imperialism and the practising monopoly

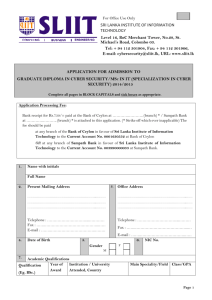

advertisement