HERZBERG'S DUAL-FACTOR THEORY OF JOB

advertisement

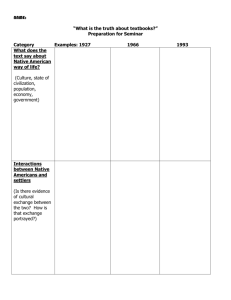

HERZBERG'S DUAL-FACTOR THEORY OF JOB SATISFACTION AND MOTIVATION: A REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE AND A CRITICISM ROBERT J. HOUSE and LAWRENCE A. WIGDOR Bernard M. Baruch School of Business and Public Administration In. 1959, Herzberg, Mausner and Snyderman reported research findings that suggested that man has two sets of needs: his need as an animal to avoid pain, and his need as a human to grow psychologically. These findings led them to advance a "dual factor" theory of motivation. Since that time, the theory has caught the attention of both industrial managers and psychologists. Management training and work-motivation programs have been installed on the basis of the dual-factor theory. Psychologists have both advanced criticisms and conducted substantial research relevant to the dual-factor theory. The purpose of this paper is to review the theory, the criticisms, and the empiric investigations reported to date, in an effort to assess the validity of the theory. Whereas previous theories of motivation were based on causal inferences of the theorists and deduction from their own insights and experience, the dual-factor theory of motivation was inferred from a study of need satisfactions and the reported motivational effects of these satisfactions on 200 engineers and accountants. The subjects were first requested to recall a time when they had felt exceptionally good about their jobs. The investigators sought by further questioning to determine the reasons for their feelings of satisfaction, and whether their feelings of satisfaction had affected their performance, their personal relationships, and their well-being. Finally, the sequence of events that served to return the workers' attitudes to "normal" was elicited. In a second set of interviews, the same subjects were asked to describe incidents in which their feelings about their jobs were exceptionally negative—cases in which their negative feelings were related to some event on the job. 369 370 PERSONNEL PSYCHOLOGY Herzberg and his associates concluded from their interview findings that job satisfaction consisted of two separate independent dimensions: the first dimension was related to job satisfaction, and the second dimension to job dissatisfaction. These dimensions are not opposite ends of the same continuum, but instead represent two distinct continua. High satisfaction is not in the main brought about by the absence of factors that cause dissatisfaction. Those job characteristics that are important for, and lead to, job satisfaction but not to job dissatisfaction are classified as "satisfiers," while those that are important for, and lead to, job dissatisfaction but not to job satisfaction are classified as "dissatisfiers." A few job characteristics functioned in both directions. According to the theory, the satisfiers are related to the nature of the work itself and the rewards that fiow directly from the performance of that work. The most potent of these are those characteristics that foster the individual's needs for self-actualization and self-realization in his work. These workrelated or intrinsic factors are achievement, recognition, work itself, responsibility, and advancement. A sense of performing interesting and important work (work itself), job responsibility, and advancement are the most important factors for a lasting attitude change. Achievement, more so than recognition, was frequently associated with the long-range factors of responsibility and the nature of the work itself. Recognition that produces good feelings about the job does not necessarily have to come from superiors; it might come from peers, customers, or subordinates. Where recognition is based on achievement, it provides more intense satisfaction. The dissatisfaction factors are associated with the individual's relationship to the context or environment in which he does his work. The most important of these is company policy and administration that promotes ineffectiveness or inefficiency within the organization. The second most impotant is incompetent technical supervision—supervision that lacks knowledge of the job or ability to delegate responsibility and teach. Working conditions, interpersonal relations with supervisors, salary, and lack of recognition and achievement can also cause dissatisfaction. HOUSE AND WIGDOR 371 The second major hypothesis of the dual-factor theory of motivation is that the satisfiers are effective in motivating the individual to superior performance and effort, but the dissatisfiers are not. In his most recent book, Herzberg (1966, p. 75) advances the following analogy to explain why the satisfier factors or "motivators" affect motivation in the positive direction. When a child learns to ride a bicycle, he is becoming more competent, increasing the repertory of his behavior, expanding his skills—psychologically growing. In the process of the child's learning to master the bicycle, the parents can love him with all the zeal and compassion of the most devoted mother and father. They can safeguard the child from injury by providing the safest and most hygienic area in which to practice; they can offer all kinds of incentives and rewards; and they can provide the most expert instructors. But the child will never, never learn to ride the bicycle— unless he is given a bicycle! The hygiene factors are not a valid contributor to psychological growth. The substance of the tasks is required to achieve growth goals. Similarly, you cannot love an engineer into creativity, although by this approach you can avoid his dissatisfactions with the way you treat him. Creativity will require a potentially creative task to do. Criticisms of the Two-Factor Theory The theory has been criticized on several grounds: first, that it is methodologically bound; second, that it is based on faulty research; and third, that it is inconsistent with past evidence concerning satisfaction and motivation. Each of these criticisms will be reviewed here. Methodological Bounds of the Theory. Vroom (1964) has argued that the storytelling critical-incident method, in which the interviewee recounts extremely satisfying and dissatisfying job events, accounts for the associations found by Herzberg et al. and that other methods are required to adequately test the theory. It is . . . possible that obtained differences between stated sources of satisfaction and dissatisfaction stem from defensive processes within the individual respondent. Persons may be more likely to attribute the causes of satisfaction to their own achievements and accomplishments on the job. On the other hand, they may be more likely to attribute their dissatisfaction not to personal inadequacies or deficiencies, but to factors in the work enviroiunent; i.e., obstacles presented by company policies or supervision. (Vroom, 1964, p. 129) "People tend to take the credit when things go well, and enhance their own feeling of self-worth, but protect their self- 372 PERSONNEL PSYCHOLOGY concept when things go poorly by blaming their failure on the environment" (Vroom, 1966, pp. 7, 8). He further states, "If you grant the assumption about the way in which biases operate, it follows that the storytelling methods may have very little bearing on the actual consequence of managerial practice." (Vroom, 1966, p. 10). Faulty Research Foundation. Not only has it been argued that the theory is method bound, but it is also argued that the research from which it was inferred is fraught with procedural deficiencies. The most important criticism involves the utilization of Herzberg's categorization procedure to measure job dimensions, the satisfiers and "hygiene factors." The coding is not completely determined by the rating system and the data, but requires, in addition, interpretation by the rater. For example, the dimension of supervision encompasses, among others, the categories: (a) "supervisor competent," (b) "supervisor incompetent," and (c) "supervisor showed favoritism." The three classifications all require an interpretation of the supervisor's behavior. If the respondent offers the evaluation, no interpretation by the rater is required. However, if the subject merely describes the supervisor's behavior, an evaluation by the rater is necessary. The necessity for interpretations of the data by a rater may lead to contamination of the dimensions so derived. Employing one of Herzberg's own incidents to illustrate the dimension of recognition, Vroom (1964) pointed out the way in which the dual-factor theory may contaminate the coding procedure. The dimensions in the situation can quite possibly refiect more the rater's hypothesis concerning the compositions and interrelations of dimensions than the respondent's own perceptions. A more objective approach, to minimize the possibility of learning more about the perceptions of raters than those of interviewees, would be to have the respondents do the rating and perform the necessary evaluations (Graen, 1966). Second, and closely related to the first methodological problem, is the inadequate operational definitions utilized by Herzberg and associates to identify satisfiers and dissatisfiers. Numerous critics (Malinovsky & Barry, 1965; Burke, 1966; Ewen, 1964; Dunnette, 1965) have questioned the mutual HOUSE AND WIGDOR 373 exclusiveness of these dimensions. Malinovsky and Barry (1965) reported that it is possible that correlations between motivator items and between hygiene items in the evaluations of factors resulted from response-set effects—the tendency of the workers to respond in the same manner to like-worded statements. The original study has also been criticized because it contains no measure of overall satisfaction (Ewen, 1964). However, such a measure is important if a factor is to be called a satisfier or dissatisfier. There is no basis for assuming that the factors described as hygiene or motivators contribute to respondent overall satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Smith and Kendall (1963) have shown that a worker may dislike some aspects of his job, yet still think it is acceptable. Similarly, workers may dislike the job despite many desirable characteristics. Smith and Kendall (1963) propose that job satisfaction is a function of the perceived characteristic of a job in relation to an individual's frame of reference. A particular job condition can be a satisfier or dissatisfier. Other procedural criticisms concern the lack of reliability data for the critical-incident method, and the fact that the research was not based solely on current satisfaction with a presently existing job situation. As a result, there is no control over the sampling time for the data, and no basis for drawing inferences about the relative contribution of various job factors to overall job satisfaction. Inconsistency With Previous Evidence. If the dual-factor theory were correct, we should expect highly satisfied people to be highly motivated and to produce more. Based on a rather exhaustive review of the empiric research up to 1955, Brayfield and Crockett (1955) concluded that one's position in a network of relationships need not imply strong motivation for outstanding performance within the system, and that productivity may only be peripherally related to many of the goals toward which the industrial worker is striving. Herzberg et al. (1959) cited 27 studies in which there was a quantitative relationship between job attitude and productivity. Of these, only 14 revealed a positive relationship. In the remaining 13, job attitudes and productivity were not related. In 1964, Vroom examined 20 studies dealing with strength between job satis- TOTALS PERSONNEL o PSYCHOLOGY CO m 5-1 374 1-1 Cd fk It X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X K • oi i X Finn Supr. X X X X X Pre X Fem. Assem. X X il X X Mfg. Supi HERZBERG o X X X X X X X X X XI Xi X SALE M X X Cfl urs. Eng. Sci. K M J; < ^1 X I XI a S XI XI XI I X XI XI X XI X X XI XI H Prof. Women ^ > X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X Eng. WALT SCHfl < X X X X X X X I < X X X X X 1 1 O '3 •< M i s ll •§ o 11 II 02 •3 . ii X X lterper sonal relat.-]peers 1 0. Pol. Adm. 1 X X -uon [GATOR 1 n ehievei tion elt ibility M . m < Popul ation Fac tor ^ ^ •3 . 11 375 HOUSE AND WIGDOR faction and job performance. Seventeen studies revealed a positive relationship with a medium correlation of .14, while 3 studies revealed a negative relationship. At the present time, there seems to be general agreement among most researchers that the effect of satisfaction on worker motivation and productivity depends on situational variables yet to be explicated by future research. Furthermore, as Friedlander (1966a, p. 143) reported, no data are presented by Herzberg to indicate a direct relationship between incidents involving intrinsic job characteristics and incidents containing self-reports of increased job performance. According to the Protestant ethic, it is conceivable that self-reports of increased job performance may be nothing more than moral justification for increased job enjoyment. Vroom (1966, p. 11) summarizes these arguments succinctly: "In discussing the administrative implication of his findings, Herzberg loses sight of the distinction between recall of satisfying events and actual observation of motivated behavior. He appears to be arguing that the satisfiers are also motivators; i.e., that those job content conditions which produce a high level of satisfaction also motivate the person to perform effectively on his job." If one reflects on the kinds of conditions necessary for productive work, it becomes quite clear that motivation is only one of them. Clearly, when working conditions, the quality of TABLE 2 Frequency of Reports for Satisfiers And Dissatisfiers Out of Total Number of 1,ZZO People in Six Studies Reported by Herzberg (1966) Factor Achievement Recognition Advancement Responsibility Work itself Policy and administration Supervision Work conditions Relations with superior Relations with peers Satisfier Dissatisfier Total Number of People 440 309 126 168 175 55 22 20 15 9 122 110 48 35 75 337 182 108 59 57 1,220 1,220 1,220 1,220 1,220 1,220 1,220 1,220 1,220 1,220 376 PERSONNEL PSYCHOLOGY a IS "i a •a O ^1 o o c O .2 d be CO 0) to ^H _J "^ O ••3 o « "!i S 2 o ^S 5s •-• 03 ., 2 s '^ •^ 2 s a o o o ^5 ^ C O (^ ^ ft M S •' s m .g .2 -;3 ..D 03 ale O ':3 --^ bo •S o -o <D o bU O a"-. 03 p! 02 .^ g ft -a 03 indu 03 and o o 3e ege 03 ^ Qi ployed female' W 2 t. -S 3 - 5 e 03 bo '3 £ fe » 3 o W a •Si aj "2 "S 3 EH O a §.° ' ft-r +s 03 •^ ^ m so g ° 05 o c _< ' ^ Ilil! I - - S lisp a o 03 fJ^ • r/^ 02 (H 1 TO T3 s a 73 ca o CM"^ a O oS 03 ^ 1 m O o " 0. -a g r2 §- • a 3 -^ s^s 2 °5 3 T3 £ -3 - ^ S . 2 Ills O O CO 3 I £ I gII 03 03 « "S O<D bC 3 m T3 3 Q ca £ rS d •'^ C3 03 377 HOUSE AND WIGDOR ie £ -a T3 B fi » 3) o3 m 03.. "^ gi £ a^l s m I ^I US o ; P o3 b .il rt J. =a » § § » ^ - a •^ g O :=i g 02 I 03 3 -2 >• bc ^•3 o fi P d " 02 O '+3 c3 m S g -o 'oao wen. - ^ -*^ 3 02 CO CO 03 fi" o W o 378 PERSONNEL PSYCHOLOGY 2 m K X 02 02 ' J3 'i^ o & m C S 03 CO 1| l l 03 "a om CO ts "I & CO ^ - ^ a^-gl^ a; -.zi m 5 T3 ^ " •> - s g § I HOUSE AND WIGDOR ft « ' III O o 379 -a <2 03 03 O 2 0^ an Oi bC c fi a QJ Oi CO 33 g 1! Oi 1 o 02 Qi 3 'g •2*'o cr ' > . ^ "5 O '< w P fi 2 SE "3 ',3 O5 fi .fi M 1 s bC C ft «) c fi 03 o j2 a CO fi ft UH K "3 Oi "^ 13 o -(^ 3 •d o3 M Oi bC Oi bt fi d . 1 . - , % Ci 03 CO P! •2 01 *-^ Findings b satisfaction was self-ac0 Herzberg, the category of -ion was s imilar to his achievement asibilit-if categories. Major source itis:faction was action of supervisors b e .on text, each of which did not conto job sat isf action. we] :e equa!Ily well satisfied with both ator an d hygiene aspects of their motiv ators contributed signifirerall satisfaction than did urc 03 -^-fi" CD ilth depends to a major deevelopi ng an orientation toward -actiual iz ation , achievements, responsid goal-directed effort. Improved tained 1ligher motivator and lower ores thim the unimproved. College obtaine d higher motivator and iene sc ores than the two schizo 0 '^ actii 02 "o XG o ai £ CO OJ ''3 3 13 Oi Ci 1 a tH I a g zed 'O ^ i> o '-*3 ai • i "S o '> tH bo !3 C:D 4^ bC X *^ o .13 CO tH tH g o ^fi ft ft 2- £ Stu -£ £ o OJ i -a£ •2 IT '3 O £ S o g tie: 3 o E>2 <H-< •s ked H o ced-ch ure ; ivator "S o:j 03 fi with 1'our iene : satis fac- S ,fi S Jtisfac 1, four overall ponde: IS m atings 0 motivai tors, ai tion on job )-item questio choice-] Oi bJ3 s o -oni >—1 to o 69 su tH Oi bC-O o ;i96 3 H ai llin (fl <D itionn aire and rlon- Ci +^ coll Oi +-> cn the tD iing at an effortful task was e the approach motivation of the ject 0 participate in future activities mpting to improve motivation by iks a c ontextual relationship rethe motiva.tion to one of avoidance of ire actiivi ties. CD O wo: fore ,-t [ mot: J fi - 800 0 -o iterpose asks b and aft tion. M eas ured e vening iables ilatedn ining student ies of f penmei ontent a yses oi on rela1 ; satisf satisfyi experii • 59) h-t tud nts o UI.lf 1 Colle HH Procedu I I ject 380 PERSONNEL PSYCHOLOGY go bO sa oa o bC Xi '3 1i PH is § ft .a H - J tH C2 B fi bC CO ti ^ o S bo ai s CO a •g Q 0 0 1 -a .a ca n 3 CO "3 fi t-i 0 03 .3 03 W Ci 0 1 ft ft o3 £H 1 e CO ^ ^a ciai 1 CO fi ft 3 09 a 0 ^^ ca u ai 0 fli '•3 g •w a •s '3 § tH _o 0 fi tH 03 _Ci a J 01 bf) -S CO I—( 02 J "13 -2 Oi a 03 1 3 CO w fi a ai pH a 0 • 0 0 3 fi .a a -S very in coi re st ated r subjects ition to be 'hile t;hose 5h in sing level 3ati sfacti re not t inion 3 tors laly- 5 be- etors seen o3 0 0 1 - H '+3 ai 03 •3 ?^ Oi cS > > fi '-3 0 '"..'SD '« ..a .S ai fi b£ J3 .SS ag erzb .E: ir and larger v resp ond ents' overall 1( ions of j ob sat isf long separate ibute ract i variety of wa :tract from the first e composed of Bms. Overall th hygiene anc eristics grou] otiva tor- hygiene dich 5rg motivator Herzberg me rators and hyj different job . The female fferer -om the four 1 a sex factor. I Lt from the he lurly ale assembler stmg ob-level facto ai 03 0 Ui 0 analys o3 ai atti1 c a 1 coniDrib'uting to negai 0 isfac 1 frequency b; n the overall proportion of ensions (moti Ci lalysis f 40-ite nnaire tor ai tH ?ith "fi e atti ith ei )sitio motivations. 0 ca oS ontei type a" •^ 'S cc o3 1 to OVi /•oida 3 "^ ai actor orde ques moti item ? 2 .a 03 spon tH ctors sohii CQ XI uT a 0K le sci eers, ervis ians. ourb ft '—^ . 1 outh .5 03 0 0 watc <! 2 i96 qo. 1 Xi OQ i conce rni ;ati ai mal e mai .2 M C3 fluet a of 4^ a C5 (196 -a .2 «*.H a ap >IS 03 s bC tterr -end C3 aotivatlOB 'S a 0 ihkir ai a -a xi I and I fi SS. bO seal I significant t« ligh in motiva a approach mo giene oriental a 2 jectf ontei Oi 0 ventor^ loice-m oti indu tH engi neeri; toward £ ai The Han .ttitu situi ai •I £ ric elf .2 _o a '.^ a * | | .a ^^ ll a^ Q 0 ll 1-5 ^co '> -M a "^ >> '& , ai 0) CQ^ _M -g cS S3 "g 02 s 1 .£: § *p ai ^ "ca I like Difl 'erenlJ job iter istic con;uraition was ;uratiions, itors and 10ns, sug- jiene ors. into 3 ver, -sip' OS a] aou [Oil • elei^enth ; Stud o )4) HOUSE AND WIGDOR 381 0 sI ai * 3 -*^ c fi ca ca ca a ft Ci 0 to w^ g U bc a) K 0 CO -2 0 Oi -^ IB 03 tH Q § '-5 .2 " " -2 ^ a .a ^ oi ^ _£1 •^^ ^ I s *^ s ^> |-^ § ^ 3 ^ 0 3 1 0 03 bo Oi Oi 382 PERSONNEL PSYCHOLOGY •n a 03 Oi fi S o .2 .2 m II a o ll ^ a "S a • " tH 1^ t» CO 03 X> 3 K T3 « Oi 0^ Ia . « J 'I 2 §• a §> > bC 03 ^3 •-H Xi s cn o PH co" o Oi bO o3 Si 03 "ft fi i ca 1g aa "O 00 <D •4-H 383 HOUSE AND WIGDOR 03 CO fi '-5 £ V^ o 03 E C CQ o3 > 03 a -^ a CO '+:> o3 '•B X3 1. Bot and Ci ^VH job s ^02 £ g 1 S al .2 ° ' CO 02 a '3 ft § s2 S bo en fi Oi ' 0 ai TS -^ 3 g § II ^.2 w ^ I I .§ "3 ""a 0 £ +^ o 01 - ^ •3 I o ai ca ft o xi '43 g. t» ?3 c? •3 13 iii o i § § =^ § o '-3 ta 'S ~ Ci III 5 tH ft 5^ .9 -.H -a o « tt» t i tH •O 03 fi S P . _ <s a S" III > T3 fi o3 ce a ^' a) V a PJ I bO CQ ai Ts -2 C3 o3 384 PERSONNEL PSYCHOLOGY leadership, the suitability of supplies and equipment, the efficiency of scheduling and coordinating procedures, or the abilities of the members of the work force are found deficient, highly motivated behavior may have either little effect on productivity or even possibly the effect of causing frustration which interferes with productivity. Empiric Research Based on Critical-Incident Methodology In Work and the Nature of Man, Herzberg (1966) reports the results of 10 critical-incident studies on 17 different populations. He asserts that these studies support the dual-factor theory in 97% of the cases. Table 1 is taken from Herzberg's 1966 book and summarizes the results of these studies. Each X in the table represents a correct prediction for a factor, while a dash indicates an incorrect prediction. The blank spaces suggest no significant evidence either way because of (a) failure of an investigator to include the factor in the analysis, (b) the scoring of only major factors in the events, (c) the general rarity of a factor occurring, or (d) occasional moderate frequency of a factor to be associated with both satisfaction and dissatisfaction. The chart shows that theoretical predictions, when made for each separate study, were valid in 97 percent of the cases. However, compilation of the number of people mentioning one of Herzberg's ten factors as a satisfier or dissatisfier yields Table 2.' From this table it can be observed that achievement is seen by most respondents as more of a dissatisfier than Relations with supervisors or Working conditions. In fact. Achievement can be considered the third major dissatisfier. Recognition is also found to be more of a dissatisfier than both Working conditions and Relations with superiors. Using these data from Table 2, one can rank dissatisfiers as follows: ' This analysis is restricted to those factors mentioned more than four times. By restricting this analysis to those factors, several factors are excluded. The excluded factors are Opportunity for growth. Interpersonal relations with subordinates. Status, Personal life. Security and Salary. With the exception of Opportunity for growth, these excluded factors are peripheral to the TwoFactor theory, and their inclusion in this analysis would not change the major conclusion suggested by the analysis. HOUSE AND WIGDOR 385 Company policy and administration Supervision Achievement Recognition Working conditions Work itself Relations with superior Advancement Responsibility This ranking can be partially explained by considering the fact that every factor did not appear in every study reported by Herzberg. However, in all studies, each factor had an equal chance of occurring and did not because of failure of respondents to mention incidents relating to all factors. Evidence Based on Methods other than the Critical-Incident Method Since the publication of the original research by Herzberg, Mausner, and Snyderman in 1959, several studies based on different research methods have been reported in the literature. These studies are described in brief detail in Exhibit 1. Conclusions Our secondary analysis of the data presented by Herzberg (1966) in his most recent book yields conclusions contradictory to the proposition of the Two-Factor theory that satisfiers and dissatisfiers are unidimensional and independent. Although many of the intrinsic aspects of jobs are shown to be more frequently identified by respondents as satisfiers, achievement and recognition are also shown to be very frequently identified as dissatisfiers. In fact, achievement and recognition are more frequently identified as dissatisfiers than working conditions and relations with the superior. Since the data do not support the satisfier-dissatisfier dichotomy, the second proposition of the Two-Factor theory, that satisfiers have more motivational force than dissatisfiers, appears highly suspect. This is true for two reasons. First, any attempt to separate the two requires an arbitrary definition of the classifications satisfier and dissatisfier. Second, unless such 386 PERSONNEL PSYCHOLOGY an arbitrary separation is employed, the proposition is untestable. Turning to our review of previous studies based on methods other than the storytelling method (Exhibit 1), four important conclusions emerge concerning the operation of, and variables associated with, the various job characteristics pertinent to satisfaction or dissatisfaction. These four conclusions are: 1. A given factor can cause job satisfaction for one person and job dissatisfaction for another person, and vice versa. Job satisfaction is a function of the perceived characteristics of a job in relation to an individual frame of reference. A particular job condition on the basis of this theoretical, can be a satisfier, dissatisfier or irrelevant depending on conditions in comparable jobs, conditions of other people, of the qualifications and past experience of the individual as well as on numerous situational variables of the present job. Thus, job satisfaction is not an absolute phenomena but is relative to the alternatives available to the individual. (Smith & Kendall, 1963, p. 14.) Variables that partially determine whether a given factor will be a source of satisfaction or dissatisfaction on the job were shown to be: Job or occupational level: Centers and Bugental (1966), Myers (1964), Rosen (1963), Friedlander (1966b), Dunnette (1965). Age of respondents: Singh and Baumgartel (1966), Saleh (1964), Friedlander (1966b), Wernimont (1966). Sex of respondents: Centers and Bugental (1966), Gibson (1961), Myers (1964). Formal education: Singh and Baumgartel (1966). Culture: Turner and Lawrence (1965), Ott (1965). Time-dimension variable: Ewen (1964), Wernimont (1966). Respondent's standing in his group: Eran (1966). 2. A given factor can cause job satisfaction and dissatisfaction in the same sample (Dunnette, 1965; Ewen, 1964; Gordon, 1965; Burke, 1966; Ewen, Smith, Hulin & Locke, 1966; Friedlander, 1963; Wernimont, 1966; Halpern, 1966; Ott, 1965; Hinrichs & Mischkind, 1967; Graen, 1966; Malinovsky & Barry, 1965). 3. Intrinsic job factors are more important to both satisfy- HOUSE AND WIGDOR 387 ing and dissatisfying job events (Dunnette et al., 1967; Wernimont, 1966; Ewen, Smith, Hulin & Locke, 1966; Graen, 1966; Friodlander, 1964). 4. These conclusions lead us to agree with the criticism advanced by Dunnette, Campbell and Hakel (1967) that the Two-Factor theory is an oversimplification of the relationships between motivation and satisfaction, and the sources of job satisfaction and dissatisfaction. References BRAYFIBLD, A . H . AND CROCKETT, W . H . "Employee Attitudes and Employee Performance." Psychological Bulletin, LII (1955), 396-424. BDBKE, R . "Are Herzberg's Motivators and Hygienes Unidimensional?" Journal of Applied Psychology, L (1966), 317-321. CENTEBS, R . AND BUGBNTAL, D . E . "Intrinsic and Extrinsic Job Motivations among Different Segments of the Working Population." Journal of Applied Psychology, L (1966), 193-197. DUNNETTE, M . D . "Factor Structure of Unusually Satisfying and Unusually Dissatisfying Job Situations for Six Occupational Groups." Paper read at Midwestern Psychological Association. Chicago, April 29-May 1, 1965. DUNNETTE, M . D . , CAMPBELL, J. P., AND HAKEL, M . D . "Factors Contributing to Job Satisfaction and Job Dissatisfaction in Six Occupational Groups." Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, II (1967), 143-174. EEAN, M . "Relationship Between Self-Perceived Personality Traits and Job Attitudes in Middle Management." Journal of Applied Psychology, XLIX (1966), 424-430. EWEN, R . B . "Some Determinants of Job Satisfaction: A Study of the Generality of Herzberg's Theory." Journal of Applied Psychology, XLVIII (1964), 161-163. EWEN, R . B . , SMITH, P. C , HULIN, C . L . , AND LOCKE, E . A. "An Empirical Test of the Herzberg Two-Factor Theory." Joumal of Applied Psychology, L (1966), 544-550. FANTZ, R . "Motivational Factors in Rehabilitation." Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. Western Reserve University, 1962. FINE, S. AND DICKMAN, R . "Satisfaction and Productivity." Paper presented at the American Psychological Association Convention, St. Louis, Missouri, September, 1962. FouHNET, G. P., DisTEFANO, M. K., J B . , AND PBTEB, M . "Job Satisfaction: Issues and Problems." Personnel Psychology, XIX (1966), 165-183. PBIEDLANDEB, F . "Underlying Sources of Job Satisfaction." Journal of Applied Psychology, XLVII (1963), 246-250. FBIEDLANDEB, F . "Job Characteristics as Satisfiers and Dissatisfiers." Journal of Applied Psychology, XLVIII (1964), 38&-392. FBIEDLANDEB, F . "Motivation to Work and Organizational Performance." Journal of Applied Psychology, L (1966), 143-152. (a) FBIEDLANDEB, F . "Importance of Work Versus Nonwork among Socially and Occupationally Stratified Groups." Journal of Applied Psychology, L (1966), 437-441. (b) 388 PERSONNEL PSYCHOLOGY FBIEDLANDEB, F . AND WALTON, E . "Positive and Negative Motivations toward Work." Administrative Science Quarterly, IX (1964), 194-207. GIBSON, J. W. "Sources of Job Satisfaction and Job Dissatisfaction as Interpreted from Analysis of Write-in Responses." Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. Western Reserve University, 1961. GORDON, G. G. "The Relationship of Satisfiers and Dissatisfiers to Productivity, Turnover, and Morale." Paper presented at the American Psychological Association Convention, Chicago, Illinois, September 1965. GBAEN, G. "Motivator and Hygiene Dimensions for Research and Development Engineers." Journal of Applied Psychology, L (1966), 563-566. GRAGLIA, A . AND HAMLIN, R . "Effect of Effort and Task Orientation on Activity Preference." Paper presented at Eastern Psychological Association Meeting, Philadelphia, 1964. HAHN, C . "Dimensions of Job Satisfaction and Career Motivation." Unpublished manuscript, 1959. HALPBRN, G . "Relative Contributions of Motivator and Hygiene Factors to Overall Job Satisfaction." Journal of Applied Psychology, L (1966), 198200. HAMLIN, R . M . AND NEMO, R . S. "Self-Actualization in Choice Scores of Improved Schizophrenics." Journal of Clinical Psychology, XVIII (1962), 51-54. HAYWOOD, H . C . AND DOBBS, V. "Motivation and Anxiety in High School Boys." Journal of Personality, XXXII (1964), 371-379. HEBZBEBG, F . Work and the Nature of Man. Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1966. HBBZBEBG, F . , MAUSNEB, B . , PETERSON, R . , AND CAPWELL, D . F . Job Atti- tudes: Review of Research and Opinion. Pittsburgh: Psychological Services of Pittsburgh, 1957. HEBZBERG, F . , MAUSNEK, B . , AND SNYDEBMAN, B . The Motivation to Work (Second Edition). New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1959. HINRICHS, J. R. AND MISCHKIND, L . A. "Empirical and Theoretical Limitations of the Two-Factor Hypothesis of Job Satisfaction." Journal of Applied Psychology, LI (1967), 191-200. KuHLEN, R. G. "Needs, Perceived Need Satisfaction Opportunities, and Satisfaction with Occupation." Journal of Applied Psychology, XLVII (1963), 56-64. MALINOVSKY, M . R . AND BABBY, J. R. "Determinants of Work Attitude." Journal of Applied Psychology, XLIX (1965), 446^51. M Y E B S , M . S. "Who Are Your Motivated Workers?" Harvard Business Review, XLII (1964), 73-88. OTT, D . C . "The Generality of Herzberg's Two-Factor Theory of Motivation." Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. The Ohio State University, 1965. PoBTEB, L. W. "Job Attitudes in Management: I. Perceived Deficiencies in Need J^ulfiUment as a Function of Job Level." Journal of Applied Psychology, XLVI (1962), 375-384. ROSEN, H . "Occupational Motivation of Research and Development Personnel." Personnel Administration, XXVI (1963), 37-43. SALEH, S . "A Study of Attitude Change in the Pre-Retirement Period." Journal of Applied Psychology, XLVIII (1964), 310-312. SANDVOLD, K . "The Effect of Effort and Task Orientation on the Motivator HOUSE AND WIODOR 389 Orientation and Verbal Responsivity of Chronic Schizophrenic Patients and Normals." Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. University of Illinois, 1962. ScHWABz, p . Attitudes of Middle Management Personnel. Pittsburgh: American Institute for Research, 1959. SINGH, T . M . AND BAUMGARTEL, H . "Background Factors in Airline Mechanics' Work Motivations." Journal of AppUed Psychology, L (1966), 337-339. SMITH, P. C. AND KENDALL, L . M . "Cornell Studies of Job Satisfaction." Unpublished manuscript, 1963. TURNER, A. N. AND LAWRENCE, P. R. Industrial Jobs and the Worker. Cam- bridge: Harvard University Graduate School of Business Administration, 1965. VROOM, V. H. Work and Motivation. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1964. VHOOM, V. H. "Some Observations Regarding Herzberg's Two-Factor Theory." Paper presented at the American Psychological Association Convention, New York, September, 1966. WERNIMONT, P. F. "Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors in Job Satisfaction." Journal of Applied Psychology, L (1966), 41-50. YADOV, V. A. "The Soviet and American Worker: Job Attitudes." Soviet Life January, 1965.