Probably Probable Cause

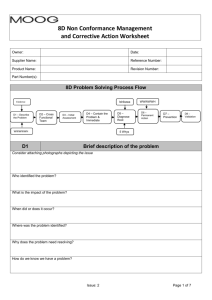

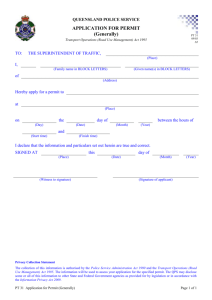

advertisement