Oxford University's First World War Poetry Digital Archive

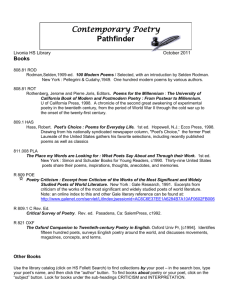

advertisement