Sport. Psychology - The Recovery Zone

Sport. Psycho logy

Christopher Si. Carr

The field o f sport and exercise psychology explores the relationship between psychological factors (e.g., cognition, affect) and optimal performance. Sport psychology is slowly becoming an integral aspect o f the holistic care of the sports medicine patient. The sports medicine specialist should have some knowledge regarding the various facets of sport and performance psychology, as many o f these skills are relevant to the care and management of an athletic population. For the puipose of this chapter, the areas of both "sport" and "performance" psychology will be discussed.

#$ % # $

is used in this chapter to represent the various environments under which mental skills enhancement can be useful.

#& # $ represents the use o f mental skills training within the sport and exercise domain. Many of the techniques utilized by elite athletes have had comparable successes with elite musicians, actors, and dancers. Therefore, the skills that are addressed in this chapter, although related in the sport environment, may be helpful for various forms of performance. The sports medicine professional can benefit his or her understanding o f the diversity o f performance issues and problems that may affect the patients by the material presented in this chapter.

Topics addressed in this chapter include a brief review o f the history and current issues o f sport psychology, a quick summary of "mental skills" training techniques, and a discussion o f specific performance concerns related to the injured athlete. If a sports medicine professional is to establish a "holistic" philosophy of care, an understanding of underlying psychological processes along with a model of care, is necessary.

HISTORY A N D CURRENT ISSUES

Sport psychology dates back to the turn of the twentieth century(Wiggins, 1984). The field o f sport psychology is a relatively young discipline, yet it has a history unrealized by most. The historical path of sport psychology is patchy at best with roots in both applied and academic sport psychology, which are primarily housed in physical educa- tion/kinesiology. Rarely is "sport" psychology recognized as a specialty within psychology departments.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, sport psychology had its beginning. It was Norman Triplett, who in

1897 conducted the first experiment in sport psychology by investigating the effect o f cyclists on one another's performance. After finding that young children performed better on a rote motor task in the presence of other children, he concluded that cyclists would usually perform better in the presence o f other cyclists. The results supported the hypothesis; when a cyclist performed with another cyclist on the track, they went faster than when they performed by themselves. Other studies taking place at about the same time include looking at motor behavior by exploring individual reaction times as well as how personality development was influenced by sport. However, none of these experiments and studies were directly applied to athletes or sporting realms (Wiggins, 1984).

Because the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) hired its first full-time sport psychologist in 1985, the applied realm o f sport psychology has continued to grow tremendously (die USOC now has four full-time licensed psychologists representing its sport psychology services).

Journals within the area o f sport psychology were published and Division 47 (Exercise and Sport Psychology) in the

American Psychological Association (APA) was established, for the first time in history recognizing the uniqueness offered to the field o f psychology in sport. In addition, the first time that teams were accompanied by a sport psychologist was during the 1988 Olympic Games. Other advancements in the field included the establishment of the Association for the Advancement of Applied Sport

Psychology (AAASP) in 1986 and the beginning o f the

Journal o f Sport Psychology in 1979. In 1991, as a

596 ACSM's Primary Care Sports Medicine • www.acsm.org

way to further advance this burgeoning field, the AAASP established criteria designating a "certified consultant" in the field o f sport psychology to improve the clarity and understanding of a sport psychologist.

The applied realm o f sport psychology has been growing rapidly in use and popularity during the 1990s. This use has not been limited to elite athletes such as those represented at the Olympic Games. Applied sport psychology is finding itself at the Olympic, professional, college, high school, and youth levels. Many well-known professional athletes in football, baseball, basketball, and golf have been sharing their beliefs in sport psychology as part o f a performance, along with physical and technical skills, that makes a complete athlete. Some collegiate athletic departments now employ full-time psychologists for their student athletes.

The amount of requests for sport psychology services at high school and elementary school levels and youth camps has grown tremendously in recent years.

Applied sport psychology covers all sports, not just those more visible, such as football, baseball, and basketball.

Sport psychology is being utilized and sought after for race car drivers, as well as in mountain biking, rowing, soccer, and rifle and pistol shooting. Many physicians, attorneys, and corporate executives are requesting sport psychology principles be applied to the "performances" in their respective settings. The applied possibilities in performance psychology seem almost endless.

Although the field has come far in the last 10 years, especially in the area o f applied sport psychology, it has not been without its controversies. Probably the largest debate in the field of sport psychology involves the question of what is a "sport psychologist" and who are able to identify themselves as such. Two primary groups identify themselves as sport psychologists, one from the academic side and the other from the applied side. The academicians and researchers in exercise and sport psychology and physical education are concerned with how an athlete can increase speed, motor control, and/or other physical capabilities to enhance performance. The sport psychologist in applied settings, on the other hand, has typically been concerned with the mental and emotional well-being of the athlete and utilizes psychological theory and concepts in the sport world.

In 1991, the AAASP identified requirements for being a

"certified consultant" in the field o f sport psychology as a step toward clarifying the training required to be a sport psychologist. Murphy (1995) summarizes the criteria as follows:

A doctoral degree

Knowledge of scientific and professional ethics and standards

Three courses in sport psychology (graduate level preferred; advanced techniques)

Courses in biomechanics or exercise physiology

Courses in the historical, philosophical, social, or motor behavior bases of sport

Course work in pathology and its assessment

Training in counseling (e.g., coursework, supervised practice)

Supervised experience with a qualified person in sport psychology

Knowledge of skills and techniques in sport or exercise

Courses in research design, statistics, and psychological assessment

Knowledge of the biological bases o f behavior

Knowledge of the cognitive-affective bases o f behavior

Knowledge of the social bases o f behavior

Knowledge of individual behavior

MENTAL SKILLS IN SP O R T

Many coaches and athletes attempt to put in a significant amount of physical practice to correct mistakes made during competition. Many times, however, the mistakes are due to mental breakdowns as opposed to physical or technical ones. In these cases the athlete needs to practice mental, not physical, skills. In the same way, physicians working in sports medicine facilities and/or with athletes sometimes forget or do not realize how mental skills can be used in their work.

Although coaches, athletes, and sports medicine physi cians agree that more than 80% o f the mistakes made in sport are mental, they still do not attempt to learn or teach mental skills that will assist athletes on the field or dur ing rehabilitation. First, sports medicine physicians' lack of knowledge about mental skills prevents them from us ing them in their work with athletes. Although physicians may tell their athletes to "just relax" as they go through rehabilitation of an injury, they do not provide them with the knowledge of how to do so. Second, mental skills in sport are often viewed as part o f an individual's personality and something that cannot be taught. Many physicians feel that injured athletes either have or do not have the mental toughness to progress through rehabilitation. Mental skills can be learned! Injured Olympic athletes report practicing mental training on a daily basis. Another reason why physi cians working with athletes might neglect mental training is because o f lack o f time. However, these skills can not only be learned, but they do not require an excessive amount of time.

The following section briefly discusses some o f the mental skills necessary for athletes to improve chances o f optimal performance in their sports, whether on the field or in the training room. These skills are the basics and much more depth and detail, than this chapter allows, is needed to completely explain and understand the power of the mind in sport.

G O A L SETTING

Goal setting is one of the primary mental skills used by athletes. In fact, this skill is helpful and even necessary

Chapter 36: Sport Psychology 597 to develop other mental skills. Csikszentmihalyi (5) discusses goal-setting as one o f the necessary components o f achieving a "flow" experience. He describes "flow" as an experience in which a person achieves peak performance.

Other terms used for this "flow" experience are "in the zone" and "playing unconscious."

It is not typically a problem to get athletes to identify goals. The difficulty comes in trying to help athletes set the right kind of goals—ones that provide direction, increase motivation, and guide them to achieving optimal performance. Athletes, and most people for that matter, do not need to be convinced that goals are important. They do, however, need instruction on setting goals and a program that works to achieve them.

It is demonstrated in the empirical research that goal setting can enhance recovery from injury. Research also demonstrates that certain types of goals are more effective in helping athletes achieve these goals. Several goal-setting principles have been identified that provide a strong base forbuildinga solid goal-setting program (seeTable 36.1).

1.

&%

Research illustrates that setting specific goals produces higher levels of performance than planning no goals at all or setting goals that are too broad. Yet many times physicians tell athletes to "do their best" or "give everything you have" regarding their recovery. Although these goals are admirable, they are not specific and do not help athletes move toward optimal performance. Goal-setting needs to be measurable and stated in behavioral terms. Instead of an athlete setting his or her goal to "get better," sport medicine physicians can help these injured athletes set a more appropriate goal such as "increasing leg press weight by 25% over the next 2 weeks."

2.

& '

Goals should be challenging and difficult, yet attainable. Goals that are too easy do not present a challenge, and therefore, can lead to less than maximal effort. Goals that are too difficult may sometimes lead to failure, which results in frustration. This frustration leads to lower morale and motivation. In between these two extremes are challenging and realistic goals.

TABLE 36.1

GOAL-SETTING PRINCIPLES

1. Set specific goals

2. Set realistic but challenging goals

3. Set long- and short-term goals

4. Set performance goals

5. Write down goals

6. Develop goal-achievement strategies

7. Provide goal support

8. Evaluate goal achievement

3.

& ' ( (

Many times injured athletes discuss a long-term goal o f returning to play after a serious injury. This goal is necessary and provides the fi nal destination for the athletes. It is important, however, for physicians to help them focus on short-term goals as a way in which to attain long-term goals. For example, a physician can make certain that an injured athlete sets daily and weekly goals in the rehabilitation process.

One way to employ this principle is to picture a staircase with the end or long-term goal at the top of the staircase, the present level of performance at the base o f the stairs, and the short-term goals as the steps in between.

4.

&%

It is important for sports medicine physicians to assist athletes in setting goals related to performance rather than outcomes (such as returning to play). Murphy (15) discusses "action goals" versus "re sult goals" being extremely important and often missed by physicians. With action-focused goals, athletes con centrate their energies on the "actions" o f a task as opposed to the "outcome." Action goals give focus to the task on hand, are under the athlete's control, and produce confidence and concentration. Result-focused goals, however, are not productive and often lead to slower recovery. These types o f goals give focus to irrel evant factors, things outside the control o f the athlete, and tend to produce anxiety and tension. For example, if a collegiate tennis player is working back after a seri ous shoulder injury, physicians can help him or her by setting action goals, such as lifting a certain weight or obtaining a certain degree of flexibility that will lead to the outcome, full recovery.

5.

)

Sport psychologists have recom mended that goals be written down and placed where they can be easily seen on a daily basis. Athletes may choose to write them on index cards and place them

6. in their locker, locker room, or bedroom. Many times physicians and athletes spend much time with goal setting strategies only to see them end up discarded in some drawer. The manner in which goals are recorded is varied, but the important fact is that they remain visible and available to athletes on a daily basis. This type of goal-setting may be very effective in helping athletes identify recovery goals (e.g., degrees of flexion) early in their rehabilitation from athletic injury. For example, the physical therapist/athletic trainer could write down the athlete's rehabilitation goals for the week on a card and they could both review this card at the end of the week.

If rehabilitation was successful in the short-term (weekly goals), such success should enhance an athlete's confi dence and focus for recovery and eventual return to play.

This aspect o f goal setting is often neglected, because goals are set with out appropriate strategies to achieve them. An analogy to this faulty process is like taking a trip from San

Diego to Buffalo without having a map. It will take one much longer to reach the final destination without a map. For example, physicians may encounter an athlete

598 ACSM's Primary Care Sports M edicine • www.acsm.org

with frequent flu-like symptoms. This athlete needs to employ appropriate strategies that will assist him or her in reducing the frequency o f these symptoms, such as working on improving nutrition, sleep hygiene, stress management, and/or time management.

7.

$

Research in the sport psychology literature has demonstrated the vital importance that other significant people play in helping athletes achieve goals. In fact, it has been shown that exercise adher ence is strongly affected by spousal support (6). Sports medicine physicians need to enlist the support and help of parents, faculty, friends, and others to help athletes focus on the actions required to achieve success (i.e.,

8.

* returning to play).

Evaluating progress toward goals is one of the most important aspects of goal setting, yet it is frequently overlooked. Injured athletes may spend considerable time in setting goals and de vising programs, but it will be for naught if they do not regularly monitor their progress in achieving these goals. To draw an analogy from philosophy, just as an unexamined life in not worth living, unexamined goal-setting is not worth doing.

AROU SA L C O N T R O L

W hat is A rousal C on trol?

Have you ever watched the NCAA basketball finals and wondered how a player can make a free throw or last second shot with thousands of people screaming and millions of people watching on television? If you are like most, we wonder in amazement at how athletes are able to remain calm during such times of high pressure and anxiety. The fact is that these athletes are actually nervous. The skill they have developed is to utilize this anxiety as a way to perform their very best. Similarly, when athletes become injured, they typically experience much anxiety as well as physical pain and lose their place in the line-up, or are unable, to perform something that has been a major part of their life for several years. Sports medicine physicians can help the athletes learn to utilize the anxiety surrounding their injury as a way to help them recover quicker.

The theories of arousal regulation are many. Some o f the more common theories include (21) Inverted-U theory (7),

Zone o f Optimal Functioning (ZOF), the multidimensional theory of anxiety developed by Martins et al. (13), and catastrophe theory as proposed by Thom (1975) and mathematically applied by Hardy and Fazey (9).

ARO USAL REGULATION TECH N IQ U ES

B reathing

Perhaps the most simple and most important technique to regulating anxiety is breathing (10). It is common for athletes to take short, quick breaths when confronted with a stressful event or situation such as rehabilitating an injury. With such choppy breaths, the breathing system contracts and does not supply enough oxygen to the body, particularly the muscles. This action results in the muscles becoming tense and fatigued, both o f which will prevent optimal performance in recovery. Taking slow, deep breaths allows athletes to supply their bodies with an adequate amount o f oxygen that will assist them in better recovery.

M uscle R elaxation

One o f the most potentially damaging aspects of anxiety for athletes is muscle tension (11). If an athlete's muscles are tense, he or she will not be able to perform the kinesthetic tasks required by their sport or rehabilitation process in a free-flowing and smooth manner. Therefore, for athletes to perform their best, they must learn to relax their muscles. If their muscles are not relaxed, the athlete's movements will be rigid, short, and tight.

How do athletes learn to relax their muscles? Edmund

Jacobson's (1938) progressive relaxation technique laid the groundwork for most current relaxation procedures.

His technique and other similar ones allow athletes to become aware of different muscle groups, how they hold tension in these areas, and also how to release this tension.

Sports medicine physicians can be extremely helpful by teaching these athletes to perform this mental skill as a way of making their rehabilitation less painful and return to play more quickly.

ATTEN TIO N AL A N D FO CU S SKILLS ___

Knowing

+

to focus on, and

+

to focus on it is essential for optimal athletic performance. Highly talented athletes often fail to achieve their best performance not because of lack o f ability, but rather o f an inability to focus on the "cues" that are necessary for optimal play.

For example, a baseball pitcher may be able to throw an excellent 91 M.P.H. slider in his warm-up, but if he is unable to throw it in a game situation, he is not likely to have optimal performance.

Concentration skills can be enhanced through the use o f mental skills, such as imagery, cognitive strategies, and attentional control strategies.

im a gery

What is the mystery in imagery that has helped elite athletes compete so well? There is no mystery at all. Imagery is a human capacity many people do not know about and/or have chosen not to use. It is a skill that very few athletes have developed to its full potential or realized its possible applications.

Imagery is a process by which sensory experiences are stored in memory and internally recalled and performed in

Chapter 36: Sport Psychology 599 the absence of external stimuli (Murphy, 1994). Imagery is more than visualization, more than just the sense of vision.

To maximize its potential, imagery must be a multisensory event, involving as many o f the senses as possible, including the sense of sound, touch, and movement.

Imagery has many uses for athletes, including regulating arousal level (3) and rehabilitation from injury (19).

Imagery is useful for coping with pain and injury by speeding recovery as well as keeping athletic skills from deteriorating. It is difficult for athletes to go through an extended layoff, but instead o f feeling sorry for themselves, they can imagine performing practice skills and thereby facilitate recovery.

C ognitive Strategies

Self-talk is one o f several different cognitive strategies in sport. It occurs whenever an individual thinks, either internally or externally. Sport psychologists are concerned with the self-talk o f athletes and how it influences their focus and concentration, arousal level, and performance.

The preponderance o f research supports the hypothesis that positive self-talk creates better or "no worse" performance.

Self-talk has a direct impact upon our emotional experience. If athletes are engaging in negative self-talk, their affective experience may be one o f frustration, anger, or extreme anxiety. These emotional states will challenge breathing, increase muscle tension, and create a loss of concentration and focus, resulting in lower performance.

However, if an athlete's self-talk is positive and relevant, the resulting emotional experience will be one o f relaxation, calmness, and centeredness; as a result, the chances of good performance increase dramatically. Sports medicine physicians can assist athletes by teaching and discussing positive self-talk and the differences it can make to recovery.

Attentional C ontrol S trategies

C O N C EN T R A T IO N

Concentration is the ability to focus all of one's attention on the task at hand. For physicians and their athletes, concentration is being able to direct all attention to the recovery process. When athletes experience anxiety, however, maintaining attention on the task at hand becomes more difficult and concentration becomes narrow and internally directed toward worry, self-doubt, and other task-irrelevant thoughts (16).

Part of the definition o f concentration involves paying attention to "relevant environmental cues". This ability to give one's full attention to only the relevant parts of a task is sometimes very difficult to do. Think about a football player recovering from a serious knee injury. What cues are relevant and what are irrelevant? Relevant cues include the rehabilitation process—keeping meetings with the physical therapist, good goal-setting, and following the physician's recommendations regarding treatment. Irrelevant cues, however, might include the thoughts o f friends or the next opponent on the schedule. These cues have absolutely nothing to do with rehabilitation. The physical actions required to rehabilitate the knee do not change regardless o f the next opponent.

Improving Concentration Skills

Physicians can be extremely beneficial in helping athletes maintain the concentration levels on the task at hand (i.e., rehabilitating an injury). First, sport physicians can remind the athletes that just as they are skilled to maintain focus in high-pressure situations (i.e., shooting free-throws to win a game), they can do this same thing in the recovery process.

Second, athletes can use cue words to help bring their full attention to the tasks in rehabilitation. For example, a tennis player recovering from an elbow injury might use the term as he or she lifts weights to strengthen the elbow or the word "breathe" to remind him or her that deep breathing will help relaxation during times of intense pain.

Research has demonstrated that routines can focus concentration and be extremely helpful in mental prepa ration (4,14,17). The mind can easily wander during rehabilitation. Injured athletes might worry about losing their position or the reactions of coaches and teammates.

These are the times in which routines are ideal. For example, when an athlete is performing rehabilitation exercises, he or she might take a deep breath, imagine what he or she wants to do in the session, and then say one or two cues words to maintain this focus.

The importance o f staying focused in the here and now cannot be overemphasized. Many times athletes get caught up in thinking about past injuries or what might happen to their position on the team after returning, causing them to lose focus on the relevant cues of the rehabilitation process at the present time.

In summary, to develop an effective mental skills plan, an athlete must incorporate the use o f many specific and defined behavioral skills in a structured manner. This type of detailed skill development requires more than a "he just needs mental toughness" approach. Rather, it is a systematic plan o f skills that are individualized to account for the athlete's age, skill level, sport-specific demands, and individual abilities.

PSY CH O LOG ICA L FACTORS

WITH ATHLETIC INJURY

An inevitable aspect of sports participation is the risk of athletic injury. Injuries ranging from lacerations to ligament sprains to fractured bones are an undeniable aspect o f the sports world. Yet, to frilly "treat" the injured athlete, what is done for his or her "psychological" (compared with

"physical") recovery? For example, to inform a patient that he or she is to have an anterior cruciate ligament

600 ACSM's Primary Care Sports Medicine • www.acsm.org

(ACL) reconstruction that will require surgery followed by extensive rehabilitation before his/her return to play is one aspect of care. What if the injury occurs 2 weeks before a championship contest? What happens on the day before a national scouting combine where his/her individual talents will be assessed with the potential reward being millions of dollars? At this point, a significant emotional, mental, and behavioral dynamic will occur, which should be treated.

A well-timed referral to a sport psychologist may enhance not only the emotional and mental recovery o f the athlete, but also physical recovery.

The purpose of this brief section is to review some of the expected emotional, behavioral, and cognitive re sponses o f the injured athletes. Ileil (1993) presented a comprehensive text that addresses many o f the psycholog ical dynamics of the injured athlete. For purposes o f this section, the following "stages" of response to athletic injuiy will be highlighted (Heil, 1993).

anxiety responses may be mild, moderate, or severe in regard to the disruption o f daily functioning for the athlete. A psychological referral for even mild anxiety may facilitate more effective coping and response skills given the therapeutic relationship.

An additional factor to consider is the athlete's decision making skills, as some athletes may not have a significant support system (e.g„ parents) available at the time of making a decision about treatment. If surgery is required, and the athlete has no previous surgical experience, there will be an adaptive anxiety to manage the realities of anesthesia, pain, and physical restrictions. If the athlete is a collegiate student-athlete and far from home (e.g., cross country or foreign), there will be additional stressors due to the distance from their primary support network. It is often at this stage that a referral to a sport psychologist may best assist the athlete in their recovery. The athlete may be more open to support during this time of decision-making, and a psychologist can assist in not only the decision-making process, but for emotional support.

Point o f Injury/lm m ediate Post-Injury

First, the most immediate emotional response at the point o f injury is shock; the degree of shock may range from minor to significant, depending upon the severity o f the injury. For example, an open fracture that is observed by the injured athlete may stimulate more o f a shock response than a minor laceration. However, individual personality differences may impact the shock response. Second, there may be a pattern o f emotional disorganization, where the individual may demonstrate atypical emotional responses to external or internal stimuli. For example, an injured athlete may become "giddy" on the sidelines during an examination. This response is an adaptive emotional response to a potentially traumatic event; it is a "normal" response to an abnormal event (injury trauma). Finally, the first denial response occurs, typically in an "I can't believe this happened" response. It is important to note that "denial" itself is an adaptive response that allows an individual to manage extreme emotional responses to situational stress.

As denial presents at the first stage o f injury, it may resemble an attempt to recover. This may become an unrealistic expectation of recovery. For example, the athlete with a diagnosed ACL tear may tell an athletic trainer

"I'll be reaidy to go next week"; in fact, the athlete may really believe this as truth during this stage. However, with little or no intervention, the reality of the injury will be confronted and the athlete will move to the second stage o f response.

T reatm en t D ecision and Im plem entation

This stage is filled with uncertainty for the athlete; lack o f knowledge o f medical treatments and potential rehabilitation may create excess anxiety. This "reactive" anxiety to the injury and treatment decision may become

"anticipatory" anxiety as surgery dates get closer. These

Early and Late R ehabilitative (Post-surgical)

Whether the intervention is surgical or non-surgical, there may be a series o f emotional, behavioral, and cognitive responses, which follow the implementation of treatment. Primarily, there may be affective responses that appear "atypical" to the athlete's baseline behaviors.

These emotional responses may be in the form of depression (acute), anger, confusion, and/or frustration.

Again, individual differences will vary on the basis o f the athlete's personality style, adaptive coping skills, and social

(e.g., family) support network.

If there are delays in scheduled recovery times, or dis ruptions in the healing process (e.g., infection), anger or withdrawal may become the affective response. Although anger is a difficult emotion to manage, a nonbehavioral dis play o f anger is an adaptive response. Because withdrawal is more "comfortable" for the health care provider, it may feel like an adaptation to injury; however, this withdrawal may exacerbate symptoms o f depression, which may lead to further disruption in functioning.

Another factor to consider in the psychological rehabil itation o f the injured athlete is social support networks. A team physician should be aware o f the athlete's team "envi ronment" during injury rehabilitation. If the environment is negative and punishing (athletes with some injuries are disregarded as "weak" or "faking"), the sports medicine per sonnel become more of a support network for the athlete.

Make sure to educate coaches and hold them responsible for the behaviors o f teammates attitudes/behaviors; how ever, it is primarily the coaching staff whose support is most needed (and often are most neglectful). The team physician and/or director o f sports medicine should have a supportive process for informing, educating, communi cating, and reinforcing an emotionally secure environment for the athlete to recover in.

Chapter 36: Sport Psychology 601

Return t o Play

This stage of injury rehabilitation often presents with the dynamics of fear and relief. These emotional responses may conflict with one another during what appears to be a desirable period for the athlete.. .returning to competition.

Fear of reinjury and fear of being able to compete and perform are typical affective responses for the athlete. When discussed and identified as "normal" adaptations to the emotional demands of competition and recovery, many athletes move through this stage well. When the athlete ruminates or obsesses about his or her full recovery status, the feelings of fear may create inhibition in rehabilitation, or perhaps even questions about their abilities. If the athlete has been working with a psychologist, these emotional and cognitive beliefs will have been discussed and processed, so adaptive plans would be ongoing and implemented. If the athlete has had no opportunities to discuss emotional responses to the injury, these fears may create significant disruption to coping (e.g., compliance to rehabilitation decreases).

The use o f mental imagery is often useful to facilitate the "relief' response and to visualize optimal performance in a healthy body. The use of imagery in injury healing, as well as return to play/action, can be an effective instrument in the psychological care o f the injured athlete.

These "stages" of the injury process will display a variety o f emotional (e.g., depression and anger), behavioral

(e.g., rehabilitation non-compliance), and cognitive (e.g., negative beliefs about future performance) responses from any athlete. Although these responses may range from mild to severe, a psychological referral can be helpful in facilitating an adaptive processing of these psychological demands. The sports medicine professional who aspires to a "holistic" care of the athlete should have, or create, the appropriate referral network for the psychological health o f the injured athlete. A psychologist can provide the supportive counseling/consultation to assist the athlete in his or her emotional and cognitive recovery from injury.

SP O R T P SY CH O L O G Y SERVICES

WITHIN A SPO R TS M EDICINE SETTING

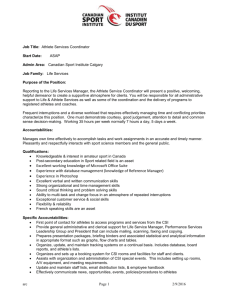

A sports psychologist is an important component to any sports medicine team. His or her practice is devoted to the psychological care and consultation with the athletic population regardless o f the level o f competition (i.e., professional, elite amateur, collegiate, high school, and other youth athletes). Services are also provided for other elite-performance organizations, including the performing arts and the military.

Psychological services provided include individual and group counseling (private practice), which may be third- party reimbursable for diagnostic conditions (e.g., injured athletes with m ood disorders). Often, the psychologist works in collaboration with primary care sports medicine physicians with medication management and counseling to provide the optimal level o f care for some mood and anxiety disorders. Other individual consultations may include performance-enhancement counseling, which uti lizes psychological skills to enhance athletic performance

(e.g., imagery skills for golf). Although many of these con sultations do not treat a specific Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual o f Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM - IV) di agnosis, the development o f cognitive and behavioral skills to enhance composure, confidence, and focus are desirable by many elite-level performers.

A staff psychologist may also provide consultation with sports organizations, and address both personal and per formance counseling issues. Additionally, educational and consultation work with coaching staffs, sports medicine staffs, and administrative staffs can enhance the devel opment o f optimal skills within the athletic environment.

This "positive" psychology orientation also leads to lectures and workshops in the surrounding community, including work in educational systems, medical systems, and youth sport organizations. The role of a licensed psychologist with sport psychology training/experience is an invaluable adjunct to a comprehensive sports medicine staff. The need and demand for services continue to develop as athletes and other elite performers seek to gain the "mental edge" in their competitive venues.

SUM M ARY

This chapter has briefly highlighted the area o f sport psychology as it relates to performance psycholog)' skills

(mental training); these skills may be o f interest to the practicing sports medicine professional. The issues related to the psychological rehabilitation of the injured athlete are o f obvious importance to sports medicine staff; the overview of affective responses will assist in understanding the normal and adaptive responses o f the injured athlete.

Finally, a brief description o f a psychologist's role within a sports medicine practice is presented.

The psychological issues that are present in the world o f sport and elite performance are numerous, and not all are mentioned in this chapter. Issues of eating disorders, substance abuse, and psychological health with athletes should be explored by the sports medicine professional.

This chapter may provide a brief introduction to the growing field of applied psychology within sports medicine.

R EFER EN C ES

1. Botlerill C. Goal setting for athletes with examples from hockey. In:

Martin CL, Hrycaik D, eds. Behavior modification and coaching: principles, procedures, and research.

Springfield: Charles C Thomas Publisher, 1983.

2. Carr C, Kays T. Survey o f Ohio State Athletics; 1997.

3. Caudill D, Weinberg R, Jackson A. Psyching-up and track athletes. A preliminary investigation. / Sport Psychol 1983;5:231-235.

4. Cohn PJ, Rotella RJ, Lloyd JW. Effects o f a cognitive behavioral intervention on the preshot routine and performance in golf. Sport Psychol 1990;4:33-47.

5. Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow. 1990.

6. Dishman RK, ed. Exercise adherence: its impact on public health.

Champaign:

Human Kinetics, 1988.

602 ACSM's Primary Care Sports M edicine • www.acsm.org

7. Hanin YL. A study o f anxiety in sport. In: Straub WF, ed. Sport psychology: an analysis of athlete behavior.

Ithaca: Mouvement, 1980.

8. Hardy CV, Richman JM, Rosenfeld LB. The role of social support in the life stress/injury relationship. Sport Psychol 1993;5:128-139.

9. Hardy, L, Fazey J. The inverted U-hypothesis: a catastrophe for sport psychology. Paper presented at the annual meetings of the North American society for the psychology of sport and physical activity.

Vancouver, British

Columbia, Canada, 1987.

10. Harris, DV. Relaxation and energizing techniques for regulation o f arousal.

In: Williams JM, ed. Applied sport psychology: personal growth to peak performance.

Palo Alto: Mayfield, 1986.

11. Landers DM, Boutcher SH. Arousal-performance relationships. In: Williams

JM, ed. Applied sport psychology: personal growth to peak performance.

Palo Alto:

Mayfield, 1986.

12. Locke EA, Latham GP. A theory of goal setting and task performance.

Englewood

Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1990.

13. Martins R, Vealy RS, Burton D. Competitive anxiety in sport.

Champaign:

Human Kinetics, 1990.

14. Moore WE. Covert-oven service routines. The effects o f a service routine training program on elite tennis players. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation.

University of Virginia, 1986.

15. Murphy S. The achievement zone.

New York: GP Putnam's Sons, 1996.

16. NidefFer, RM. Concentration and attentional control training. In:

Williams JM, ed. Applied sport psychology: personal growth to peak performance.

Palo Alto: Mayfield, 1993.

17. OrlickT. Psyching for sport: mental training for athletes.

Champaign: Leisure

Press, 1986.

18. Van Raalte J, Brewer B. Exploring sport and exercise psychology.

Washington:

American Psychological Association, 1996.

19. Weinberg RS, Gould D. Foundations of sport and exercise psychology.

Champaign: Human Kinetics, 1995.

20. Weinberg RS, Weigand D. Goal setting in sport and exercise: a reaction to locke. / Sport Exerc Psychol 15:88-95.

21. Yerkes RM, Dodson JD. The relation o f strength and stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. J Comp Neurol Psychol 1908;18:459-482.