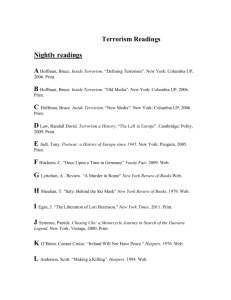

The Mind of the Terrorist: A Review and Critique of Psychological

advertisement