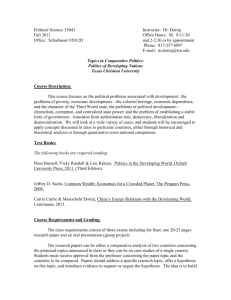

Syllabus

advertisement

Econ 40970 Modern European Economic History John Lovett Econ 40970: Modern European Economic History John Lovett, Fall 2015 The Basics Office: Scharbauer Hall, Room 4112, 817.257.6582 Office Hours: T, R: 10:00 – 12:00, or by appointment e-mail: j.lovett@tcu.edu Course Web Site: http://faculty.tcu.edu/jlovett , then Modern European Economic History Text: There is no assigned text. You will, however, have lots of readings that are either on reserve at the library or journal articles available on-line. You will need to copy these and keep them in a well-organized notebook of readings. Description of the Course This course investigates the economic development of Europe from (roughly) 1700 to 1960. The ECON 40970 course counts as an economics “Historical Context” course for Econ majors. It can alternatively serve as an economics elective for both Econ majors and minors. Our primary objectives in this course in this course are to: 1) Understand the importance of Europe’s (and later the world’s) transition from a preindustrial society to the first industrial society. The world has seen a lot of history. What makes Europe from 1700 to 1960 unique and important when compared to (for example) the history of Southwest Asia from 200 to 460 CE? Both places and periods are arguably important and offer exciting stories. Each has some lessons for today’s generation. Nonetheless, Europe from 1700 to 1960 is of particular interest to economists, and anyone living today, because it was the first instance in which rapid material changes became the norm. For all of human history prior to (roughly) 1700, the norm was for each generation, in material terms, to live in a very similar fashion to that of their parents. Today, the opposite is true. Change is the norm. A production process or material item that hasn’t changed since your parent’s time is unusual. As an experiment, think of ways our material living standard is the same as our parents and ways in which they differ? Which list is longer? This new era of change has many characteristics besides just an increased rate of change. Humanity’s energy use has increased by an order of magnitude as we turned from human, animal, and water energy to energy extracted from fossil fuels. Most production shifted from small enterprises to large scale factories. 2) Examine Colonization as a symptom and facilitator of Europe’s Economic Development. How important were the colonies in explaining Europe’s rise to economic hegemony? At the very least, colonization was a symptom of Europe’s economic rise. One cannot develop and sustain colonies without good naval technology and a robust market for colonial 1 Econ 40970 Modern European Economic History John Lovett goods. Did Europe’s colonies also make a significant contribution to European economic development? There are many theories arguing that colonization played a pivotal role in Europe’s industrialization. We will examine these theories. However, we will also find that the quantitative evidence supporting many of these theories is often quite weak. 4) Investigate Changes in Europe’s Social/Political Environment. In addition to changes in production technology, Europe underwent tremendous changes in her political systems. During the period of this course, Europe saw the rise of constitutional monarchy, representative governments, nationalism, populist movements, communism, fascism, etc. Most the “modern” political models were tried somewhere in Europe during the time period of this course. Why did Europe’s institutional environment evolve as it did? Which of these systems worked well at promoting economic well-being? Was the “choice” of a political/economic system open to change or did geography largely dictate each nation’s choice. 5) Look at the Important Role Energy Played in Europe’s Rise and later (relative) decline. It takes energy of some kind to produce everything we make from bread, to I-phones. In 1700, the energy used in production came from human and animal muscle, wind, water, and the yearly agricultural process. Estimates vary, but humans in advanced societies around the year 1700 used about 10,500 watt/hours of energy to produce their goods and services. Today, the average American still uses roughly the same amount of “pre-industrial” energy … plus another 85 million watt/hours of energy from electrical or fossil fuel sources. That’s more than an 8,000 fold increase! Dude! No wonder we can produce some much more than in the past! Where did this increase in energy use come from? In a word, coal. Further, Britain was far and away the early leader in coal production and use. To many, this is the single most important reason Britain led Europe into the Industrial Revolution. However, beginning in the early 1900s, oil began to replace coal as the most useable source of energy. While Europe had large reserves of coal, it is relatively short when it comes to oil. Perhaps the depletion of coal and the rise of oil played a large role in Europe’s relative decline. 6) Examine the many, may, Crises Europe Faced between (roughly) 1910 and 1960. While Western Europe may have led the world into this era of change, as is often the case, it’s hard to stay on top. Beginning (approximately) in the late 1800’s Europe lead over the rest of the world shrunk. Much of the first half of the 20th century was a time of crises for Europe. First came the devastation of World War I. This was followed by rampant political and social strife throughout most of Europe. The specter of communism took hold in Russia while Germany and Italy went fascist. Then came the Great Depression, continued unrest, and the horrors of World War II, the loss of colonial empires, etc. By the end of World War II, it is easy to argue that Europe had fallen from its former position of world leader. In recent decades, however, Europe seems to have climbed back to near the top of the Economic heap. Although the last 50 years are beyond the scope of this course, we will discern many lessons from Europe’s half-century of decline (1910 – 1960). 2 Econ 40970 Modern European Economic History John Lovett Grading. Possible points are shown at right. Course grades are assigned as shown below. A A92.5%+ 89.5%+ B+ B B86.5%+ 82.5%+ 79.5%+ CC+ C 76.5%+ 72.5%+ 69.5%+ D+ D D66.5%+ 62.5%+ 59.5%+ Possible Points Item Exams 1 – 3 3 x 100 = 300 + Final Exam 100 + Reading Notebook Checks 5 x 10 = 50 + Homework 4 x 25 = 100 + Participation (+100 to -90) 100* = Total = 750 Exams: Exams are generally half essay, half objective. I’ll give you questions to study (via the course website) as the course progresses. Reading Notebook Checks: I want you to physically have the assigned readings. State anti-stalking laws preclude me from determining this directly (sorry … very innapropriate humor). Instead, I will merely check periodically to see if you have all the readings. I’ll give you mor explicit directions later. The basics, however, are that you will need to get a 2” ring binder. In this folder you will keep your readings seperated by dividers. From time to time, I’ll check to see that everything is in there. Homeworks: You will have four homework assignments. Typically, in these you will use quantitative/graphical analysis to investigate the economic effects of various historical changes. For example, in two of these homeworks you will investigate the role falling shipping costs played in changing both the types of items produced for export and the overall level of competition.. 80 3, 90 6, 75 60 9, 60 15, 30 Participation Points 40 12, 45 20 18, 15 0 21, 0 -20 24, -15 27, -30 -40 30, -45 -60 33, -60 -80 36, -75 -100 0 5 10 15 20 25 Days Absent 3 30 35 39, -90 I will excuse an absence if: 1) you miss class for an official TCU (not fraternity or sorority) activity, medical emergency, etc. and, 2) you provide documentation or an e-mail from Campus Life. If an absence is excused, I drop it from both the numerator and the denominator. 100 1, 100 0, 100 Participation is based on attending class, being alert, and interacting in class. You start with 100 participation points. You can miss one day with no penalty. After that, each class you miss costs you 4 points unless it is excused (see next paragraph). The chart at righ shows participation points as a function of attendance. Please note that your participation score can be negative if you miss enough classes. This is akin to courses in which you lose a letter grade after X number of absences. 40 Econ 40970 Modern European Economic History John Lovett Classroom behavior such as showing up late, using your cell phone, disruptive conversations, shooting tranqulizer darts, unleashing rabid hyenas, etc., can also cost you participation points. Finally, I reserve the right to make minor changes to syllabus to facilitate a better student experience. Students With Disabilities Texas Christian University complies with the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 regarding students with disabilities. Eligible students seeking accommodations should contact the Coordinator of Student Disabilities Services in the Center for Academic Services located in Sadler Hall, 11. Accommodations are not retroactive, therefore, students should contact the Coordinator as soon as possible in the term for which they are seeking accommodations. Further information can be obtained from the Center for Academic Services, TCU Box 297710, Fort Worth, TX 76129, or at (817) 257-7486. Adequate time must be allowed to arrange accommodations and accommodations are not retroactive; therefore, students should contact the Coordinator as soon as possible in the academic term for which they are seeking accommodations. Each eligible student is responsible for presenting relevant, verifiable, professional documentation and/or assessment reports to the Coordinator. Guidelines for documentation may be found at http://www.acs.tcu.edu/disability_documentation.asp. Students with emergency medical information or needing special arrangements in case a building must be evacuated should discuss this information with their instructor/professor as soon as possible. Academic Misconduct Policy Don’t cheat or facilitate cheating! Do your own work, don’t plagiarize, etc. Definitions of academic misconduct, as well as possible sanctions for academic misconduct, can be found in the TCU Student Handbook. A “Procedures for Dealing With Academic Misconduct” can be found at the Department of Campus Life and the AddRan College Dean’s office. One of the best predictors of economic success for a nation is low levels of corruption. Both theory and empirical evidence strongly support this. Nations in which cheating, bribery, favoritism, and bending the rules is the main to get what you want are almost universally poor and underdeveloped. They also are usually rife with great social problems such as incredible inequality. Why am I telling you this now? Playing fair is not just a good thing in the moral sense. Playing fair is also good for society. In societies where breaking the rules is the norm, people often get their positions and contracts based on who is the best cheater, not who is the best at doing the job or making the product. If cheating is pervasive, your doctor is not one of the best at providing medical care. Instead, he or she is simply one of the best at cheating on exams, etc. If cheating is prevalent, the company building the bridges you drive over is not particularly good at building safe, low cost bridges. Instead, they build unsafe, over-priced bridges, but sure know how to bribe and cheat their way into contracts. The point is that a cultural acceptance of cheating is a major scourge for both academia any society. Accordingly, I will punish any incidents of academic dishonesty I discover. 4