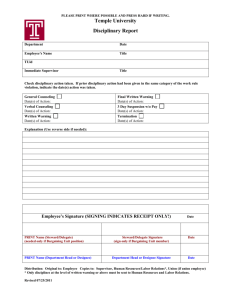

Management of Poor Performance: A

advertisement