Mathematica - Department of Mathematics & Statistics

advertisement

Math 421 Wolfram Mathematica

Introduction

Downloading

Mathematica is available for free for UMASS undergraduate and graduate students.

To download Mathematica:

1. Navigate to the UMASS OIT website at www.it.umass.edu

2. Click the Software button

3. Scroll down and find the Sciences, Statistics and Mathematics section

4. Locate the program Mathematica, and click on the link that says “Students”

5. On the next page you will find specific directions to download Mathematica

6. Long story short, click the link for the Mathematica Activation Key Request Form

7. Create an ID on Wolfram.com, using your UMASS Email address

NOTE: You must use your UMASS email address, so that wolfram recognizes you are entitled

to a free activation key.

8. Fill out the form on the next page, and Wolfram will send an activation key to your email

9. Download Mathematica, and fill in the activation key that was sent to your email

10. Start Mathematica, and select “new notebook” which is the file type Mathematica uses

11. ENJOY MATHEMATICA!

Cell Basics

Subsection

Subsubsection

Text

Input and Output

and Input Output

Evaluation Order

Cells evaluate in the order you tell them to evaluate in.

% gets the last evaluated thing.

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

2

Mathematica Presentation.nb

n

n

x ⅆ x

0

n=3

Clear[n]

%

Palettes

Used to help typeset things. Such as x20

Useful keyboard shortcuts and escape sequences

esc ii esc: ⅈ

esc ee esc: ⅇ

esc p esc: π

control /:

3

4

control ^: 54

command 1: Title

command 4: Section

command 5: Subsection

command 6: Subsubsection

command 7: Text cell

command 9: Input cell

shift enter: evaluate cell

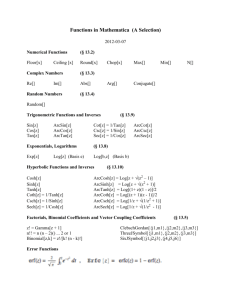

Useful Functions and Things

There are many, many more functions, but these are some of the ones I find myself using most often.

Often function names are somewhat intuitive, but when in doubt: Google.

A word of caution

Mathematica tries to solve things as accurately as possible, compare

12 345.12 345.

and

12 34512 345

Crashing Mathematica by not using decimals is pretty easy. 123 456 789123 456 789 was too much.

(Tetration and iterated functions are also dangerous.)

Simplify

I find this to be one of the most useful functions.

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

Mathematica Presentation.nb

? Simplify

Simplify[expr] performsa sequenceof algebraicand othertransformations

on expr and returnsthe simplestf ormit finds.

Simplify[expr, assum] doessimplification

u singassumptions

. %

Also look into

In[916]:=

? Refine

? Assuming

Refine[expr, assum] givesthe formof expr thatwouldbe obtainedif

symbolsin it werereplacedby explicitn umericale xpressionssatisfyingthe assumptionsassum.

Refine[expr] uses defaultassumptionss pecifiedby any enclosingAssumingconstructs

. %

Assuming[assum, expr] evaluatesexpr withassum appendedto $Assumptions

, so thatassum is

includedin the defaultassumptionsu sedby functionssuchas Refine, Simplify, and Integrate

. %

In[918]:=

Simplify[Cos[k Pi] ^ m, Element[k, Integers], Assumptions → Mod[m, 2] ⩵ 0]

Assuming[x > 0, Simplify[Sqrt[x ^ 2 y ^ 2], y < 0]]

Out[918]=

1

Out[919]=

-− x y

Solve

Solves things.

? Solve

Solve[expr, vars] attemptsto solvethe systemexpr of equationsor inequalitiesfor the variablesvars.

Solve[expr, vars, dom] solvesoverthe domaindom. Commonchoicesof dom are Reals, Integers, and Complexes

. %

Solve13 x4 -− 2 x3 + 4 x -− 9 ⩵ 0, x

% /∕/∕ N

(Note spaces between variables below)

Solvea x3 + b x2 + c x + d ⩵ 0, x

Plot

Used for plotting graphs

? Plot

? Plot3D

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

3

4

Mathematica Presentation.nb

Plot[ f , {x, xmin , xmax }] generatesa plotof f as a functionof x fromxmin to xmax .

Plot[{ f1 , f2 , …}, {x, xmin , xmax }] plotsseveralfunctionsfi .

Plot[…, {x} ∈ reg] takesthe variablex to be in the geometricregionreg. %

Plot3D[ f , {x, xmin , xmax }, {y, ymin , ymax }] generatesa three-−dimensionalplotof f as a functionof x and y.

Plot3D[{ f1 , f2 , …}, {x, xmin , xmax }, {y, ymin , ymax }] plotsseveralfunctions

.

Plot3D[…, {x, y} ∈ reg] takesvariables{x, y} to be in the geometricregionreg. %

PlotSin[x], x, x -−

x -−

x3

+

3!

x5

5!

-−

x7

7!

x3

3!

, x -−

, x + -−

x3

3!

+

x3

3!

x5

-−

5!

+

x5

5!

x7

7!

+

,

x9

9!

, {x, 0, 2 π}

8

6

4

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

-−2

-−4

-−6

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

Mathematica Presentation.nb

fx1 = x;

fx3 = x -−

x3

;

3!

x3

x5

fx5 = x + -−

+

;

3! 5!

x3

x5

x7

fx7 = x -−

+

-−

;

3! 5! 7!

x3

x5

x7

x9

fx9 = x -−

+

-−

+

;

3! 5! 7! 9!

x3

x5

x7

x9

x11

fx11 = x -−

+

-−

+

-−

;

3 ! 5 ! 7 ! 9 ! 11 !

x3

x5

x7

x9

x11

x13

fx13 = x -−

+

-−

+

-−

+

;

3 ! 5 ! 7 ! 9 ! 11 ! 13 !

Plot[{Sin[x], fx1, fx3, fx5, fx7, fx9, fx11, fx13},

{x, 0, 2 π}, PlotRange → {-− 2, 2}, PlotLegends → "Expressions"]

ClearAll[fx1, fx3, fx5, fx7, fx9, fx11, fx13]

2

sin(x)

fx1

1

fx3

fx5

1

2

3

4

5

6

fx7

fx9

fx11

-−1

fx13

-−2

Plot3D[Sin[x + y ^ 2], {x, -− 3, 3}, {y, -− 2, 2}]

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

5

6

Mathematica Presentation.nb

Manipulate

I actually hadn’t used this before, but I felt that showing this off would be useful.

? Manipulate

Manipulate

[expr, {u, umin , umax }] generatesa

versionof expr withcontrolsaddedto allowinteractivemanipulationo f the valueof u.

Manipulate

[expr, {u, umin , umax , du}] allowsthe valueof u to vary betweenumin and umax in stepsdu.

Manipulate

[expr, {{u, uinit }, umin , umax , …}] takesthe initialvalueof u to be uinit .

Manipulate

[expr, {{u, uinit , ulbl }, …}] labelsthe controlsfor u withulbl .

Manipulate

[expr, {u, {u1 , u2 , …}}] allowsu to takeon discretevaluesu1 , u2 , ….

Manipulate

[expr, {u, …}, {v, …}, …] providescontrolsto manipulateeachof the u, v, ….

Manipulate

[expr, cu → {u, …}, cv → {v, …}, …] linksthe controlsto the specifiedcontrollerso n an externald evice. %

Manipulate[n, {n, 0, 25}]

n

9.65

Manipulate[Factor[x ^ n + 1], {n, 1, 100, 1, Appearance → "Labeled"}]

n

1

1+x

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

Mathematica Presentation.nb

ManipulatePlota x3 + b x2 + c x + d, {x, -− 5, 5}, PlotRange → {-− 100, 100},

{a, -− 2, 2, Appearance → "Labeled"}, {b, -− 5, 5, Appearance → "Labeled"},

{c, -− 10, 10, Appearance → "Labeled"}, {d, -− 50, 50, Appearance → "Labeled"}

a

0.

b

0.02

c

0.

d

0.

100

50

-−4

2

-−2

4

-−50

-−100

Matrices

I gather in the olden day matrices had to be entered as something akin to array of array, but we have

fancy typesetting now. The operation notations are a bit odd though.

1 2 3

4 5 6

7 8 9

2

+

1 2 3

4 5 6

7 8 9

1 2 3

4 5 6

7 8 9

2 2 2

2 5 2

2 2 2

1 2 3

4 5 6

7 8 9

1 2 3

4 5 6

7 8 9

3

ⅇ

1 2 3

4 5 6 . π

7 8 9

ⅈ

1 2 3

MatrixPower 4 5 6 , 3

7 8 9

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

7

8

Mathematica Presentation.nb

1 2 3

4 5 6

7 8 9

!

1 2 3

Det 4 5 6

7 8 1

1 2 3

Inverse 4 5 6

7 8 1

The spellchecker (at does exist)

(Under the edit menu)

Complex Analysis

Basics

Inputting a complex variable in Mathematica is a simple as writing it on a piece of paper. Simply entering a complex variable such as “3 + i4” or “3 + 4i” Mathematica will automatically recognize it as a

complex variable.

3+4I

3 + 4 ⅈ

Arithmetic Operations

Performing arithmetic on complex variables is just as simple. For example:

(3 + 4 I) + (3 + 4 I)

6 + 8 ⅈ

This works for all simple arithmetic operations, even division:

(3 + 4 I) -− (2 + 2 I)

1 + 2 ⅈ

(1 + I) (1 -− 3 I)

4 -− 2 ⅈ

(4 -− 2 I) /∕ (1 -− 3 I)

1 + ⅈ

Special Operations/Functions

Mathematica also has some built in functions to evaluate complex numbers:

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

Mathematica Presentation.nb

9

Re[2 + 3 I]

Im[2 + 3 I]

ReIm[2 + 3 I]

Abs[2 + 3 I]

Arg[2 + 3 I]

AbsArg[2 + 3 I]

Sign[2 + 3 I]

Conjugate[2 + 3 I]

d = ComplexExpand[Sin[2 + 3 I]]

c = TrigToExp[d]

ExpToTrig[c]

Mathematica is a very powerful tool, it makes operating on complex numbers quite simple, and can

express them in whatever form you would like. The syntax may take a little getting used to, but it opens

the door to some incredible applications.

Plotting Imaginary Transformations

Old versions

This can be done with Parametric plots.

The below example is pretty viciously hard-coded. And is specifically the mapping w = z2 . The lines are

hard coded into the first graph and then the values are substituted into

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

10

Mathematica Presentation.nb

ParametricPlot[{{x, 1}, {1, y}, {x, 2}, {2, y}, {x, 3}, {3, y}}, {x, -− 5, 5}, {y, -− 5, 5}]

ParametricPlotx2 -− 12 , 2 x, 12 -− y2 , 2 y, x2 -− 22 , 4 x,

22 -− y2 , 4 y, x2 -− 32 , 6 x, 32 -− y2 , 6 y, {x, -− 5, 5}, {y, -− 5, 5}

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

Mathematica Presentation.nb

Another cunning plan....foiled

z = x + ⅈ y;(*⋆semicolon supresses output*⋆)

w = z2 ;

Table[ParametricPlot[{{Re[z], i}, {i, Im[z]}}, {x, -− 7, 7}, {y, -− 7, 7}],

{i, {1, 2, 3, 4}}]

TableParametricPlotRex + ⅈ i2 , Imx + ⅈ i2 , Rei + ⅈ y2 , Imi + ⅈ y2 ,

{x, -− 7, 7}, {y, -− 7, 7}, {i, {1, 2, 3, 4}}

ClearAll[

z,

w]

,

,

,

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

11

12

Mathematica Presentation.nb

,

,

,

Successes

This can be done with parametric plots, but there are some limitations: a finite domain and imperfect

sampling quality.

z[x_, y_] := Return[x + y ⅈ];

w[u_, v_] := Return(z[u, v])2 ;

{Show[Table[ParametricPlot[{{Re[z[a, i]], Im[z[a, i]]}, {Re[z[i, b]], Im[z[i, b]]}},

{a, -− 5, 5}, {b, -− 5, 5}], {i, {1, 2, 3, 4}}]],

Show[Table[ParametricPlot[{{Re[w[a, i]], Im[w[a, i]]}, {Re[w[i, b]], Im[w[i, b]]}},

{a, -− 5, 5}, {b, -− 5, 5}], {i, {1, 2, 3, 4}}], PlotRange → {-− 20, 20}]}

ClearAll[

z,

w]

,

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition

Mathematica Presentation.nb

13

z[x_, y_] := Return[x + y ⅈ];

w[u_, v_] := Return(z[u, v])-−1 ;

{Show[Table[ParametricPlot[{{Re[z[a, i]], Im[z[a, i]]}, {Re[z[i, b]], Im[z[i, b]]}},

{a, -− 10, 10}, {b, -− 10, 10}], {i, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}}]],

Show[Table[ParametricPlot[{{Re[w[a, i]], Im[w[a, i]]}, {Re[w[i, b]], Im[w[i, b]]}},

{a, -− 10, 10}, {b, -− 10, 10}], {i, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}}]]}

ClearAll[

z,

w]

,

Printed by Wolfram Mathematica Student Edition