http://leav-www.army.mil/fmso/documents/santa

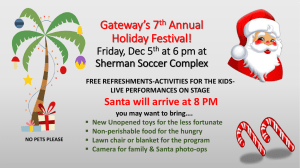

advertisement