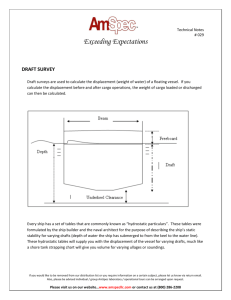

Cargo Claims and Recoveries

advertisement