Cocoa - Global Exchange

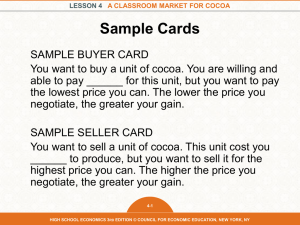

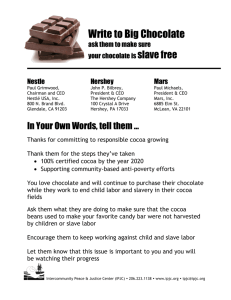

advertisement