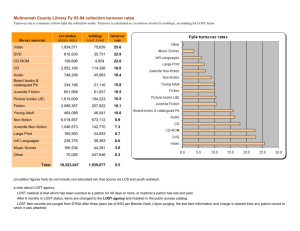

Meaning and Measurement of Turnover: Comparison of

advertisement