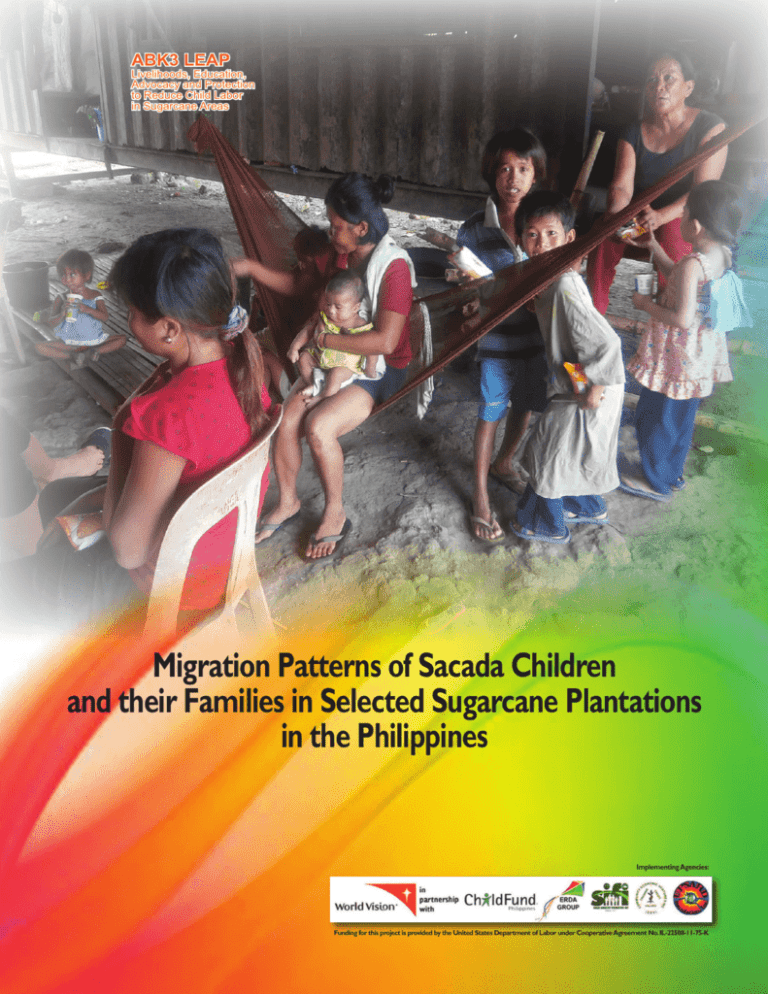

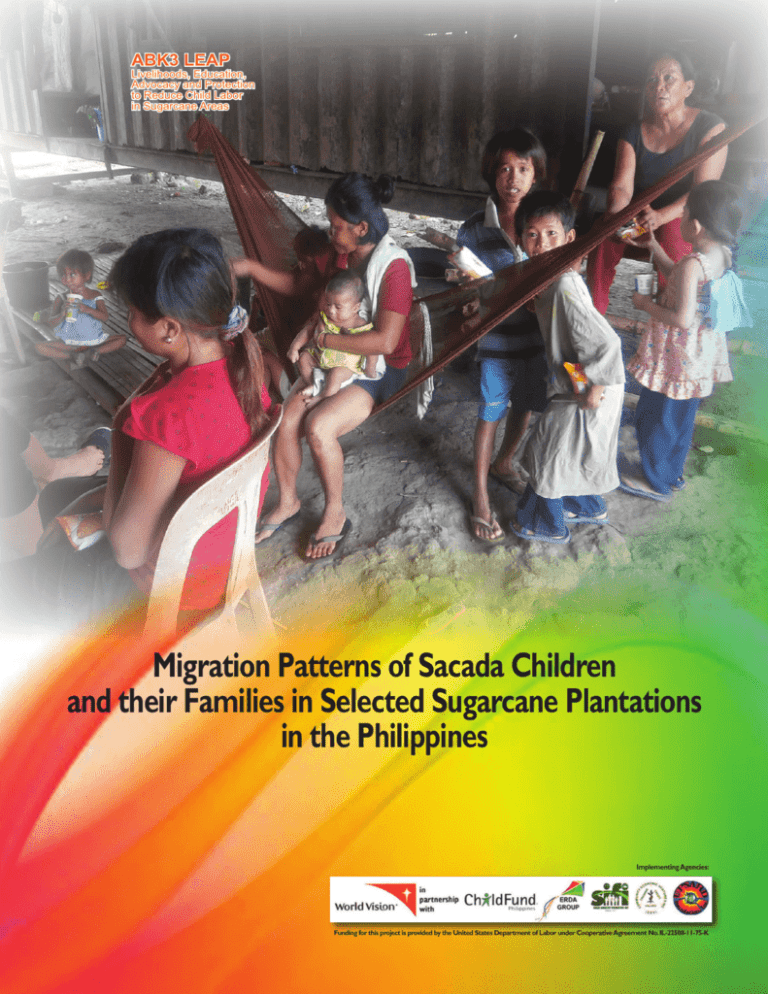

ABK3 LEAP

Livelihoods, Education,

Advocacy and Protection

to Reduce Child Labor

in Sugarcane Areas

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children

and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations

in the Philippines

Implementing Agencies:

Funding for this project is provided by the United States Department of Labor under Cooperative Agreement No. IL-22508-11-75-K

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children

and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations

in the Philippines

University of the Philippines Social Action and Research for Development Foundation, Inc.

(UPSARDFI)

July 2015

This document does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Department of Labor,

nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement

by the United States Government.

ABK3 LEAP RESEARCH PROGRAM STAFF

Jocelyn T. Caragay

Program Director

Ma.Theresa V.Tungpalan, PhD

Program Associate

Josefina M. Rolle

Research Associate

Maricel P. San Juan

Administrative Assistant

SACADA PROJECT STAFF

Editha Venus-Maslang, DPA

Project Director

Beatriz P. del Rosario, PhD

Research Associate

Josephine Gabriel-Banaag

Jona Marie P. Ang

Research Assistants

Janette B.Venus

Data Analyst

Emmanuel N. Ilagan

Editor

Acknowledgements

The Research Team of the University of the Philippines Social Action and Research for Development

Foundation (UPSARDF), Inc. wishes to acknowledge the support and cooperation of the following in the

completion of this study “Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane

Plantations in the Philippines”:

The Governor of Aklan, Mayors and Barangay Captains of the sending (Aklan) and the receiving provinces

(Batangas, Negros Oriental, Negros Occidental) for giving their time, support and cooperation during data

collection and field validation;

Representatives from the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), Department of Labor

and Employment (DOLE), and Department of Agriculture (DA)-Sugar Regulatory Administration (SRA) for

serving as key informants and for assisting the Research Team in coordinating the field visits;

The Sugar Mill district officers, Cooperative officers, contractors, planters, foremen (cabos), and the young

and adult migrant sugarcane workers (sacadas) and their families for participating in the survey, focus group

discussion, case studies, and key informant interviews;

The Provincial Engagement Officers of World Vision Development Foundation, Inc. (WVDF); ChildFund (CF),

Educational Research Development Assistance Group (ERDA), and the Sugar Industry Foundation, Inc (SIFI)

of the four (4) covered provinces for providing the needed assistance in coordinating with the Local

Government Units (LGUs) and other key partners in their respective areas;

The ABK3 Project Management Team and Technical Working Group for their endless support in all phases

of the research; and

The faculty, staff, students and friends of the College of Social Work and Community Development of the

University of the Philippines – Diliman for their participation during the initial presentations of the research

findings.

Contents

List of Tables

List of Figures

Abbreviations

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

12

Chapter 1

Introduction17

Study Objectives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Analytical Framework. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Chapter 2 Findings

19

19

25

Who are the Sacadas? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Hacienda System and Roots of Sacada Work

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Sugar Industry

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Child Laborers in Sugarcane Plantations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Responding to Sacada Needs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Sacadas in Receiving Provinces: Batangas, Negros Oriental

and Negros Occidental . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Sacadas in a Sending Province: Aklan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

25

26

27

32

33

51

Case Studies

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

42

Chapter 3

Analyses, Conclusions and Recommendations97

Psycho-social and economic conditions of sacada adults,

children and their families . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

97

Protective and risk factors involved in sugarcane work . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

Coping mechanisms and the effects of seasonal migration

on children

.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

Annexes

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

114

References

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

160

List of Tables

No.

Description

Page No.

1

Distribution of Respondents by Age Category and by Province

23

2

Sacadas’ Living Conditions in Home Province (HP) and Current Workplace (CW)

37

3

Sacadas’ Perceived Similarities and/or Differences between their Living Conditions in their

Home Province and Workplace

38

4

Sacadas’ Perceived Ability to Provide for Family Needs

39

5

Sacada Parents’ Perceptions and Values on their Relationship with Children and Working

Children: Receiving Provinces

40

6

Perceptions and Values of Sacada Respondents (with and without children) on Family and

Social Relationships and on Working Children: Receiving Provinces

41

7

Sacada Parents’ Perceptions and Values on their Relationship with Children and Working

Children: Aklan

45

8

Perceptions on Community Situation

47

9

Perceptions and Values of Sacada Respondents (with and without children) on Family and

Social Relationships and on Working Children: Aklan

47

10

Psycho-Emotional Condition of Children Left Behind

48

11

Social Support Available to Children Left Behind

49

List of Figures

No.

Description

Page No.

1

Interplay of Variables Influencing Child Labor and Migration

21

2

Organizations and Individuals Interacting with Sacada Children and their Families

22

3

Sacada Work Process

95

4

Sacada Income Distribution System

95

A B B R E V I AT I O N S

4Ps

Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program

ABK

Ang Pag-aaral ng Bata Para sa Kinabukasan

ALS

Alternative Learning System

BCPC

Barangay Council for the Protection of Children

BHW

Barangay Health Worker

BWSC

Bureau of Workers with Special Concerns

CADPI

Central Azucarera Don Pedro Inc.

CCT

Conditional Cash Transfer

CEVI

Community Economic Ventures, Inc.

CIRMS

Center for Investigative Research and Multimedia Services

CLMS

Child Labor Monitoring System

DA

Department of Agriculture

DAR

Department of Agrarian Reform

DepEd

Department of Education

DILG

Department of the Interior and Local Government

DOH

Department of Health

DOLE

Department of Labor and Employment

DSWD

Department of Social Welfare and Development

DTI

Department of Trade and Industry

ERDA

Educational Research and Development Assistance Foundation

FGD

Focus Group Discussion

HELP ME

Health, Education, Livelihood, Prevention, Protection, Prosecution, Monitoring, and Evaluation

IACAT

Inter-Agency Council against Trafficking

ILO

International Labour Organization

I-SERVE

SACADAS

Integrated Services for Migratory Sugar Workers

KALAHI-CIDSS Kapit-Bisig Laban sa Kahirapan-Comprehensive Integrated Delivery of Social Services

KII

Key Informant Interview

LCPC

Local Council for the Protection of Children

LEAP

Livelihoods, Education, Advocacy and Social Protection to Reduce Child Labor in Sugarcane

LGUs

Local Government Units

MDDCFI

Mill District Development Council Foundation Inc.

MPC

Multi Purpose Cooperative

MSW

Migratory Sugar Workers

NATTF

National Anti-Trafficking Task Force

NBI

National Bureau of Investigation

NCLC

National Child Labor Committee

NGO

Non-Government Organization

NSO

National Statistics Office

OFWs

Overseas Filipino Workers

PCA

Philippine Coconut Authority

PIA

Philippine Information Agency

POs

People’s Organizations

PPACL

Philippine Program Against Child Labor

PSWDO

Provincial Social Welfare and Development Office

RID

Regional Intelligence Division

SBM

Sagip Batang Manggagawa

SIFI

Sugar Industry Foundation, Inc.

SRA

Sugar Regulatory Administration

SSS

Social Security System

TESDA

Technical Education and Skills Development Authority

TWG

Technical Working Group

UP CSWCD

University of the Philippines College of Social Work and Community Development

UPSARDF

University of the Philippines Social Action and Research for Development Foundation

USDOL

United States Department of Labor

WHO

World Health Organization

WVDF

World Vision Development Foundation

Sacadas hauling sugarcanes on to a truck in Nasugbu, Batangas

Executive Summary

The University of the Philippines Social Action Research and Development Foundation (UPSARDF), Inc.

conducted a Study on “Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane

Plantations in the Philippines” under the World Vision ABK3 LEAP program, during the period February

2014 to July 2015. The Study aimed to draw some policy and program implications that will address the

plight of the sacadas.

The Study focused on the following:

1.

2.

3.

Psycho-social and economic conditions of sacada adults, children and their families

Protective and risk factors involved in sugarcane work

Coping mechanisms and the effects of seasonal migration on children

Data collection was done in four (4) provinces, namely Batangas, Negros Oriental and Negros Occidental

(“receiving” provinces where sacadas work), and Aklan (“sending” province where sacadas originally lived).

Two (2) barangays per municipality, and one (1) municipality per province were considered in this Study.

The main criteria used in selecting the provinces were: a) sugarcane is the main crop, and b) many workers

temporarily migrating to work in a sugarcane plantation in another location.

The methods used in the Study included case studies, survey interviews, key informant interviews and focus

group discussions. A total of 247 survey respondents from the four (4) provinces were covered consisting of

adults (199 or 81%) and children (48 or 19%). A big majority of the children interviewed came from Aklan.

Data collection for children working as sacada was limited by the difficulty of locating them in the receiving

provinces. This may be attributed to the growing awareness of the sacadas and their contractors of the

laws and policies governing child labor and the on-going vigorous inter-agency campaign on “child labor-free

barangays” led by the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE). Moreover, the attendant consequence

of violating child labor laws (e.g., the imprisonment of a recruiter or contractor) has inhibited the contractors

and adult sacadas in disclosing any information on the presence of child workers in the sugarcane fields.

The findings showed that sacada work is linked to the country’s socio-economic conditions that perpetuate

poverty. For as long as poverty exists, no amount of regulations would suffice to prevent families from allowing

their children to work. Unless the poverty cycle ends, the negative aspects of sacada work will always remain.

The uneven economic development has made some municipalities prosper while others impoverished. The

communities where the sacadas live are among the poorest, most marginalized and neglected. The sacadas

Page 12

Executive Summary

are caught in the “poverty trap” characterized by the web of material poverty, vulnerability, powerlessness,

physical weakness and isolation as cited by Chambers (1983). Thus, specific interventions should be developed

that will address each of these poverty elements.

Sacada work is passed on from one generation to another and is therefore inter-generational. Some adults

interviewed started sacada work at a young age – 12 to 16 years old and continue as sacadas into adulthood.

In cases where a sacada parent could no longer continue or voluntarily retire for health or some other

reason, the son takes over. The son works as sacada until the cash advance / loan from the labor contractor

is fully paid. Even after the loan is paid the meager take-home pay however prevents him from sending his

children to school and giving them a better future.

Both the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) and the DOLE have reported a significant

reduction in the number of child laborers in sugarcane plantations.They attributed this to the strict monitoring

of child labor and human trafficking cases via an inter-agency approach.

However, the study showed that child labor in sugarcane

plantations continues to exist despite the government’s efforts

to mitigate it. Their parents have allowed them to work at an

early age for them to contribute to the family coffers. However,

child labor cases are not discussed in the open due to the

existence of child labor laws and policies.Thus, children working

as sacada have remained hidden, undocumented and unprotected.

Although child labor is not allowed, some sugar mill industry

focal points and barangay officials showed tolerance towards it.

The Tripartite Mill District Committee in Batangas, formulated a

voluntary code of conduct allowing children to work (although

only light work) in sugarcane plantations.

Children working as

sacada have

remained hidden,

undocumented and

unprotected.

There are existing policies and programs that address sugarcane workers in general; however, their

enforcement would need to be monitored and as needed, strengthened and enhanced. These include the

following: the Social Amelioration Act; DSWD’s 4 Ps (Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program); non-government

organization (NGO)’s support; DOLE’s monitoring that seeks to ensure provision of living necessities (good

housing conditions, water and toilets) to the sacadas; DOLE’s child labor-free barangay campaign; and DOLE’s

Integrated Services for Migratory Sugar Workers (I-SERVE Sacadas).

While policy and program interventions exist, key informants from the municipal local government units

(LGUs) claimed no knowledge about the I-SERVE program and understandably have not accessed any benefit

from it. Moreover, while the government through DOLE has developed and implemented a social amelioration

program for the sacadas, it has yet to reach the sacadas covered by the present Study. Hence they do not

enjoy social and legal protection.There is a need therefore to intensify awareness promotion not only among

the LGUs but more importantly, among the sacadas for them to gain access to services and benefits.

Because their principal concern is earning enough money for their families to survive, sacadas have very

limited involvement in community activities outside their families. Their sense of collectivity and confidence

in their own power to alter their lives for the better is very low. Needless to say having a shared vision and

common interest for their families and community is almost nil.

Page 13

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations in the Philippines

Sacadas have remained isolated in their workplace and their mobility and interaction with other people in

the surrounding community are restricted. To prevent the sacadas from encountering problems with the

community people, the foreman/cabo always sees to it that they are confined within the barracks. They are

prevented from mixing with the locals. They leave early for work and come back late afternoon or evening.

They do not participate much in recreational activities (except for some who allegedly drink or gamble).

Even their families left in the barracks have nothing productive to do while waiting for their sacada spouse

to return from work.

Families of sacadas left behind in their home provinces are faced with psycho-social challenges that need

to be addressed. Social relationship among children is generally confined to immediate family members. The

presence of some support system, e.g., grandparents or other relatives alleviates the burden of temporary

separation of the sacadas from their families. Spouses left behind engage in other means of livelihood, that

provide them temporary relief from loneliness and at the same time augment their family income. Academic

institutions that have community outreach programs may be tapped to place community organizers in the

communities to facilitate activities that can help uplift the self-image and self-worth as well as social skills of

the sacadas and their families.

Sacadas have moved from one province to another – from their home province in the Visayas to different

parts of Luzon (Negros/Antique-Pampanga-Batangas-Isabela). The migration pattern of sacadas remains to

be seasonal and transitory. The seasonal migration movement is now towards Isabela as it offers higher pay

due to its eco-fuel industry.

The term “sacada” has several local connotations. What makes it unique is that it involves some form of

temporary, seasonal migration and is particular to a specific nature of work – harvesting and cane hauling.

The other term associated with sugarcane work is the “dumaan”. Dumaans are permanent farm workers

who work in the haciendas whole-year round, albeit for two (2) to three (3) days a week only.

In a sense, there is no clear-cut delineation between a sacada and a dumaan. They can be sacada at one point

and dumaan at another point once they go back to their hometown to work in a sugarcane plantation.This is

especially true for those living in the Negros provinces. They do sacada work in a nearby municipality and go

back at the end of the day to their homes. Given that one can be a sacada and a dumaan at different points,

the concept of “sacada” may need to be redefined to reflect this peculiarity.

The strenuous, back-breaking, and heavy lifting tasks under the heat of the sun involved in harvesting and

hauling cane definitely present not just health and physical but also emotional hazards to a child sacada.There

is no question that children must not be allowed to work as sacada.

Recommendations

Policy implications

1.

2.

Page 14

Raise awareness among the country’s legislators and policy makers on the sacadas’ plight, i.e., as the

most deprived group in the agricultural worker sector who have been trapped in the poverty cycle

from generation to generation.

Amend and strengthen the Social Amelioration Act to include specific welfare and protection

provisions for sacadas and their families.

Executive Summary

3.

4.

5.

Expand the mandate of the Tripartite Committee to include monitoring and reporting of compliance

to labor standards on hours of work, working conditions, employee benefits, etc., by planters and

sacada labor contractors, particularly in ensuring the safety, protection and welfare of the sacadas.

Create special laws to address the needs of sacadas, given the transitory and migratory nature of

their work; for instance, providing them with an employment identification card that they can use to

avail themselves of work benefits regardless of their work location.

Engage academic institutions that have community outreach programs to inform sacadas of their

rights and benefits as agricultural laborers; use mass media as necessary.

Program implications

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

Strengthen intra-barangay and inter-barangay level monitoring on possible violations of child labor

laws; form a multi-sectoral structure within barangays to monitor and report as well as expeditiously

act on child labor cases.

Actively explore alternative means of livelihood that utilize existing local assets and resources coupled

with infrastructure and marketing support; provide skills enhancement and alternative livelihood and

skills training to spouses left behind.

Encourage the organization of sacadas for them to be represented in a tripartite sugar committee,

where they can be given voice to present their concerns and needs. Organize sacada cells (with 5 to

10 families in each cell) to identify, plan and carry out activities that will promote their interest and

well-being; organize a separate cell for sacada children for the same purpose.

Strengthen positive cultural values (providing for family needs, honoring financial obligations, sense

of responsibility) but at the same time ensure that the rights and welfare of children are protected

and upheld.

Vigorously promote responsible parenthood and child well-being; strengthen family interventions

(family development session, counseling, etc.).

Conduct more awareness activities to promote child rights, including advocacy on child rights among

those involved in hiring sacadas, such as contractors, plantation owners, sugar mill industry focal

points.

Strictly enforce policies and programs that address the needs and concerns of the sacadas.

Publicly recognize through government awards or incentives those planters, millers and contractors

who fully comply with labor laws and standards.

Redefine the concept of “sacada” to reflect the mix of “sacada” and “dumaan” work features.

Page 15

Interview with a family of sacadas in Mabinay, Negros Oriental

Chapter One

Introduction

Several international and national legal instruments have been enacted to eliminate the worst forms of child

labor. For instance, in the 2010 Global Child Conference towards a World Without Child Labor held in the

Hague, Netherlands, the multi-sector participants agreed on measures to accelerate progress towards the

elimination of the worst forms of child labor by 2016 while affirming the International Labor Organization

(ILO) Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (1998) and ILO Conventions of 1973

and 1999.

At the national level, the Philippine Program against Child Labor (PPACL) Strategic Framework 20072015 lays out the blueprint for reducing the incidence of child labor by 75 percent by 2015. Apart from

child labor, the Philippines also has taken actions specifically to address the issue of trafficking with the

creation of the Inter-Agency Council against Trafficking (IACAT) and the National Anti-Trafficking Task Force

(NATTF) to promote collaboration between the police and prosecutors as well as service providers in

developing a stronger case against traffickers (Department of Labor Bureau of International Labor Affairs,

July 2011).

In December 2013, the 12th Congress of the Philippines enacted Republic Act No. 9231, “an Act providing

for the elimination of the worst forms of child labor and affording stronger protection for the working child,

amending Republic Act No. 7610, which is the ‘special protection of children against child abuse, exploitation

and discrimination Act’. The Act provides special protection to children from all forms of abuse, neglect,

cruelty, exploitation and discrimination, and other conditions prejudicial to their development including child

labor and its worst forms, among others.

According to the Philippines 2007 Labor Force Survey, approximately 2.3 million children aged 5-17 years or

eight (8) percent of the total age group worked in the Philippines. Roughly, 56 percent of working children

worked in agriculture, hunting and forestry. In agriculture, children worked in the production of bananas,

coconuts, corn, rice, rubber, sugarcane, tobacco, and other fruits and vegetables. Children working in the

sugarcane sector are involved in planting, weeding, cane cutting, farm clearing, harvesting, hauling, pesticide

and fertilizer application, burning, preparation of cane tops and the counting and distribution of seedlings.

(Department of Labor, 14 July 2011). Poverty has been a major contributory factor to child labor in the

Philippines, which is supported by several studies on child labor and migration.

A study conducted by the Save the Children UK Philippines on the impact of migration on children in Cebu

City (October 2002) showed several converging factors that trigger migration: food shortage brought about

by a drop in agricultural production; unemployment; weak domestic markets; unstable family income; limited

educational facilities for children; and inflationary pressures (high transport costs, bad roads, etc.).

Specifically on children working in sugarcane plantations,World Vision, in collaboration with some government

and sugar industry stakeholders undertook a rapid assessment of all sugarcane provinces with the end-view

Page 17

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations in the Philippines

of designing a project to target geographic areas and beneficiaries where it can make the greatest impact

given its available resources.

The ABK3 LEAP (Livelihoods, Education, Advocacy and Protection) against Exploitative Child Labor in

Sugarcane document (31 August 2011) reveals that there are 17 provinces that grow sugarcane in the

country – two (2) of which are in Negros that produce more than 58 percent of the total production. The

research was able to rank and choose the 11 targeted provinces based on certain criteria, i.e., sugarcane

production, number of farms, 2009 annual per capital poverty threshold, poverty incidence, magnitude of

poor families, net enrollment, elementary school survival (drop-out) rate, elementary classroom-pupil ratio,

and rural population.

In addition, it considered the provinces where ABK3 LEAP partners have already collaborated, and took

into account the limited resources and economies of scale. Based on the assessment results, ABK3 LEAP

project implementers1 designed a project that aims to reduce child labor in sugarcane areas through the

following: provision of direct services and linkages; institutional capacity strengthening through improved

policies, programs and service delivery; awareness-raising on exploitative child labor in sugarcane and on

the importance of education; research, evaluation, and collection of data to address gaps in knowledge,

improve monitoring, and increase the effectiveness of direct interventions to combat exploitative child labor

in sugarcane; and the ensuring of sustainable efforts to reduce exploitative child labor.

As part of research and knowledge generation, the University of the Philippines College of Social Work

and Community Development (UP CSWCD) through the UP Social Action and Research for Development

Foundation (UPSARDF), Inc. did an in-depth baseline study of the ABK3 LEAP areas. The study reaffirmed

that poverty coupled with the strong desire to help meet their family’s survival needs had prompted children

to work in sugarcane plantations. Among the issues confronting child laborers were: the health risks involved

in their sugarcane work; the lack of financial capacity to pursue and complete their education; the lack of

awareness of government education support policies and programs; and the additional demand to perform

domestic chores on top of their work.

Hans van de Glind (2010) prepared a working paper on migration and child labor with focus on child migrant

vulnerabilities and on children left-behind. He concluded that despite the growing body of evidence with

regard to the effects of migration on children, there remain significant knowledge gaps, and further analysis

needs to be done on the correlation between migration and child labor.

The previous studies done on child laborers in sugarcane plantations are good and important references for

determining further areas of research that can broaden and deepen one’s knowledge and understanding of

their situation; particularly the core problems and issues, the possible risks, and the coping and protective

mechanisms both inherent and available to child laborers and their families. It is envisaged that the findings of

the study will help policy-makers and program implementers in redesigning appropriate program interventions

towards enhancing the well-being and protection of children working in exploitative forms of labor within

and outside their place of origin.

WVDF, Child Fund International (CF), Educational Research and Development Assistance (ERDA), Sugar Industry Foundation,

Inc. (SIFI), and Community Economic Ventures, Inc. (CEVI)

1

Page 18

Introduction

Study Objectives

General Objective: The study broadly aims to describe and analyze the situation and effects of labor and

migration on child workers and their families in sugarcane plantations.

Specific Objectives:

1.

To describe the psycho-social, educational and economic conditions of child workers who are either

left behind, living independently or living with their parents, such as, but not limited to the following:

a.

Motivations, aspirations, feelings and perceptions

b.

Socialization and social relationships of child laborers and of children left behind by parents

c.

Community involvement

d.

Income and access to resources

e.Education

f.

Health condition

2.

3.

4.

5.

To determine the protective and risk factors involved in sugarcane work, including the working

conditions at the sending area2 and receiving area of sacada children and their families;

To identify the effects of migration on children;

To determine how children and their families cope with work-related problems, issues and concerns;

and

To track the movement of sugarcane child laborers and their families and recommend ways on how

to address their problems.

Analytical Framework

Hans van de Glind (2010) notes that migration can be an important determinant for child labor. His paper

focuses on voluntary migration, excludes child trafficking and distinguishes three categories as follows: 1)

children who migrate with their parents; 2) independent child migrants; and 3) children left-behind by migrant

parents. As his paper analyzes the global context of child labor and migration, the study adopts the same

categories in the local context, and also looks into the implications of child trafficking particularly among

independent child migrants.

For all three types of child labor and migration, the same variables will be examined as follows: 1) psychosocial; 2) economic; 3) protective and risk factors; and 4) coping mechanisms. Each is described briefly as

follows:

Psycho-social factors

Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development is one of the best-known theories of personality in

psychology. Erikson’s theory describes the impact of social experience across the whole lifespan.

Situation in the sending area will be based mainly on the description to be provided by the study respondents as they narrate

their family history and the major past events and conditions in their lives.

2

Page 19

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations in the Philippines

One of the main elements of Erikson’s psycho-social stage theory is the development of ego identity.

Ego identity is the conscious sense of self that we develop through social interaction. According to Erikson,

our ego identity is constantly changing due to new experiences and information we acquire in our daily

interactions with others. When psychologists talk about identity, they are referring to all of the beliefs, ideals,

and values that help shape and guide a person’s behavior. The formation of identity is something that begins

in childhood and becomes particularly important during adolescence, but it is a process that continues

throughout life. Our personal identity gives each of us an integrated and cohesive sense of self that endures

and continues to grow as we age (Kendra, n.d.).

The study looked into the psychosocial make-up of the child laborers – their motivations, aspirations,

perceptions, beliefs, ideals and values. Unlike previous studies done, the study dug deeper into how child

laborers’ values and beliefs are shaped by their social environment.

Economic factors

Using the concept of decent work in labor migration and rural workers, the study examined the general

economic condition of child laborers and their families, particularly on the social cost involved in either

leaving the family behind or bringing in the family into the internal migration process.

Protective and risk factors

What are risk and protective factors? They are the aspects of a person (or group) and environment or

personal experience that make it more likely (risk factors) or less likely (protective factors) that people will

experience a given problem or achieve a desired outcome. Risk and protective factors are keys to figuring

out how to address community health and development issues. It is a matter of taking a step back from

the problem, looking at the behaviors and conditions that originally caused it, and then figuring out how to

change those conditions (Community Tool Box, n.d.).

The study explored the different risks that beset sugarcane child laborers and their families. It sought to

determine the types and effects of social protection accorded to sugarcane child laborers and their families

by the different organizations operating in the areas. The already established mechanisms against human

trafficking and child labor were re-examined on the extent that they are able to protect child laborers from

abuse.

Coping mechanisms

Coping has been defined as the ‘person’s constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to meet

specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the

person’ (Lazarus, 1998, p. 201). Generally, a distinction is made between two ways of coping. Problemfocused coping is ‘vigilant coping’, aimed at problem solving, or doing something to alter the source of the

stress to prevent or control it. Emotion-focused coping is aimed at reducing or managing the emotional

distress associated with the situation (Carver et al., 1989; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). The former tends to

predominate when something constructive can be done. It has been described as active coping; the latter

tends to predominate when the stress is something that must be endured.

The separation of the families from the child laborer or the seasonal migration of the whole family may cause

changes in the family structure. The study looked into how family members especially the children are able

Page 20

Introduction

to survive their situation, and how children and parents manage and solve their problems. It also delved into

the existing and needed support system to help them cope with their challenging situation.

The following diagram shows the interplay of factors or variables that could influence child labor and

migration:

Figure 1: Interplay of Variables Influencing Child Labor and Migration

Migration patterns may be explained by the degree of awareness or perception of child laborers and their

families on the working conditions and opportunities at either the sending area or receiving area. Personal

and familial factors (values, beliefs, social interaction) and environmental factors (availability of resources and

opportunities plus support policies, programs and services) may also serve as determinants of migration.

Page 21

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations in the Philippines

Figure 2: Organizations and Individuals Interacting with Sacada Children and their Families

The above figure shows the key individuals and organizations that interact with the sacada children and their

families. Each could play a role in the life of a sacada child and his/her family, which could affect or influence

his or her well-being.

Research Design and Methods

The study is a combination of exploratory and descriptive research designs. It employs a mix of quantitative

and qualitative methods. There are two major components: the first one sought to establish the migration

patterns of sugarcane child laborers and their families through survey and review of relevant documents;

the second aimed to gain a deeper understanding of the psycho-social factors, including how they cope, the

risks involved in their work, and the social protection measures available to help reduce the burden of child

laborers. The latter was done through case studies of children and their families. Focus group discussions

were also done with selected groups, including child laborers and their families.

Each method is described briefly in the following:

Survey interviews

The study was conducted in four of 11 (or 36%) covered provinces of ABK3 LEAP project – Batangas

in Luzon; and Negros Occidental, Negros Oriental and Aklan in the Visayas. The first three provinces are

classified as ‘receiving’ provinces (where the sacadas go to for work), while Aklan as the ‘sending’ province

(the home province or place of origin of the sacadas).

Page 22

Introduction

The following shows the distribution of respondents by province:

Table 1: Distribution of Respondents by Age Category and by Province

Number (No.) of Adult

Respondents

No. of Child

Respondents

Total

Aklan

31

30

61

Batangas

53

6

59

Negros Occidental

52

7

59

Negros Oriental

63

5

68

Total

199

48

247

Province

The number of children per receiving province was very few; thus, they were considered as part of the case

studies instead.

Selection of municipalities/barangays per province was done in consultation with the local government

agencies (DSWD/DOLE). Municipalities were chosen based on their known number of sacadas.

Focus group discussions (FGDs)

For each province, FGDs were undertaken separately with some sacada parents, children of sacadas, and

some local agency representatives.

Key informant interviews

Key informant interviews were also conducted with the focal persons from the Department of Labor and

Employment (DOLE), the manager of Integrated Services for Migratory Sugar Workers (ISERVE) Sacada

program, some farm managers and/or the sacada contractors/middlemen. Interview questions revolved

around the work conditions and arrangements of sacadas.

Page 23

Temporary shelter for sacadas in Barangay Cogonan, Nasugbu, Batangas

Chapter Two

Findings

Who are the Sacadas?

There are two categories of sugarcane plantation workers: Sacada and Dumaan.

Sacada (or sakada) is the Filipino/Tagalog word for a seasonal cane cutter (Asia Watch Report, 1990, p. 113)

and seasonal daily wage laborer (Corpuz, 1992) working in a sugarcane plantation. Sacadas are usually hired

as temporary migrant workers during the peak harvest and milling season, from October/November to April

or May.

Sacadas are the hacienda’s living proof that colonial-period migrant labor in the Philippines persists in the

“new millennium”. The ordinary sacada is the oppressed worker, migrant, and peasant twice over. Receiving

abysmally-low wages and denied benefits, many of the sacadas hail from the Visayas, where many haciendas

are found (Ito & Olea, 2004).

Dumaan (or duma-an) are permanent farm workers who work in the haciendas whole-year round, albeit

for two to three days a week only. During the Spanish colonial times, dumaans were effectively permanent

subsistence laborers. Often they fell into a form of debt peonage through unpaid credit at estate-stores that

rendered their salaries largely insufficient.

Although the plight of dumaans who reside in a hacienda is difficult, the situation of sacadas is a lot worse

(Billig, 2003, p. 39).

Based on key informant interviews with the DOLE representatives in Batangas and Negros Occidental, the

term “sacada” is likened to slavery dating back to the Spanish period. Hence, DOLE had replaced it with the

phrase “migratory sugar workers” (MSW) to refer to those who, in order to cut canes during the milling

season, have transferred from one province to another, or from one town to another within the same

province. Essentially, migratory sugar workers are people who transfer work locations.

The original concept of “sacada” is a tabasero or laborer from Panay Island hired by the planter through

transaction with a contractor for the purpose of cutting and loading sugarcanes in the Negros province.

As the years passed, the term “sacada” grew to encompass locals from Negros. For example, planters in

Binalbagan, Negros Occidental hire people from Mabinay, Negros Oriental. These workers typically have the

option to stay in the assigned barracks or return occasionally to their hometowns.

When sugar mills in Negros Oriental and South Occidental are either closing already or have stopped

altogether, people go to North Occidental to find work. Sacadas from provinces outside Negros normally

work in South Occidental; when the rainy season starts, they go back to Iloilo, Antique, or other towns in

Negros such as Victorias, Cadiz, and Sagay.

Page 25

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations in the Philippines

In Batangas,“sacadas” are “dayo” (migrant workers) or “Bisaya” (from the Visayas).These sacadas are generally

recruited by contractors. The contractor is responsible for bringing them back home. During the months of

January/February/March, the sacadas (tabaseros) arrive in Batangas. Many come from Quezon, Aklan, Antique,

and Bicol. More recently some of these migrant workers come from Mindoro.

In their place of origin, the sacada families live on subsistence level, normally getting only two (2) meals a

day consisting of rice, corn, or root crops. With no job opportunities, they sacrifice leaving their families to

work in the sugarcane fields.Those from the Visayas go to Pampanga and Tarlac first before going to Nasugbu,

Batangas. The number of Visayan migrant workers is declining because according to the contractors, many

sacada families are now beneficiaries of the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD’s)

Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps); some sacada workers opt to stay and no longer work in the

sugarcane fields.

FGD participants from Batangas viewed children of sacadas in a negative light: children as “madungis (dirty),

hindi naliligo (do not take a bath), malnourished, payat (skinny), kawawa (pitiful), may dalang kaldero at

itak (equipped with cooking pot and machete knife), Bisaya (from the Visayas), dayo (one who is coming

from outside their community), hindi marunong mag Tagalog (does not speak Tagalog), hindi nakikipaglaro

sa mga bata sa barangay (do not play with children in the community), sumasama sa grupo ng manggagapak,

nakayapak, at may towel (go with the sacadas, no foot protection/shoes/slippers, and with a towel), palipatlipat ng lugar ( moving from one place to another), laging hubad (oftentimes not fully clothed).

FGD sacada children participants from Aklan have associated the term “sacada” with the following: tubo

(sugarcane); mainit (hot weather); kailangang mabilis ang kilos (fast/quick moves/action); maagang gumigising

(early riser); mahirap na trabaho (tough job). A former sacada child described sacada work as “super mahirap

(super tough job), kulang na lang dugo ang umagos sa amin” (the work almost makes us sweat with blood).

Many sacada families associated sacada with “fast cash or ready cash” because of the practice of receiving

cash advances from a contractor or sugar plantation owner prior to their departure for work.

The Hacienda System and Roots of Sacada Work

The sacadas are better understood by looking back at history and checking the roots of their existence.

The origin of the hacienda system dates back to the colonial past of the Philippines. It was instituted by the

Spanish colonialist as an economic and political unit and was entrusted to loyal natives. The hacienda system

emerged with the formation of commercial haciendas. At that time, vast fertile lands tilled by peasants for

centuries were expropriated and converted into sugar and other export-producing agricultural estates (Ito

& Olea, 2004).The hacienda system can also be called a haciendero-sacada system which is a system of agrarian

relations (Corpuz, 1992).

Since the 1800s, the sugar industry has dominated the lives of sugar producing regions in the Philippines. An

increasingly high proportion of land was devoted to sugar rather than subsistence crops. This was the era

of the hacienda system in Negros. It has made many peasants more dependent and susceptible to hunger,

maltreatment and indebtedness (Billig, 2003).

The status of being sugar workers has been passed on from generation to generation. They do not own any

property or their “own” lives. What they have are the debts that have been handed down by their ancestors.

Page 26

Findings

The sugar workers are therefore landless, property-less and indebted. They have been tied to the hacienda

system and subjected to wage slavery and sub-human working and living conditions. The families of sugar

workers dwell in vast field of canes, in tents or makeshift bunkhouses that are covered with sacks or made

of old wood and branches of trees.

Historically, sacadas are “the farm workers in the sugar plantations of Negros.” They are described to be exploited

both by the hacienderos and the contratistas. The latter are labor contractors who earn money by serving as

middlemen with the sacadas as their “merchandise.” A Jesuit priest trying to unionize the sacadas elaborates

on how the system works as follows:

There are between 20,000 – 30,000 sacadas recruited every year who come mostly from Panay

island and brought to Negros during the milling season by contratistas. A contratista enters into a

contract with a haciendero binding himself to supply so many laborers. He gets an advance from

the haciendero usually an average of PhP46 per laborer. The money is given to the family of the

laborer to tide them over while the laborer is away. Although it is later on deducted from the sacada’s

earnings, it is sometimes given to him with interest. The sacada is also often cheated in food, in the

weighing of the sugarcane that he cuts, hauls and loads. The contratista gets a commission and he

earns over PhP1 per day per laborer that he supplies. Some of the contratistas are public officials,

town mayor and chief of police.

Slavery is a reality in an expeditious system of sugar plantation because of the peculiar labor needs of planting

and harvesting cane. The planting and harvest season is very tedious, expansive and busy and only a large,

well-disciplined labor force capable of toiling in the tropical heat can meet its demands. Sugarcane farming

tends to find a niche in regions where abundant labor could be turned to or coerced into doing field work

for low wages. Hence, production became associated with extremes in social structure: the very poor who

cultivate and cut the cane, and the estate owners and millers who control the process of converting canes

to sugar (Deduro, 2005).

The Sugar Industry

The Sugar Workers in Contemporary Times

Over the years, the working and living conditions of the sacadas have remained the same. The seasonal

nature of the sugar industry does not give job security to most of the farm workers and mill workers.

The government-mandated minimum daily wage for agricultural workers was at PhP175-250. However,

only very few work as regular workers and receive about PhP2,000/month. Other workers are

employed on an intermittent basis to weed and do other jobs and are paid an average daily wage of

PhP30 – PhP60.

Despite the payment of their wages, the farm workers continue to have a relationship of patronage with the

planter/landlord which intensifies the former’s exploitation. The planters remain to be responsible for the

upkeep of the workers. They run stores and sell overpriced foodstuff and other basic commodities to the

workers on credit.As a result of farm worker agitation during the sugar crisis in the 80’s, most haciendas now

allocate a portion of their land for rice cultivation, the harvest of which is then loaned by the planters to the

farm workers. The long list of debts is deducted from the wages of the farm workers, most often leaving the

workers still heavily indebted.

Page 27

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations in the Philippines

In 2003, government data showed that out of the 618,991.026 hectares planted with sugarcane,

49.41 percent was owned by about 1,807 planters (or 0.03% of the total 46,574 planters) whose land

ownership ranged from 50 hectares to 100 or more hectares. They also control the sugar industry’s 28

sugar mills and refineries. The same few also own the fertilizers, pesticides and farm implements businesses

(Deduro, 2005).

The sugar industry contributes about P76 billion annually to the Philippine economy from the production of

raw and refined sugar, molasses, and bio-ethanol. In addition, it supports foreign currency earnings through

exports of sugar under the US Sugar Quota Program and to other Asian countries and the world market

(Sugar Regulatory Administration-Department of Agriculture, 2014).

The share distribution of sugarcane plantations by island is as follows: Negros island - 51.22%; Mindanao 22.4%; Luzon - 15.32%; Panay - 7.23%; and Eastern/Central Visayas - 3.83%. Of the total sugar production

in the Philippines, 56% comes from Negros; 24% comes from Bukidnon (Mindanao), Panay, Leyte and Cebu

(Visayas); and 20% from Tarlac and Batangas (Luzon).

There are 28 operational mills in the country and 12 sugar mills (42%) are located in Negros. One of the

12 is Victorias Milling Corporation (VMC), known as the biggest refinery in the country and in Asia, and

the third largest in the world. Of all the sugar producing areas, Negros is dependent on the sugar industry

because of its monocrop nature. Negros has the most number of sugar workers in the country (310,000

out of 460,000 or 67%), and the most number of industrial sugar mill workers (18,000 out of 24,000)

(Deduro, 2005).

A Look at the Sugar Mill Districts

Following are the sugar mill industries in areas covered by the current research project.

Don Pedro Mill District - Western Batangas, Region IV-A (Sugar Regulatory Administration-Department

of Agriculture, 2014)

Don Pedro mill district covers the western portion of Batangas and some municipalities in Cavite, Laguna and

Quezon. The mill district has seven planters’ associations that are affiliated with the Don Pedro Mill District

Development Council Foundation Inc. (Don Pedro MDDCFI). Don Pedro MDDCFI is a SEC-registered

foundation created in 2001.The mill district has 69 units of tractors owned and operated by private planters

and the MDDCFI. The MDDCFI successfully operated its tractor pool through the DA-SRA Sugar ACEF

program and was able to serve the tractor needs of the small farmers in the district.

The total plantation area in the district was 14,186 hectares in CY 2012-13 with a total sugarcane and sugar

production of 740,455 MT and 1,433,332 LKg bags,respectively. Don Pedro mill district is composed of 6,187

farmers where 98 percent are small farmers, both Agrarian Reform Beneficiaries (ARBs) and non-ARBs.

The hectarage cultivated by small farmers in the mill district is proportionate to the number of farmers

and comprises an aggregate plantation area that is larger compared to those of the large farmers. Sugarcane

plantations in the mill district are traditionally owned by small farmers.

The sharing ratio in the mill district is 65 percent in favor of the planters and 35 percent for the miller. Sugar

production in crop year 2012-13 contributed to only 2.9 percent of the national production.

Page 28

Findings

Sacada cooking area, Cadiz, Negros Occidental

Children of sacada families, Kabankalan, Negros Occidental

Page 29

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations in the Philippines

Sacada housing inside view after workers left, Kabankalan, Negros Occidental

Page 30

Findings

The mill district has one sugar mill, the Central Azucarera Don Pedro Inc. (CADPI). The canes milled by

CADPI had less sugar content than the averages in Luzon and the country as a whole. Wage rates in Don

Pedro mill district was usually P180/day but could vary depending on the farm activity.

There are two operational block farms in Don Pedro mill district both situated in Nasugbu, Batangas. These

are Kamahari Multi Purpose Cooperative (MPC) with 40 beneficiaries and a total farm area of 32.5 hectares,

and Damba Multi Purpose Cooperative (MPC) with 40 beneficiaries and a total farm area of 33 hectares.

The block farms were organized by the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) and assisted by the Sugar

Regulatory Administration (SRA) on sugarcane farming technologies and capability building.

Cost of production per hectare for small farms range from PhP30,000 to PhP50,000; for medium-size farms

from PhP60,000 to PhP70,000; and for large farms from PhP80,000 to PhP100,000. Around 10-15 percent of

the plantations in the district are leased to private financiers or large planters.

Balayan Mill District - Eastern Batangas, Region IVA

Balayan Mill District covers 22 municipalities of eastern Batangas. The mill district has an area of 16,273

hectares and had a sugar production of 1,995,306 LKg bags in crop year 2012-13; this was 4.05 percent of

the total national sugar production. The sharing system adopted was 65 percent for planters and 35 percent

for millers. Farm yield was 64.55 TC/Ha and 122.61 LKg /Ha while average sugar yield for the crop year was

1.90 LKg/TC. Balayan has the highest farm yield so far among the Luzon mill districts. It is composed of 3,887

farmers, 92 percent of whom are small farmers, ARBs and non-ARBs.

Cost of production in the district ranged from PhP50,000 to 100,000 per hectare. Financing for farm

operations were sourced from the Land Bank of the Philippines, rural banks and planters cooperatives.

Interest rates usually ranged from 6 percent to 10 percent depending on the track record of the farmer or

cooperative. Around 20 percent of the farms in Balayan mill district are leased to private individuals at the

rate of PhP7,000 - PhP12,000 per hectare.

The mill district has to deal with certain challenges to remain cost-competitive. There is scarcity of farm

laborers in the mill district so the district has to import cane cutters from Negros; labor costs tend to be

high. To address the labor shortage problem, mechanizing farm operations especially the harvesting and

loading operations has become an urgent need in Batangas. Removing excess cane trashes in the fields during

harvesting is also a problem in the district.

Lopez Mill District – Negros Occidental, Region VI

Lopez mill district covers Escalante City, a portion of Cadiz City and Sagay City of Negros Occidental. In crop

year 2012-13, the mill district had a total sugarcane area of 13,010 hectares with a total sugar production of

1,522,170 LKg bags, which constituted 3.09 percent of the national production. Sugar sharing scheme of the

mill district is 70 percent for planters share and 30 percent for millers. Its cane yield was 60 TC/Ha, a sugar

yield of 117 LKg/Ha and 1.95 LKg/TC. In crop year 2010 - 2011, it recorded a total of 492 farmers, of whom

58 percent were small farmers.

The planters in the mill district project said that due to land reform, sugar production will decline because

the ARBs have no financial and technical capability to operate sugarcane farms.

Labor shortage is another problem in the mill district. A government financing scheme with counterpart

funding by the planters cooperatives for the acquisition of cane loaders and harvesting equipment is needed.

Page 31

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations in the Philippines

The labor rates per farm activity in the mill district could range from Php1,295 per hectare (cultivation) to

Php12,000 per hectare (land preparation). Cutting and loading cost Php 5,385 per hectare while hauling costs

Php 7,313 per hectare.

Child Laborers in Sugarcane Plantations

The Philippine DOLE defines child labor as:

“the illegal employment of children below the age of fifteen (15), where they are not directly

under the sole responsibility of their parents or legal guardian, or the latter employs other workers

apart from their children, who are not members of their families, or their work endangers their

life, safety, health and morals or impairs their normal development including schooling. It also

includes the situation of children below the age of eighteen (18) who are employed in hazardous

occupations.”

Children above 15 years old but below 18 years of age who are employed in non-hazardous undertakings,

and children below 15 years old who are employed in exclusive family undertakings where their safety,

health, schooling and normal development are not impaired, are not considered as “child labor” under the

law (International Labor Organization (1998).

Based on the 2000 survey of the ILO and National Statistics Office (NSO) and studies by the Bacolod Citybased research group Center for Investigative Research and Multimedia Services (CIRMS), around four (4)

million or 16.2 percent of the 24.9 million Filipino children aged 5 – 17 years are working.

The CIRMS study shows that 64 percent of working children in Negros are rural-based. Majority (26%) are

working in sugarcane plantations doing weeding, plowing, fertilizing, cane cutting and hauling during harvest

season. On the other hand, 14 percent work in rice/corn farms and orchards; 11 percent in commercial

fishing as helpers and divers in trawls, haul boats, fishing boats and fishponds; three percent in various rural

odd jobs like charcoal making, woodcutting, vending, small-scale mining and serving as a helper in public utility

jeepneys; and one percent in domestic work (Deduro, 2005).

The CIRMS study also reveals that child labor within the sugar hacienda system has its own particularities.

Poverty pushes children to work but the CIRMS study further says that the exploitative character of the

sugar hacienda system also contributes to children working.

Sugar landlords do not only rely on the parents of the family but on every “productive family” residing in the

hacienda. This is proven by the fact that 92 percent of the sugar working family respondents said that “their

children do not just work as replacements, but as regular working force just like the parents. And for decades, their

families have been treated by their employers as a productive unit which has to render service regardless of their age

and gender.”

Some children go with their parents who work as sacadas. With their parents having only five (5) months of

work in the hacienda, going to the local school for these children is not possible. They spend their time as

additional workforce and have the sugarcane fields as their playground (Remollino & Aznar, 2004).

Page 32

Findings

But just like any other children, sacada children, when given the opportunity to study can also transform their

lives, as in the case of Carlos R. Gerogalin, Jr., who was a consistent scholar at West Negros University. He

graduated Summa Cum Laude, the highest honors given by the University (Malo-oy, 2012).

Responding to Sacada Needs

The DOLE is the primary government agency responsible for enforcing child labor laws. The agency also

leads a regional mechanism for rescuing children who work in abusive and dangerous situations through

the Rescue the Child Laborers or Sagip Batang Manggagawa (SBM) Quick Action Teams. SBM is composed

of government law enforcement agencies, local governments, the business community, unions, and nongovernment organizations (NGOs). SBM receives reports of possible instances of child labor in the formal

and non-formal sectors and coordinates an appropriate response among the relevant agencies for each case.

As needed, children are referred to the DSWD for rehabilitation and reintegration. In 2012, SBM rescued

223 child laborers across nine (9) regions.

Child labor is included in the following national development agendas: Millennium Development Goals (20002015); Education for All National Plan (2004-2015); Basic Education Reform Agenda; and UN Development

Assistance Framework (2012-2018). In addition, the government launched the national Child Labor-Free

Philippines campaign and the Child Labor-Free Barangays (Villages) program, and developed a new national

Convergence Plan to reduce hazardous child labor.

The Government has primary policy instruments to prevent and eliminate child labor. The Philippines

National Strategic Framework for Plan Development for Children 2000-2025 also known as “Child 21”, sets

out broad goals to achieve improved quality of life for Filipino children by 2025.

The Tripartite PPACL Strategic Framework lays out the blueprint for reducing the incidence of child labor

by 75 percent. The PPACL identifies five strategic approaches to prevent, protect, and reintegrate children

from the worst forms of child labor in order to achieve the goal. To translate this strategic framework into

action, the Implementation Plan (2011-2012) identifies concrete objectives such as improving the access of

children and their families to appropriate services to further prevent incidence of child labor and reintegrate

former child laborers.

In June 2012, the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) launched the Batang Malaya Child Labor-Free

Philippines campaign. Campaign objectives include: the institutionalization of the Survey on Children to

be regularly implemented by the Government; mainstreaming child labor into local development plans;

adding child labor elimination as a conditionality in conditional cash transfer programs; strengthening the labor

inspectorate to monitor child labor; improving enforcement of Republic Act No. 9231; and strengthening the

NCLC through a legal mandate, budget, and dedicated secretariat.

Integrated Services for Migratory Sugar Workers (MSW) Project (I-SERVE SACADAS)

(DO No.108-10 (series of 2010)

The DOLE issued Department Order No. 08-10, Series of 2010 - Guideline on the Implementation of the

I-SERVE SACADAS Project on 3 November 2010.

Page 33

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations in the Philippines

The I-SERVE SACADAS is an integrated approach aimed at changing the socio-economic conditions of

MSWs by augmenting their income, ensuring compliance of employers/contractors to protective and welfare

policies and providing them opportunity to participate in policy making processes so that their problems

may be addressed appropriately. This project took effect on 3 November 2010 and is implemented by the

Bureau of Workers with Special Concerns (BWSC) and concerned DOLE Regional Offices (DOLE ROs) in

partnership with the sugar producers, local government units (LGUs), other government agencies, NGOs,

people’s organizations (POs) and workers’ organizations.

The approach is piloted in selected communities in Regions 5, 6 and 7, specifically in Camarines Sur, Aklan,

Negros Occidental, Negros Oriental, and Antique with an initial DOLE funding allocation of PhP10,700,000.

The project consists of five (5) interventions, namely: assistance for livelihood formation and/or enhancement,

alternative employment, skills upgrading, health care, and worker empowerment through participation in

decision making processes. The project also intends to strengthen the SBM Program for child laborers in

sugar plantations and supports advocacies aimed at eliminating the worst forms of child labor under RA 9231

(Villanueva, 2011).

In 2012, the President tasked the Human Development Cabinet cluster, led by DOLE and DSWD, to develop

a Convergence Action Plan, called HELP ME, to reduce the worst forms of child labor by 2016 under the

PPACL. The directive included a funding allocation of $220,000,000 over four years for implementation,

from 2013 to 2016. The Convergence Action Plan is designed to remove 893,000 children from hazardous

child labor across 15,568 target barangays. The HELP ME plan focuses on outcomes that include a multilevel

information system, more accessible education and livelihood services, child labor agendas mainstreamed

in policy development at all levels, a compilation of policies and laws, and strengthening of enforcement

including prosecution of child labor offenders. HELP ME was launched in January 2013.

Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps)

The DSWD implements the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program to improve the livelihoods of vulnerable

families and children and to reduce child labor. The agency provides cash transfers to households, conditional

upon their children’s achievement of a monthly school attendance rate of at least 85 percent and regular

medical checkups and immunizations. In 2012, the budget was increased to $960,000, from $570,000 in 2011,

benefiting 3.1 million households and 7.4 million children through age 14.

In January 2013, DOLE announced that the 4Ps was expanded and modified through the Conditional Cash

Transfer Program for Families in Need of Special Protection to specifically target households of child sacadas.

Collaboration between Government and Non-Government Organizations

On July 11, 2014, a Memorandum of Agreement was signed in Balayan, Batangas among the DOLE, ABK3 LEAP

Partners i.e., Educational Research and Development Assistance (ERDA) Foundation, ChildFund Philippines

and Sugar Industry Foundation, Inc. (SIFI), together with other partners, namely Department of Interior and

Local Government (DILG), Department of Education (DepEd), Provincial Social Welfare and Development

Office (PSWDO), Provincial Health Office, Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA),

Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) Calabarzon, and Philippine

Information Agency (PIA).This initiative envisions the localization of the Philippine Government’s Convergence

Program through the barangay-based HELP ME Strategy (Health, Education, Livelihood, Prevention, Protection,

Prosecution, Monitoring, and Evaluation), setting up the Child Labor Monitoring System (CLMS), and inclusion

Page 34

Findings

of ABK3 partner barangays in the Child Labor Free Barangays campaign of DOLE. It is hoped that the 12

ABK3 partner barangays will be supported in their journey to becoming Child Labor Free Barangays, and that

through the CLMS, child labor situation is regularly tracked and updated (http://www.abk3leap.ph/batangasbrings-child labor-convergence-program-to-the barangays, November 12, 2014).

On February 13, 2015, DOLE IV-A rescue operation saved 12 child laborers in Brgy. Pooc and Brgy. Sampaga

in Balayan, Batangas.The operation was geared towards battling the growing incidence of child labor in Region

IV-A and put into action DOLE IV-A’s formulated Child-Labor Rescue Plan. The operation was successfully

executed by DOLE-IV A Rescue Team led by its Regional Director Ma. Zenaida A. Angara-Campita. It was

backed up by security forces of the Regional Intelligence Division (RID) IV-A, composed of 40 armed

policemen headed by Colonel Noel Nuñez, accompanied by the DSWD IV-A represented by Ms. Lucila A.

Bacay, and media representatives for coverage and documentation.

The workers did not have birth certificates because, according to the contractor, only barangay clearances

and bio-data were required for recruitment process. Hence, the actual ages of the 20 alleged minor workers

were validated through dental examination. Out of the 20, 12 were confirmed minors with age 14 as the

youngest. They were turned over to the care and custody of DSWD IV-A and were temporarily housed

in the DSWD-accredited shelter located in San Antonio, Quezon. The two (2) contractors responsible in

recruiting the minors were found to have been registered and were granted the authority to recruit under

the Department Order No. 18-A. However their Certificates of Registration may be cancelled or revoked

after due process if they engage in child labor (Prieto, 2015).

Batangas is one of the first to pioneer the localization of the Convergence Program, bringing together important

stakeholders to end child labor through community-based support to children, families and communities. In

2012, the sugar industry stakeholders in Batangas, in partnership with DOLE, DepEd, DILG, DSWD, and civil

society organizations formulated and passed a Voluntary Code of Conduct for the Elimination of Child Labor

in the Sugar Industry in Batangas, the second of its kind in the Philippines, the first one being in Bukidnon.

Sacadas in Receiving Provinces: Batangas, Negros Oriental and Negros Occidental

Profile of Adult Sacadas

A typical sacada respondent is male (95% of 168), elementary undergraduate (54%), and had worked as

sacada for an average of 11 years (or ranging from less than one month to 53 years).

Slightly more than half (51%) of them hail from Negros Oriental while the rest come from Negros Occidental

(19%), Aklan (13%) and other provinces in the Visayas (19%). A few others come from different parts of

Luzon (15%) while a small fraction (1%) come from Mindanao.

Of the 168 respondents, slightly more than two-fifths (43%) were unmarried and have no children. The rest

have children ranging from one (7%) to nine (1%) – or with an average of two children. Six (6) out of 10

respondents in Negros Occidental have no children. Those who have children (95 of 168 or 57%) have left

them in the care of their spouse (83%) in their home province.

Eight (8) out of ten (85% of 168) survey respondents worked as sacada to be able to help their families. Some

others have varied reasons ranging from wanting to rebuild their houses that were destroyed by typhoon Yolanda

Page 35

Migration Patterns of Sacada Children and their Families in Selected Sugarcane Plantations in the Philippines

(2%), being with working husband or children (5%), to having a higher income or wanting to have a better life (11%).

When asked whether they had worked before as sacada apart from their “current workplace”, seven out of

ten (73% of 168) answered affirmatively – with the highest response coming from those in Negros Oriental

(93%), followed by those in Negros Occidental (65%), and Batangas (55%). Many of those in Batangas (48% of

29) and Negros Oriental (25% of 59) had worked before in Pampanga while close to a third (32% of 34) of

those in Negros Occidental had worked in the same province.

Four out of ten (43% of 168) were hired as sacada by a “contractor”. According to several respondents, the

contractors came from Aklan (21% of 72), Tarlac (15%), Negros Occidental (18%), Negros Oriental (15%),

and Antique (13%). Small fractions (ranging from 1% to 7%) came from other parts of the Visayas (Iloilo),

Luzon (Batangas, Quezon) and Mindanao (1%).

The place of origin of the contractors varied across the respondents.The contractors of sacadas mainly came

from Aklan (65% of 23 for those in Batangas), Tarlac (61% of 18 for those in Negros Oriental), and Negros

Occidental and Antique (39% and 29%, respectively, for those in Negros Occidental).

Close to two-fifths (39% of 72) mentioned that the contractor was well known in their community as

providing work opportunity to the residents, while others were introduced to the contractor by a relative,

friend or neighbor (32%). Almost a fifth (19%) said that the contractor came to their community to ask who

among them would be interested to work as sacadas.

A big majority (83%) said they did not pay anything to the contractor while the few others said otherwise

(6%) or did not respond (11%). The four respondents who answered affirmatively said that they paid the

contractor 25 percent of their income at the end of their contract.

Nature of Involvement in Sacada Work

Other household members who worked in the sugarcane plantation were the respondents’ spouse (12%

of 168); their children aged 17 years and below (9%) and 18 years and above (1%); and other relatives (2%).

These respondents mainly worked in Batangas and lived in other Luzon provinces like Quezon and Bicol,

where transportation is more accessible.

The sacadas were mainly involved in harvesting and cane cutting (69% of 51 in Batangas; 59% of 63 in Negros

Oriental), and hauling of sugarcane (56% of 52 in Negros Occidental). Few others (ranging from 1% to 16%)

were involved in a combination of activities such as harvesting, hauling, preparing food, cleaning, applying

fertilizer, weeding, burning, sugarcane peeling, sowing, and transporting sugarcanes to the milling venue. The

sacadas worked 10 hours (Negros Oriental and Occidental) or 11 hours (Batangas) on the average per day,

and mostly six (6) days a week. Majority (58%) said they have no savings from sacada work.

Family Relationship

The main mode of communication between sacadas and their families was through text messaging or mobile

phone calls (87% of 54), ranging from thrice a week (39%) to once a month (24%). Few others either

communicate more frequently (13%, every day) or seldom (7%, every other month).

Nine out of ten (91% of 54) sacadas claimed to have provided allowances to their families, on the average of

PhP1,348 per week.

Page 36

Findings

Family Situations in Home Province and Sacada Workplace

Sacada respondents were asked to describe their living conditions at their place of origin and their current

workplace. Their responses are shown below:

Table 2: Sacadas’ Living Conditions in Home Province (HP)

and Current Workplace (CW)

Living conditions

Far from the town proper;

difficult to reach.

Many people are unemployed.

Many people do not have anything

to eat because of poverty.

Many children could not go to

school.

Lack basic facilities (school,

health center, etc.)

Lack basic services (education,

health, etc.)

Poor road condition