SURVEY OF WEST VIRGINIA PRIVACY AND RELATED CLAIMS

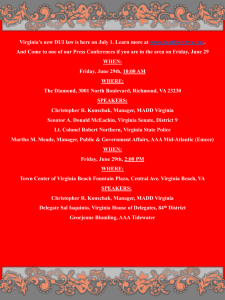

advertisement