r1 Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis/dissertation has been

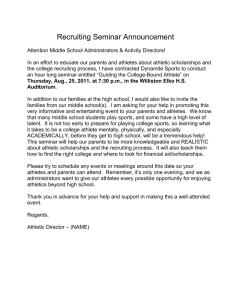

advertisement