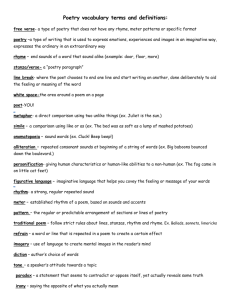

More Than Rhyme: Poetry Fundamentals

advertisement