives (UI), and with purposive incentives (PI) exceeding 40% of contributed variances (Φ2 = .45 and .43), the weak independency of the factors called attention to the need for further research. Because the specified four factors all could affect potential members’ decisions about participation to some degree, it is not surprising that factors were significantly correlated with each other in the oblique situations of EFA and CFA. A possible explanation would be that both SI and 126 Chen PI measure the psychological dimensions that are characterized as intangible rewards. The shared variance between PI and UI does warn researchers that maintaining high-level factor independence for the advancement of the psychometric measure would be a challenge because the issue has often been evidenced in the development of Likert scales (Hair et al., 1998; Motl & Conroy, 2000; 1996; Schutz et al., 1994). It is not surprising that utilitarian incentives were the least important factor perceived by the participants (see Figure 3). This is consistent with the work of Clarke et al. (1978), who found that the members of nonprofits often undervalue the availability of patronage and privelege but pursue other intangible interests in accord with their political ideology and satisfying to their sense of self-esteem. The supported finding was also presented by Caldwell and Andereck (1994), who concluded that the members of recreation-related voluntary associations considered utilitarian benefits to be unimportant incentives with the exception of members whose incomes were low. Item U2 (obtain benefit of membership [discounts and programs]) had the lowest mean, which indicated that these benefits did not have a significant effect on individuals’ decisions about participation. Because most members of athletics-related professional associations were well established (mean years as members were 11.08 for coaches and 9.60 for administrators), this type of incentive was not the sole force motivating them to become members. Purposive incentives were also scored low by participants. This is the opposite of previous findings (Caldwell & Andereck, 1994; Clarke et al., 1978; Farrell et al., 1998; Mondo, 1992), which indicate, based on members evaluations, that purposive incentives were a primary reason for collective action. Most coaches’ associations, however, have generally made little use of their political power to lobby the legislature. Members might be more motivated to achieve individual goals and make occupational progress when compared with members of other voluntary societies. This could also be deduced from the higher score of item P10 (appeal to social values and occupational standards). Viewing coaches as managers of sport teams and taking into consideration that administrators already hold leadership positions, individuals’ reasons for being members of an organization could be attributed to their pursuit of career prestige and professional identity rather than the need to exercise leadership and power in voluntary associations. Solidary incentives surpassed utilitarian incentives and purposive incentives in average scores given by members of athletics-related associations (see Figure 3); this is identical with the findings of Caldwell and Andereck (1994), Farrell et al. (1998), and Knoke (1988). Perhaps the participants in this study shared solidary motives in common with the members of recreation-related societies and their parallel voluntary associations that participated in the earlier studies. Both groups of participants could also view emotional attachment to groups and friendship as more attractive motives for membership. Organizations could therefore have provided their members more opportunities for socialization. Item S4 (gain affinitive feelings from organizational activities) had the highest mean within the factor indicating that this incentive was truly applied. The affinitive feelings of Membership Incentives 127 members could be facilitated through associational gatherings such as alumni meetings or social events at annual conventions. Solidary incentives were rated lower in the studies of Clarke et al. (1978) and Mondo (1992) probably because the members of political parties and social-interest organizations (the participants in these studies) were more politically or materially oriented. It is interesting to note that informative incentives were rated as the most important factor, particularly item I14 (learn about future trends through networking). This result, however, is inconsistent with the finding of Knoke (1988), who reported that information incentives were not beneficial enough to the members in either highly or less politically oriented organizations. A possible explanation would be that the athletics-related professional associations might have provided more services relating to valuable information that actually benefited their members. The members likely appreciate well-organized and timely information that supports personal growth, financial success, and professional achievement. It is the nature of informative incentives to combine both tangible and intangible benefits to optimize the homogenous preferences and expectations of most members in the athletics-related professional associations. In conclusion, informative incentives should definitely receive the highest priority as organizational inducements expected by individuals in the athleticsrelated professional associations. Solidary incentives are useful to retain current membership (Rotherberg, 1988), purposive incentives are helpful to recruit normative members, and utilitarian incentives might be properly inserted as supplements to reward members who contribute to the association or to satisfy members who are materially oriented. It is the combined nature of associational similarities and guild distinctivities to suggest that heterogeneous incentives deserve to be applied to satisfy the wants, needs, and desires of the members. Therefore, a specification is presented, based on the conceptual model and the findings of this study, that represents a conclusive notion of the members’ decisions about participation: D = p(UI + SI + PI + II) where the decisions (D) of professionals to participate are affected by the probability (p) of inducement effects made by the associations, multiplied by the summed degrees of individuals’ expectations toward the four factors (utilitarian incentives [UI], solidary incentives [SI], purposive incentives [PI], and informative incentives [II]). The higher the summed degrees of disposition of the factors from professionals, the more likely they would decide to become members when the probability of the inducement effects from the association remains constant. On the other hand, the higher the inducement effects produced by the organization, the more likely an individual would decide to engage in the organization when the total degrees of the individual’s expectations toward the incentives remains unchanged. Hence, the individual’s preferences and the association’s goals are not always integrated into the organizational marketplace. So the incentive systems of any athletics-related professional association would be continually formed and reformed in a mutual communication between the associations and their members (Knoke, 128 Chen 1988). The 14-item MIS with acceptable factorial (construct) validity and internal consistency reliability would be beneficial to both practitioners and researchers. Top-level administrators could refer to this study in order to upgrade their incentive systems and to adjust organizational strategies for membership retention and organizational expansion. In addition, marketing managers who are responsible for promoting associational activities might use the MIS to gather relative information about critical incentives needed by their customers (members) and the factors affecting the behavior of members in a targeted segment of the market. Moreover, the members of associations would be interested in the MIS to better comprehend their own motivational patterns and to evaluate the incentives offered by their associations when deciding to continue membership. Additionally, interested researchers could use the MIS as a measurement tool or a research reference for studying the direction of organizational inducement or to extend their analytical efforts to other incentive systems such as academics-related associations (e.g., North American Society for Sport Management). The entire scale can be used to assess members’ perceptions toward the incentives used by their respective guilds. Associated with a demographic information sheet, the MIS can be used to collect data to generate means or mean vectors for any designed independent variables (e.g., gender, income level) with proper statistical analyses (e.g., t-test, multivariate analysis of variance [MANOVA]) and to determine the significant differences between or among defined groups. Adopting a particular factor or suitable items of the MIS into an existing incentive inventory could be used as a method for measuring specific domains of members’ motives in a particular association. Computing the subtotal of the means of MIS factors or the items rated by the participants and interpreting the ranking orders of means or total scores could be an additional way for practitioners to decide what necessary adjustment should be made to meet the expectations of their members. Several caveats could be added to this article. Because the 14 items might be limited in the coverage of all potential motivational patterns, the MIS could probably be further improved. For example, “represent my career characteristics” was in the preliminary draft (see Note 2, d) for solidary incentives; it might be conceptually sound, but it failed in the factor analysis or in a data-driven context (Boomsma, 2000). More items or factors could be further developed because incentive systems can change as members’ interests or associations’ foci shift. Also, the factor of informative incentives received high scores from respondents, reflecting an extreme effect of response. The items of this factor were probably designed based on the input of active members and exactly matched the expectations of individuals to the benefits used as inducements in their systems of associations. This limitation could be reexamined in further studies. Moreover, because the participants involved in this study represented only college level professionals, the MIS could be used to test the membership incentives for other populations at a similar level because of the generalizability of the instrument. Additionally, the capacity for predicting the likelihood of joining and staying in associations was not emphasized in this study because the MIS was Membership Incentives 129 designed to measure the perceptions of individuals toward specific membership incentives. Thus, there is an opportunity for future research to identify the participation levels of members. Further research attention also needs to be directed toward testing different samples (Schutz et al., 1994) using the MIS and comparing the results with this report. The possibility of discovering different preferences regarding membership incentives using various organizational marketing segments as independent variables (e.g., status, experience, division level) calls for further investigation. Another important research topic would be to uncover the connection between the demand for incentives from the members and the supply of inducements offered by organizations in the context of athletics-related professional associations. In addition, it should be meaningful to administer a case study of a particular association, such as National Association for Collegiate Directors of Athletics or Intercollegiate Women’s Lacrosse Coaches Association, to discover more details of how the organization allocates its acquired resources from the incentive system and which motivational factors play a more critical role in increasing the enrollment rates of the association. Researchers are encouraged to provide more varied findings beyond this initial report so that managers of associations that would use multidimensional incentives to motivate their members and accumulate knowledge of additional means to ensure growth of athletics-related professional associations. References Bargh, A.J. (2002). Consumer judgment, behavior, and motivation. The Journal of Consumer Research, 29(2), 280-285. Bollen, K.A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley. Boomsma, A. (2000). Reporting analyses of covariance structures. Structural Equation Modeling, 7(3), 461-483. Byrne, B.M. (1998). Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Caldwell, L.L., & Andereck, K.L. (1994). Motives for initiating and continuing membership in recreation-related association. Leisure Studies, 16(1), 33-44. Clarke, H.D., Price, R.G., Stewart, M.C., & Krause, R. (1978). Motivational patterns and differential participation in a Canadian party: The Ontario Liberals. American Journal of Political Science, 22(1), 131-150. Clark, P.B., & Wilson, J.Q. (1961). Incentive systems: A theory of organization. Administrative Science Quarterly, 6(2), 129-166. Cronbach, L.J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297-334. Farrell, J.M., Johnston, M.E., & Twynam, G.D. (1998). Volunteer motivation, satisfaction, and management at an elite sporting competition. Journal of Sport Management, 12(3), 288-300. Gordon, C.W., & Babchuk, N. (1959). A typology of voluntary associations. American Sociological Review, 24(1), 22-29. Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L., & Black, W.C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Hawkins, D., Best, R.J., & Coney, K.A. (1986). Consumer behavior: Implications for mar- 130 Chen keting strategy (3rd ed). Plano, TX: Business Publications. Hu, L., & Bentler, P.M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1-55. Hutchinson, S., & Olmos. A. (1998). Behavior of descriptive fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis using ordered categorical data. Structural Equation Modeling, 5(4), 344-364. Jöreskog, K., & Sörbom, D. (1996a). PRELIS 2: User’s reference guide. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International. Jöreskog, K., & Sörbom, D. (1996b). LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International. Knoke, D. (1988). Incentives in collective action organization. American Sociological Review, 53(4), 311-329. Knoke, D., & Prensky, D. (1984). What relevance do organization theories have for voluntary associations? Social Science Quarterly, 65(1), 3-20. Knoke, D., & Wood, J.R. (1981). Organized for action: Commitment in voluntary associations. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Knoke, D., & Wright-Isak, C. (1982). Individual motives and organizational incentive systems. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 1(3), 209-254. Mondo, P.A. (1992). Interest group: Case and characteristics. Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall. Motl, R.W., & Conroy, D.E. (2000). Confirmatory factor analysis of the physical self-efficacy scale with a college-aged sample of men and women. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 4(1), 13-27. Mueller, R.O. (1996). Basic principles of structural equation modeling: An introduction to LISREL and EQS. New York: Springer. National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics. (1998a). (men’s and women’s editions). Cleveland, OH: Author. Olson, M. (1971). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Rotherberg, L.S. (1988). Organizational maintenance and the retention decision in groups. American Political Science Review, 82(4), 1137-1149. Schutz, R.W., Eom, H.J., Smoll, F.L., & Smith, R.E. (1994). Examination of the factorial validity of the group environment questionnaire. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 65(3), 226-236. Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS). (1999). SPSS for windows: Advanced statistics, release 9.0. Chicago, IL: SPSS. Sternthal, B., & Craig, C.S. (1982). Consumer behavior: An information processing perspective. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Stevens, J. (1996). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Thomas, W.J. (1998). Motivational research: Explaining why consumers behave the way they do. Direct Marketing, 60(12), 54-57. Weisbrod, B.A. (1998). Institutional form and organizational behavior. In W.W. Powell & E.S. Clemens (Eds.), Private action and the public good (pp. 69-84). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Notes 1 The participants involved in this study were the active members from 15 profes- Membership Incentives 131 sional associations including: National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics (NACDA); American Football Coaches Association (AFCA); American Baseball Coaches Association (ABCA); Women’s Basketball Coaches Association (WBCA); National Association of Basketball Coaches (NABC); American Volleyball Coaches Association (AVCA); National Field Hockey Coaches Association (NFHCA); National Soccer Coaches Association (NSCA); National Fastpitch Coaches Association (NFCA); Intercollegiate Women’s Lacrosse Coaches Association (IWLCA); Intercollegiate Tennis Association (ITA); National Wrestling Coaches Association (NWCA); National Collegiate Gymnastics Association (NCGA); College Swimming Coaches Association of America (CSCAA); and National Association for Golf Coaches and Educators (NAGCE). 2 The following six problematic items were dropped in the item reduction of EFA: (a) have business opportunities at annual conventions (in UI), (b) assist to improve my economic condition or promotion (in UI), (c) discuss with my colleagues for current problems in team management (in SI), (d) represent my career characteristics (in SI), (e) demonstrate my achievement (in PI), and (f) present my studies and new coaching methods (in II).