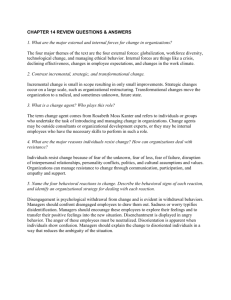

Leadership and Performance in Human Services Organizations

advertisement