Common techniques for quantitative seismic interpretation

advertisement

I

techniques

forquantitative

4 Common

seismic

interpretation

-

Thereare no facts,only interpretations.

lriedrith

Niet:sche

-

4.1 Introduction

Conventionalseismicinterpretationimplies picking and tracking laterally consistent

seismic reflectors for the purpose of mapping geologic structures,stratigraphy and

reservoirarchitecture.

The ultimategoal is to detecthydrocarbonaccumulations,

delineatetheir extent, and calculatetheir volumes.Conventionalseismic interpretationis an

art that requires skill and thorough experiencein geology and geophysics.

Traditionally, seismicinterpretationhasbeenessentiallyqualitative.The geometrical

expressionof seismic reflectorsis thoroughly mapped in spaceand traveltime,but litfle

emphasisis put on the physicalunderstandingof seismicamplitudevariations.In the

last few decades,however, seismic interpretershave put increasingemphasison more

quantitative techniques fbr seismic interpretation,as these can validate hydrocarbon

anomalies and give additional information during prospect evaluation and reservoir

characterization.The most important of thesetechniquesinclude post-stackamplitucle

analysis(bright-spotanddim-spotanalysis),offset-dependent

amplitudeanalysis(AVO

analysis),acousticand elasticimpedanceinversion,and forward seismicmodeling.

These techniques,if used properly, open up new doors for the seismic interpreter.

The seismicamplitudes,representingprimarily contrastsin elasticpropertiesbetween

individual layers,contain information about lithology, porosity,pore-fluid type and saturation, as well as pore pressure- information that cannot be gained fiom conventional

s e i s m i ci n t e r p r e t a l i o n .

-

4.2 Qualitativeseismicamplitude

interpretation

Until a few decades ago, it would be common for seismic interpreters to roll out

l h e i r s e v e r a l - m e t e r s - l opnagp e rs e c t i o n swith seismic data down the hallway, go down

168

169

-

interpretation

4,2 Qualitative

seismicamplitude

on their knees,and use their colored pencils to interpretthe horizons of interestrn

order to map geologic bodies. Little attention was paid to amplitude variations and

their interpretations.In the early 1970sthe so-called"brighrspot" techniqueproved

successfulin areasof the Gulf of Mexico, wherebright amplitudeswould coincidewith

gas-filled sands.However, experiencewould show that this technique did not always

work. Some of the bright spots that were interpreted as gas sands,and subsequently

drilled, were fbund to be volcanic intrusions or other lithologies with high impedance

contrast compared with embedding shales.These tailures were also related to lack of

waveletphaseanalysis,ashardvolcanicintrusionswould causeoppositepolarityto lowimpedance gas sands.Moreover, experienceshowed that gas-filled sands sometimes

could cause"dim spots," not "bright spots," if the sandshad high impedancecompared

with surroundingshales.

With the introductionof 3D seismicdata, the utilization of amplitudesin seismic

interpretation became much more important. Brown (see Brown et ul., l98l) was

one of the pioneersin 3D seismicinterpretationof lithofaciesfiom amplitudes.The

generationoftime slicesand horizon slicesrevealed3D geologic patternsthat had been

impossible to discover from geometric interpretationof the wiggle tracesin 2D stack

sections.Today, the further advance in seismic technology has provided us with 3D

visualizationtools where the interpretercan stepinto a virtual-realityworld of seismic

wiggles and amplitudes, and trace these spatially (3D) and temporally (4D) in a way

that one could only dream of a few decadesago. Certainly, the leap fiom the rolled-out

paper sectionsdown the hallways to the virtual-reality imagesin visualization "caves"

is a giant leap with greatbusinessimplicationsfor the oil industry.In this sectionwe

review the qualitative aspectsof seismicamplitude interpretation,before we dig into the

techniquessuchasAVO analysis,impedance

more quantitativeand rock-physics-based

inversion,and seismicmodeling,in fbllowing sections.

phaseandpolarity

4.2.1 Wavelet

The very first issue to resolve when interpreting seismic amplitudes is what kind of

wavelct we have. Essentialquestionsto ask are the fbllowing. What is the defined

I

polarity in our case?Are we dealingwith a zero-phaseor a minimum-phasewavelet?

Is there a phase shift in the data? These are not straightfbrward questions to answet,

becausethe phase of the wavelet can change both laterally and vertically. However,

there are a f'ew pitfalls to be avoided.

First, we want to make sure what the defined standardis when processingthe data.

There exist two standards.The American standarddefinesa black peak as a "hard" or

"positive" event,and a white trough as a "soft" or a "negative"event.On a near-ofl.set

stack section a "hard" event will correspondto an increasein acousticimpedancewith

depth, whereasa "soft" event will correspondto a decreasein acousticimpedancewith

depth. According to the European standard,a black peak is a "soft" event, whereas a

170

T

Gommon

techniques

for quantitative

seismicinterpretation

white trough is a "hard" event. One way to check the polarity of marine data is to look

at the sea-floorreflector.This reflector should be a strongpositive reflector representing

the boundary between water and sediment.

Datapolarity

' American polarity: An increasein impedancegives positiveamplitude.

normally

displayedas black peak (wiggle r.race)or red intensitylcolor displayt.

. European(or Australian)polarity:An increasein impedancegives

negal.ive

amplitude, normally displayedas white rrough (wiggle trace) or blue intensity(color

display).

(Adaptedfrom Brown. 200la, 2001b)

For optimal quantitative seismic interpretations,we should ensurethat our data are

zero-phase.Then, the seismicpick should be on the crest of the waveform conesponding with the peak amplitudes that we desire for quanrirativeuse (Brown, l99g). with

today's advanced seismic interpretation tools involving the use of interactive workstations,there exist various techniquesfbr horizon picking that allow efficient interpretationof large amountsof seismicdata.Thesetechniquesinclude manualpicking,

interpolation,autotracking,voxel tracking, and surfaceslicing (see Dorn (199g) fbr

detaileddescriptions).

For extraction of seismic horizon slices, autopicked or voxel-tracked horizons are

very common. The obvious advantageof autotracking is the speed and efficiency.

Furthermore, autopicking ensuresthat the peak amplitude is picked along a horizon.

However,one pitfall is the assumptionthat seismichorizons are locally continuous

and consistent.A lateral change in polarity within an event will not be recognized

during autotracking.Also, in areasof poor signal-to-noiseratio or where a single event

splits into a doublet, the autopicking may fail to track the corect horizon. Not only

will important reservoirparametersbe neglected,but the geometriesand volumes may

also be significantly off if we do not regard lateral phaseshifts. It is important that the

interpreterrealizesthis and reviewsthe seismicpicks for quality control.

4.2.2 Sand/shale

cross-overs

with depth

Simple rock physicsmodeling can assistthe initial phaseof qualitativeseismicinrerpretation, when we are uncertain about what polarity to expect for diff'erentlithology

boundaries.

In a siliciclasticenvironment,most seismicreflectorswill be associated

with

sand-shaleboundaries.Hence, the polarity will be related to the contrastin impedance

between sand and shale.This contrastwill vary with depth (Chapter 2). Usually, relatively sott sandsare fbund at relatively shallow depths where the sandsare unconsolidated. At greater depths, the sandsbecome consolidatedand cemented.whereas the

171

-

4.2 Qualitative

seismicamplitude

interpretati0n

Sandversus

shaleimpedance

depthtrends

polarity

(schematic)

andseismic

rmpe0ance

1

t

Sand-shale

cross-over

DeDth

Figure4'1 Schematic

depthtrendsof sandandshaleimpeclances.

Thedepthtrendscanvaryfiom

basinto basin,andtherecanbe morethanonecross-over.

Localdepthtrendsshouldbeestablished

for differentbasins.

shalesare mainly affectedby mechanicalcompaction.Hence, cementedsandstonesare

normally found to be relatively hard eventson the seismic.There will be a corresponding cross-overin acousticimpedanceof sandsand shalesas we go fiom shallow and soft

sandsto the deep and hard sandstones(seeFigure 4.1). However, the depth trends can

be much more complex than shown in Figure 4.1 (Chapter2, seeFigures 2.34 and,2.35').

Shallow sandscan be relatively hard comparedwith surroundingshales,whereasdeep

cementedsandstonescan be relatively soft compared with surounding shales.There

is no rule of thumb fbr what polarity to expect fbr sandsand shales.However, using

rock physics modeling constrainedby local geologic knowledge, one can improve the

understandingof expectedpolarity of seismic reflectors.

"Hard"venius"soft"events

During seismicinterpretationof a prospector a provenreser"yoir

sand.the following

questionshould be one of the first to be asked:what type of event do we expect,

a "hard" or a "soft"? [n other words. should we pick a positivepeak, or a negative

trough?lfwe havegood well control,this issuecan be solvedby generatingsynthetic

seismograms

and correlatingthesewith realseismicdata.If we haveno well control,

we may have to guess. However. a reasonableguess can be made based on rock

physics modeling. Below we have listed some "rules of thumb" on what type of

reflector we expect l-ordifferent geologic scenarios.

172

Common

techniques

for quantitative

seismicinterpretation

T

Typical

"hard"events

. Very shallow sandsat normal pressureembeddedin pelagicshales

. Cementedsandstonewith brine saluration

. Carbonaterocks embeddedin siliciclastics

' M i x e c ll i t h o l o g i e s( h e t e r o l i t h i c sl i)k e s h a t ys a n d s m

, a r l s .v o l c a n i ca s hd e p o s i t s

Typical"soft" events

. Pelagic

shale

' S.hallow,unconsolidated

sands(any pore fluid) embeddedin normally compacted

shales

' Hydrocarbonaccumularionsin clean.unconsolidated

or poorly consolidatedsancls

. Overpressured

zones

Somepitfallsin conventional

interpretation

' Make sure you know the polarity of the data. Rememberthere are two

different

standards,the US standardand the Europeanstandard.which are opposire.

' A hard event can changeto a soft laterally (i.e.. lateralphaseshifi;

if there are

petrographicor pore-fluidchanges.Seismicaurotrackingwill nor derecr

l:jloloCic.

these.

' A d i m s e i s m i cr e f l e c t o ro r i n t e r v a lm a y b e s i g n i f i c a n te. s p e c i a l l yi n

t h e z o n eo f

sand/shaleimpedancecross-over.AVO analysisshould be underrakento reveal

potentialhydrocarbonaccumulations.

I

ii

ji

4.2.3 Frequency

andscaleeffects

Seismic resolution

Verticalseismicresolutionis definedas theminimum separationbetweentwo interfaces

such that we can identify two interfacesrather than one (SherifTand Geldhart, 199-5).

A stratigraphiclayer can be resolvedin seismicdataif the layer thicknessis largerthan

a quarter of a wavelength.The wavelength is given by:

\

-

t/ /f

(4.1)

where v is the interval velocity of the layer, and.l is the frequency of the seismic wave. lf the wavelet has a peak frequency of 30 Hz, and the layer velocity is

3000 m/s, then the dominant wavelengthis 100 m. In this case,a layer of 25 m can

be resolved.Below this thickness,we can still gain important infbrmation via quantitative analysisof the interferenceamplitude.A bed only ),/30 in thicknessmay be

detectable,althoughits thicknesscannotbe determinedfiom the wave shape(Sheriff and

Geldhart.199-5).

173

E

interpretation

seismicamplitude

4.2 Qualitative

tiickness

Layer

fbr a givenwavelength.

of layerthickness

asa function

amplitude

4,2 Seismic

Figure

The horizontal resolution of unmigrated seismic data can be defined by the Fresnel

zone. Approximately, the Fresnel zone is defined by a circle of radius, R, around a

r e l l e c t i o np o i n t :

n - Jgz

G.2)

where z is the reflector clepth.Roughly, the Fresnel zone is the zone from which all

reflected contributions have a phase difl-erenceof less than z radians. For a depth of

3 km and velocity of 3 km/s, the Fresnelzone radius will be 300-470 m for fiequencies

ranging fiom 50 to 20 Hz. When the size of the reflector is somewhat smaller than

the Fresnel zone, the responseis essentiallythat of a diffraction point. Using prestack migration we can collapse the difliactions to be smaller than the Fresnel zone,

thus increasingthe lateralseismicresolution(Sheriff and Geldhart,1995).Depending

on the migration aperture, the lateral resolution after migration is of the order of a

wavelength.However,the migration only collapsesthe Fresnelzone in the direction

of the migration, so if it is only performed along inlines of a 3D survey, the lateral

resolution will still be limitecl by the Fresnelzone in the cross-linedirection. The

lateral resolution is also restricted by the lateral sampling which is governed by the

spacing between individual CDP gathers,usually 12.5 or 18 meters in 3D seismic

clata.For typical surf'aceseismic wavelengths(-50-100 m), lateral sampling is not the

l i m i t i n gl a c t o r .

Interference and tuning effects

A thin-layered reservoir can cause what is called event tuning, which is interf'erence

betweenthe seismicpulse representingthe top of the reservoirand the seismicpulse

representingthe baseof the reservoir.This happensif the layer thicknessis less than a

quarterof a wavelength(Widess,1973).Figure 4.2 showsthe efTectiveseismicamplitude as a function of layer thickness for a given wavelength, where a given layer

has higher impedancethan the surrounding sediments.We observethat the amplitude

174

-

Gommon

techniques

for quantitative

seismicinterpretation

increasesand becomes larger than the real reflectivity when the layer thickness is

between a half and a quarter of a wavelength. This is when we have constructive

interference between the top and the base of the layer. The rlaximum constructive

interferenceoccurs when the bed thickness is equal to ),14, and this is often referred

to as the tuning thickness.Furthermore, we observethat the amplitucledecreasesand

approacheszero for layer thicknessesbetween one-quarterof a wavelength and zero

thickness. We refer to this as destructive interferencebetween the top and the base.

Trough-to-peaktime measurements

give approximatelythe correctgrossthicknesses

for thicknesseslarger than a quarterof a wavelength,but no information fbr thicknesses

lessthan a quarterof a wavelength.The thicknessof an individualthin-bedunit can be

extractedfrom amplitude measurementsif the unit is thinner than about ),/4 (Sheriff

and Geldhart,1995).When the layer thicknessequals)./8, Widess(1973) found that

the composite responseapproximatedthe derivative of the original signal. He referred

to this thickness as the theoretical threshold of resolution. The amplitude-thickness

curve is almost linear below ),/8 with decreasingamplitudeas the layer gets thinner,

but the compositeresponsestaysthe same.

4.2.4 Amplitude

andreflectivity

strength

"Bright spots" and "dim spots"

The first use of amplitude information as hydrocarbon indicators was in the early

1970swhen it was fbund that bright-spotamplitude anomaliescould be associated

with hydrocarbon traps (Hammond, 1974). This discovery increased interest in the

physical propertiesof rocks and how amplitudeschangedwith difTerenttypes of rocks

and pore fluids (Gardner et al., 1914').In a relatively soft sand, the presenceof gas

and/or light oil will increasethe compressibilityof the rock dramatically,the velocity will drop accordingly,and the amplitudewill decreaseto a negative"bright spot."

However, if the sand is relatively hard (compared with cap-rock), the sand saturated

with brine may induce a "brighlspot" anomaly,while a gas-filledsandmay be transparent, causing a so-calleddim spot, that is, a very weak reflector.It is very important

before startingto interpret seismicdata to find out what changein amplitude we expect

for different pore fluids, and whether hydrocarbonswill cause a relative dimrning or

brighteningcomparedwith brine saturation.Brown (1999)statesthat "the most impnrtant seismic property of a reservoir is whether it is bright spot regime or tlim sltot

regime."

One obvious problem in the identification of dim spotsis that they are clim - they are

hard to see.This issuecan be dealt with by investigatinglimited-rangestack sections.

A very weak near-offsetreflector may have a correspondingstrong f'ar-oflsetreflector.

However,some sands,although they are significant,produce a weak positive nearoffset reflection as well as a weak negative far-offset reflection. Only a quantitative

analysisof the changein near-to far-offsetamplitude,a gradientanalysis,will be able

175

T

interpretation

seismicamplitude

4.2 Qualitative

to reveal the sand with any considerabledegree of confidence. This is explained in

Section4.3.

Pitfalls:False"bright spots"

During seismicexplorationof hydrocarbons."brighr spots"are usuallythe first type

of DHI (direct hydrocarbonindicators)one looks for. However.there have been

severalcaseswhere bright-spotanomalieshavebeendrilled. and turned out not lo

be hydrocarbons.

Some common "false bright spors"include:

. Volcanicintrusionsand volcanicash layers

. Highly cementedsands.often calcitecementin thin pinch-outzones

. Low-porosityheterolithicsands

. Overpressured

sandsor shales

. Coal beds

. Top of salt diapirs

Only the last threeon the list abovewill causethe samepolarity as a gas sand.The

first three will causeso-called"hard-kick" amplitudes.Therefore.if one knows the

bright

polariryof the dataone shouldbe able lo discriminarehydrocarbon-associated

"hard-kick"

permit

discrimination

should

AVO

analysis

anomalies.

spots from the

sands/shales.

of hydrocarbonsfrom coal, salt or overpressured

among seismicinterpretersis

used

attribute

A very common seismicamplitude

amplitudescalculatedover a given

rellectionintensity,which is root-mean-square

lime window. This anribute does not distinguish between negativeand positive

amplitudes;thereforegeologic interpretationol this attributeshould be made with

greatcaution.

"Flat spots"

Flat spotsoccur at the reflectiveboundary betweendifferent fluids, either gas-oil, gaswarer,or warer-oil contacts.Thesecan be easyto detectin areaswhere the background

stratigraphyis tilted, so the flat spot will stick out. However, if the stratigraphyis more

or less flat, the fluid-related flat spot can be difficult to discover. Then, quantitative

methods like AVO analysiscan help to discriminate the fluid-related flat spot from the

fl arlying lithostratigraphy.

One should be aware of severalpitfalls when using flat spots as hydrocarbon indicators. Flat spots can be related to diagenetic events that are depth-dependent.The

boundary between opal-A and opal-CT representsan impedance increasein the same

way as fbr a fluid contact, and dry wells have been drilled on diagenetic flat spots.

Clinoforms can appear as flat features even if the larger-scalestratigraphy is tilted.

sheet-flooddepositsand

Other "false" flat spotsinclude volcanicsills, paleo-contacts,

flat basesof lobesand channels.

tl

176

-

for quantitative

Common

techniques

seismicinterpretation

Pitfalls:

False

"flatspots"

One of f he best DHIs ro look for is a flat spot, the contactbetweengas and water,

gas and oil, or oil and water.However.there are other causesthat can give rise to

flat spots:

. Oceanbottom multiples

. Flat stratigraphy.The basesof sand lobesespeciallytend to be flat.

. Opal-A to opal-CT diageneticboundary

. Paleo-contacts,

either relatedto diagenesisor residualhydrocarbonsaturation

. Volcanicsills

Rigorousflat-spotanalysisshould include detailedrock physicsanalysis.and forward seismicmodeling,as well as AVO analysisof real data(seeSection4.3.8).

Lithology, porosity and fluid ambiguities

The ultimategoal in seismicexplorationis to discoverand delineatehydrocarbonreservoirs. Seismic amplitude maps from 3D seismicdata are often qualitarlvel.finterpreted

t

I

lt

il

i,

in termsof lithology and fluids.However,rigorousrock physicsmodelingand analysis

of available well-log data is required to discriminate fluid effects quantitatively trom

lithology effects (Chapters I and 2).

The "bright-spot" analysismethod has ofien been unsuccessfulbecauselithology

effects rather than fluid eff-ectsset up the bright spot. The consequenceis the drilling of

dry holes.In order to reveal"pitfall" amplitude anomaliesit is essentialto investigatethe

rock physicspropertiesfiom well-log data.However,in new frontier areaswell-1ogdata

are sparseor lacking. This requiresrock physicsmodeling constrainedby reasonable

geologic assumptionsand/or knowledge about local compactionaland depositional

trends.

A common way to extractporosity from seismicdata is to do acousticimpedance

inversion.Increasingporositycan imply reducedacousticimpedance,and by extracting empiricalporosity-impedance

trendsfrom well-log data,one can estimateporosity

from the inverted impedance.However, this methodology suffers from several ambiguities. Firstly, a clay-rich shalecan have very high porosities,even if the permeability

is closeto zero.Hence,a high-porosityzone identifiedby this techniquemay be shale.

Moreover, the porosity may be constant while fluid saturationvaries, and one sin-rple

impedance-porositymodel may not be adequatefbr seismicporositymapping.

In addition to lithology-fluid ambiguities, lithology-porosity ambiguities, and

porosity-fluid ambiguities,we may have lithology-lithology ambiguitiesand fluidfluid ambiguities.Sand and shalecan have the sameacousticimpedance,causingno

reflectivity on a near-offset seismic section. This has been reported in several areas

of the world (e.g. Zeng et al., 1996 Avseth et al., 2001b). It is often reported that

fluvial channelsor turbidite channelsare dim on seismic amplitude maps, and the

Plate1,1 SeismicP-P amplitudemap over a submarinefan. The amplitudesare sensitiveto lithofaciesand

pore fluids, but the relationvariesacrossthe imagebecauseofthe interplayofsedimentologicand diagenetic

influences.Blue indicateslow amplitudes,yellow and red high amplitudes.

4120

4140

2.92

4160

2.94

41B0

5

o

4200

E

o

o

2.96

F

4220

2.98

4240

3

4260

4280

3.02

4300

rn0

VP

rho*l/p

lilllWi7",

:fff!;"{riii;iiiffr

2.9

,)))))))t)))l)))))))))f

))

t) )) D,D

) )), ) D,D

D)) Dr r,D)r>),

),l?? )?i)i)p

i)P,?),,?l?

iriiiiiiii

iiiiir)ii)i)

ii

lrlllliilrlllllil,

10

15

Distance

20

25

Plate1,30 Top left, logs penetratinga sandyturbidite sequence;top right, normal-incidencesyntheticswith a

50 Hz Ricker wavelet.Bottom: increasingwater saturationS* from l1a/cLo907c(oil API 35, GOR 200)

increasesdensityand Vp (left), giving both amplitudeand traveltimechanges(right).

177

r

interpretation

4.2 Qualitative

seismicamplitude

interpretation is usually that the channel is shale-filled. However, a clean sand filling in the channel can be transparentas well. A geological assessmentof geometries

indicating differential compaction above the channel may reveal the presenceof sand.

More advancedgeophysical techniquessuch as offset-dependentreflectivity analysis

may also reveal the sands.During conventionalinterpretation,one should interpret top

reservoir horizons from limited-range stack sections,avoiding the pitfall of missing a

dim sandon a near-or full-stackseismicsection.

Facies interpretation

Lithology influence on amplitudes can often be recognized by the pattern of amplitudes as observed on horizon slices and by understandinghow different lithologies

occur within a depositionalsystem.By relatinglithologiesto depositionalsystemswe

often refer to theseas lithofacies or f-acies.The link between amplitude characteristics

and depositional patternsmakes it easierto distinguish lithofacies variations and fluid

changesin amplitudemaps.

Traditional seismicfaciesinterpretationhasbeenpredominantlyqualitative,basedon

seismictraveltimes.The traditionalmethodologyconsistedof purely visual inspection

of geometricpatternsin the seismicreflections(e.g.,Mitchum et al., 1977;Weimer and

Link, l99l ). Brown et al. (1981),by recognizingburiedriver channelsfrom amplitude

information, were amongst the first to interpret depositional facies from 3D seismic

amplitudes.More recent and increasinglyquantitativework includesthat of Ryseth

et al. (.1998)who used acoustic impedance inversions to guide the interpretation of

sand channels, and Zeng et al. (1996) who used forward modeling to improve the

understandingof shallow marine facies from seismic amplitudes.Neri (1997) used

neuralnetworksto map faciesfrom seismicpulse shape.Reliablequantitativelithofacies

prediction fiom seismicamplitudesdependson establishinga link betweenrock physics

properties and sedimentaryfacies. Sections2.4 and 2.5 demonstratedhow such links

might be established.The case studies in Chapter 5 show how these links allow us to

predict litholacies from seismic amplitudes.

Stratigraphic interpretation

The subsurfaceis by nature a layered medium, where different lithologies or f'acies

have been superimposedduring geologic deposition. Seismic stratigraphicinterpretation seeksto map geologic stratigraphyfrom geometricexpressionof seismicreflections

in traveltime and space.Stratigraphic boundariescan be defined by dilferent lithologies (taciesboundaries)or by time (time boundaries).These often coincide,but not

always. Examples where facies boundaries and time boundaries do not coincide are

erosional surfacescutting across lithostratigraphy,or the prograding fiont of a delta

almost perpendicularto the lithologic surf'aceswithin the delta.

There are severalpittalls when interpretingstratigraphyfiom traveltime infbrmation.

First, the interpretationis basedon layer boundariesor interf'aces,that is, the contrasts

a

178

seismicinterpretation

for quantitative

techniques

Gommon

T

between diff'erent strata or layers, and not the properties of the layers themselves.

Two layers with different lithology can have the same seismic properties; hence, a

lithostratigraphic boundary may not be observed. Second' a seismic reflection may

occur without a lithology change(e.g.,Hardage,1985).For instance,a hiatuswith no

depositionwithin a shaleintervalcan give a strongseismicsignaturebecausethe shales

above and below the hiatus have difTerent characteristics.Similarily, amalgamated

sandscan yield internal stratigraphywithin sandy intervals,reflecting different texture

of sanclsfiom difl-erentdepositionalevents.Third, seismicresolution can be a pitfall in

seismicinterpretation,especiallywhen interpretingstratigraphiconlapsor downlaps.

Theseareessentialcharacteristicsin seismicinterpretation,asthey can give information

about the coastal development related to relative sea level changes (e.g., Vail er ai.,

I 977). However, pseudo-onlapscan occur if the thicknessof individual layers reduces

beneaththe seismicresolution.The layer can still exist,even if the seismicexpression

yields an onlap.

Pittalls

that can

Thereareseveralpitfalls in conventionalseismicstratigraphicinterpretation

be avoidedif we usecomplementaryquantitativetechniques:

. lmportant lithostratigraphicboundariesbetweenlayerswith very weak contrasts

in seismicpropefiiescan easily be missed.However.if different lithologiesare

transparentin post-stackseismicdata.they arenormallyvisiblein pre-stackseismic

dara. AVO analysisis a useful tool to reveal sandswith impedancessimilar to

c a p p i n gs h a l e s{ s e eS e c t i o n4 . 3 1 .

. It is commonlybelievedthatseismiceventsaretime boundaries.andnot necessarily

lithostratigraphicboundaries.For instance.a hiatus within a shale may causea

strong seismicreflectionif the shaleabovethe hiatus is lesscompactedthan the

onc below.even if the lithology is the same.Rock physicsdiagnosticsof well-log

data may revealnonlithologicseismicevents(seeChapter2 ).

. Becauseof limited seismicresolution,false seismiconlapscan occur.The layer

may still existbeneathresolution.Impedanceinversioncan improvethe resolution.

and revealsubtle srrailgraphicfeaturesnot observedin the original seismicdata

( s e eS e c t i o n4 . 4 ) .

Quantitative interpretation of amplituclescan add information about stratigraphic

patterns,and help us avoid some of the pitfalls mentioned above.First, relating lithology to seismic properties(Chapter 2) can help us understandthe nature of reflections,

and improve the geologic understandingof the seismic stratigraphy.Gutierrez (2001)

showed how stratigraphy-guidedrock physics analysis of well-log data improved the

sequencestratigraphicinterpretationof a fluvial systemin Colombia using impedance

inversion of 3D seismicdata. Conducting impedanceinversion of the seismic data will

179

-

4,2 Qualitative

seismicamplitude

interpretation

give us layer propertiesfrom interfhceproperties,and an impedancecross-sectioncan

reveal stratigraphicfeaturesnot observedon the original seismic section. Impedance

inversion has the potential to guide the stratigraphicinterpretation,becauseit is less

oscillatorythan the original seismicdata,it is more readily correlatedto well-log data,

and it tends to averageout random noise, thereby improving the detectability of laterimpedance

ally weakreflections(Gluck et a\.,1997).Moreover,frequency-band-limited

inversioncan improve on the stratigraphicresolution,and the seismicinterpretationcan

be signilicantly modified if the inversionresultsare included in the interpretationprocedure. For brief explanationsof different types of impedanceinversions,seeSection4.4.

Forward seismicmodeling is also an excellenttool to study the seismicsignaturesof

geologicstratigraphy(seeSection4.5).

Layer thickness and net-to-gross from seismic amplitude

As mentioned in the previous section, we can extract layer thickness from seismic

amplitudes.As depictedin Figure 4.2,the relationshipis only linear for thin layersin

pinch-out zonesor in sheet-likedeposits,so one shouldavoid correlatinglayer thickness

to seismic amplitudes in areaswhere the top and baseof sandsare resolvedas separate

reflectorsin the seismic data.

Meckel and Nath (.1911)found that, for sands embedded in shale, the amplitude

would depend on the net sand present,given that the thicknessof the entire sequence

is less than ).14. Brown (1996) extended this principle to include beds thicker than

the tuning thickness,assumingthat individual sand layers are below tuning and that

the entire interval of interbeddedsandshas a uniform layering. Brown introduced the

"composite amplitude" defined as the absolute value summation of the top reflection

amplitude and the base reflection amplitude of a reservoir interval. The summation of

the absolute values of the top and the baseemphasizesthe eff'ectof the reservoir and

reducesthe effect of the embedding material.

Zeng et al. (.1996)studiedthe influenceof reservoirthicknesson seismicsignaland

introduced what they referred to as effective reflection strength, applicable to layers

thinnerthan the tunins thickness:

o'. - 2 " - Z ' n . ,

Zrr

(4.3)

where Z. is the sandstoneimpedance,216is the averageshaleimpedanceand /z is the

layerthickness.A more commonway to extractlayerthicknessfrom seismicamplitudes

is by linear regressionof relative amplitude versus net sand thickness as observed at

wells that are available.A recentcasestudy showing the applicationto seismicreservoir

mappingwas providedby Hill and Halvatis(2001).

Vernik et al. (2002) demonstratedhow to estimate net-to-grossfiom P- and Simpedances fbr a turbidite system. From acoustic impedance (AI) versus shear

impedance (SI) cross-plots, the net-to-gross can be calculated with the fbllowing

fbrmulas:

r

180

Common

techniques

for quantitative

seismicinterpretation

E

I

NIG:

VrungdZ

Zrr.

AZ

(4 4)

where V."n,lis the oil-sand fraction given bv;

SI-bAI-ce

Kano

at-ao

(4.-5)

where b is the averageslope of the shaleslope(06) and oil-sandslope(b1),whereasae

a n d z 7 ti i r e t h e r e s p e c t i v ien t e r c e p t isn t h e A I - S I c r o s s - p l o r .

c a l c u l a t i o no f r e s e r v o i rt h i c k n e s sf r o m s e i s m i ca m p l i t u d es h o u l db e d o n e o n l y i n

areaswhere sandsare expectedto be thinner than the tuning thickness.that is a

quarterof a wavelength.and wherewell-log datashow evidenceof good correlation

belweennet sandlhicknessand relativeamplirude.

It can be difficult to discriminatelayer rhicknesschangesfrom lirhologyand fluid

changes.In relativelysoft sands,the impactof increasingporosityand hydrocarbon

saturationtendslo increasethe seismicamplitude,and thereforeworks in the same

"direction" to Iayerthickness.However.in relativelyhard sands.increasingporosity

and hydrocarbonsaturationLendto decreasethe relalive amplitude and therefore

work in the opposite"direction" to layer thickness.

ilouo

anatysis

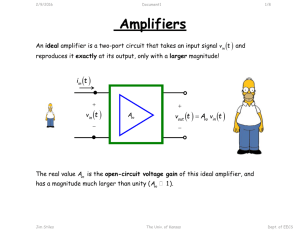

In 1984, 12 years afler the bright-spot technology became a commercial tool fbr

hydrocarbon prediction, ostrander published a break-through paper in Geophl-sics

(ostrander, 1984). He showed that the presenceof gas in a sand cappedby a

shale

would causean amplitude variation with ofTsetin pre-stackseismicdata.He also found

that this changewasrelatedto the reducedPoisson'sratio causedby the presenceofgas.

Then,the yearafter,Shuey(1985)confirmedmathematicallyvia approximationsof the

Zoeppritz equationsthat Poisson'sratio was the elasticconstantmost directly related

to the off.set-dependent

reflectivity fbr incident angles up to 30". AVo technology, a

commercial tool for the oil industry, was born.

The AVO techniquebecamevery popular in the oil industry,as one could physicaly

explainthe seismicamplitudesin termsof rock properties.Now, bright-spotanomalies

could be investigatedbeforestack,to seeif they also had AVo anomalies(Figure4.3).

The techniqueproved successfulin certain areasof the world, but in many casesit was

not successful.The technique sufI'eredfrom ambiguities causedby lithology efTects,

181

4.3 AVOanalysis

I

CDPgather

af interest

Stacksection

CDPgather

CDP

locqtion

Target harizon

. *{bu

Time

Geologic interpretation

AVO responseat

target horizon

Shale

0,1

-0

Sondstone

with gos

-0,

-0

Aryle ol inc,d?nca

Figure

4.3 Schematic

illustration

of theprinciples

in AVOanalysis.

tuning effects, and overburdeneft'ects.Even processingand acquisition effects could

causefalse AVO anomalies.But in many o1'thefailures,it was not the techniqueitself

that failed,but the useof the techniquethat was incorrect.Lack of shear-wavevelocity

informationandthe useof too simplegeologicmodelswerecommonreasonsfbr failure.

Processingtechniques that aff'ectednear-ofTsettraces in CDP gathers in a difl-erent

way from far-offset traces could also create talse AVO anomalies. Nevertheless,in

the last decade we have observed a revival of the AVO technique.This is due to the

improvementof 3D seismictechnology,betterpre-processing

routines,rnorefrequent

shear-wavelogging and improved understandingof rock physicsproperties,larger data

capacity,more fbcus on cross-disciplinaryaspectsof AVO, and last but not least,mclre

awarenessamong the usersof the potential pitfalls. The techniqueprovides the seismic

interpreter with more data, but also new physical dimensions that add infbrmation to

the conventional interpretationof seismic facies, stratigraphyand geomorphology.

In this section we describe the practical aspectsof AVO technology, the potential of this technique as a direct hydrocarbon indicator, and the pitfalls associated

with this technique. Without going into the theoretical details of wave theory, we

addressissuesrelatedto acquisition.processingand interpretationof AVO data. For

an excellent overview of the history of AVO and the theory behind this technology,

we refer the reader to Castagna(1993). We expect the luture application of AVO to

182

-

for quantitative

seismicinterpretation

Common

techniques

expandon today's common AVO cross-plotanalysisand hencewe include overviewsof

important contributions from the literature,include tuning, attenuationand anisotropy

effectson AVO. Finally, we elaborateon probabilistic AVO analysisconstrainedby rock

physicsmodels.Thesecomprisethe methodologiesappliedin casestudiesl, 3 and 4 in

Chapter5.

4.3.1 Thereflectioncoefficient

Analysis of AVO, or amplitude variation with ofTset,seeksto extract rock parameters

by analyzing seismic amplitude as a function of offset, or more corectly as a function

of reflection angle. The reflection coefficient for plane elastic waves as a lunction of

reflectionangle at a single interfaceis describedby the complicatedZoeppritz equations

(Zoeppritz,l9l9). For analysisof P-wavereflections,a well-known approximationis

given by Aki and Richards( 1980),assumingweak layer contrasts:

R ( 0 ,- )

I

, , Ap

- -1 7

,-vi ) +

;(r

2 *r4

T

AYp

W

,AVs

+ p' lt

K

(4.6)

where:

s i n0 1

I t - -

e:(0rlu)12=et

YPI

Lp:pz-pr

LVp:Vpz-Vpt

AVs-Vs:-Vsr

P : ( . P z I Pr)

l2

Vp : (.Vpz+ vPt)12

V5 : (V52+ vst)12

In the fbrmulasabove,p is the ray parameter,01 is the angleof incidence,and 02 is

the transmissionangle; Vp1and Vp2arethe P-wave velocities above and below a given

interface,respectively.Similarly, V51and V5r are the S-wavevelocities,while py and

p2 are densitiesabove and below this interface (Figure 4.4).

The approximation given by Aki and Richards can be further approximated(Shuey,

r9 8 5 ) :

R(01 ;:, R(o) + G sin29+ F(tan2e - sin2o;

where

R(o):;(T.T)

G::^+-'#(+.'+)

-+(:.'#)#+

:R(o)

(4.1)

183

n

4.3 AVOanalvsis

Medium1

(Vp1,V51,p1)

Medium

2

(Vn, Vsz,

Pi

PP(r)

PS{t)

Figure4'4 Reflectionsand transmissionsat a singleinterfacebetweentwo elastichalf-space

rr-redia

firr an incidentplaneP-wave.PP(i). There will be both a reflectedp-wave,pp(r). and

a transmittecl

P-wave,PP(t).Note that thereare wave mocleconversionsat the reflectionpoint occurrrng

ar

nonzeroincidenceangles.In additionto the P-waves,a reflectedS-wave,pS(r), and a

transrnitted

S-wave,PS(t),will be prodr.rced.

and

_

tayP

1

/

r/

vD

This form can be interpreted in terms of difierent angular ranges! where R(0) is

the

normal-incidence

reflectioncoefficient,G describesthe variationat intermecliate

offsets

and is often referred to as the AVO gradient,whereasF dominatesthe far ofTsets.near

critical angle. Normally, the range of anglesavailablefor AVO analysisis less

than

30-40.. Therefbre,we only need to considerthe two first terms,valid fbr ansles less

t h a n . l 0 t S h u e y .I 9 8 5 , 1 :

R(P)=R(0)+Gsin2d

(4.8)

The zero-oft'setreflectivity,R(0), is controlled by the contrastin acousticimpedance

acrossan interface.The gradient, G, is more complex in terms of rock properties,

but

fiom the expressiongiven above we see that not only the contrastsin Vp and density

afrect the gradient, but also vs. The importance of the vplvs ratio (or equivalently

the Poisson'sratio) on the ofTset-dependent

reflectivity was first indicated by Koefoed

(1955). ostrander (1984) showed that a gas-filledfbrmation would

have a very low

Poisson'sratio comparedwith the Poisson'sratiosin the surroundingnongaseous

fbrmations.This would causea significantincreasein positive amplitude versusangle

at the bottom of the gas layer, and a significantincreasein negativeamplitudeversus

angle at the top of the gas layer.

4.3.2 Theeffectof anisotropy

Velocity anisotropyought to be taken into accountwhen analyzing the amplitude variation with offset(AVO) responseof gassandsencasedin shales.Although it is generally

* d

184

-

seismicinterpretation

techniques

for quantitative

Common

thought that the anisotropy is weak (10-20%) in most geological settings (Thomsen,

1986), some eff'ectsof anisotropy on AVO have been shown to be dramatic using

shale/sandmodels(Wright, 1987).In somecases,the sign of the AVO slopeor rate of

changeof amplitude with ofliet can be reversedbecauseof anisotropyin the overlying

s h a l e s( K i m e t a l . , 1 9 9 3 B l a n g y ,1 9 9 4 ) .

The elasticstiffnesstensorC in transverselyisotropic(TI) media can be expressed

in compactform as fbllows:

(Ctt - 2Coo) C r :

Cl

( c 1 1- 2 C 6 6 )

Ctr

Cn

C -

Cr:

Cr:

0

0

0

0

0

0

:

where C6,6,

I

t(Crt

C::

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

C++ 0

0

0 C++ 0

0 Cr,o

0

- Cn)

(4e)

and where the 3-axis (z-axis)lies along the axis of symmetry.

The above6 x 6 matrix is symmetric,andhasfive independentcomponents,Cr r, Crr,

Cr, C++,and C66.For weak anisotropy,Thomsen(1986) expressedthree anisotropic

parameters,t, y and 6, as a function of the five elastic components,where

Cl-Cr

a , - -

(4.10)

2Cr

Cor, C++

2C++

(4.r r)

(Cr:*C++)2-(.Cy-Calz

2C.3(Cy

(4.12)

C++)

The constants can be seento describethe fiactional differenceofthe P-wave velocities

in the vertical and horizontaldirections:

yP(90')- vp(0')

Vp(o')

( 4 .l 3 )

and thereforebest describeswhat is usually referred to as "P-wave anisotropy."

In the same manner,the constant y can be seento describethe fiactional difference

of SH-wavevelocitiesbetweenverticaland horizontaldirections,which is equivalent

to the difference between the vertical and horizontal polarizationsof the horizontally

propagatingS-waves:

185

r

4.3 AVOanalysis

T

-

- Vss(0')

V s H ( 9 0 1 - V s v ( 9 0 ) 7sH(90")

Vsn(0')

Vsv(90')

(4.14)

The physical meaningof 6 is not as clear as s and y, but 6 is the most important

parameterfbr normal moveout velocity and reflection amplitude'

Under the plane wave assumption,Daley and Hron (1911) derived theoretical fbrmulas for reflection and transmissioncoefficientsin Tl media. The P-P reflectivity in

the equation can be decomposedinto isotropic and anisotropicterms as follows:

Rpp(0): Rrpp(O)* R'rpp(0)

(4.1s)

Assuming weak anisotropyanclsmall offsets,Banik ( 1987)showedthat the anisotropic

term can be simply expressedas fbllows:

R e p p ( d )-

sin2e

-Ad

( 4 .I 6 )

Blangy (lgg4) showedthe effect of a transverselyisotropic shaleoverlying an isotropic

gas sand on offset-dependentreflectivity, for the three different types of gas sands.

He found that hard gas sandsoverlain by a soft TI shale exhibited a larger decrease

in positive amplitude with offset than if the shale had been isotropic. Similarly, soft

gas san4soverlain by a relatively hard TI shale exhibited a larger increasein negative

amplitude with offset than if the shale had been isotropic. Furthermore, it is possible

fbr a soft isotropic water sand to exhibit an "unexpectedly" Iarge AVO eff'ect if the

overlying shaleis sufficientlyanisotropic'

4.3.3 Theeffectof tuningon AVO

As mentioned in the previous section, seismic interf'erenceor event tuning can occur

as closely spacedreflectorsinterfere with each other.The relative changein traveltime

between the reflectors decreaseswith increasedtraveltime and off.set.The traveltime

hyperbolasof the closely spacedreflectorswill thereforebecome even closer at larger

ofTsets.In f-act,the amplitudes may interfere at large ofTsetseven if they do not at

small offsets.The effect of tuning on AVO has been demonstratedby Juhlin and Young

( 1993),Lin and Phair ( 1993),Bakkeand Ursin ( 1998),andDong ( 1998),amongothers.

Juhlin and Young (1993) showedthat thin layersembeddedin a homogeneousrock

can produce a significantly different AVO responsefiom that of a simple interface of

the samelithology. They showedthat, for weak contrastsin elasticpropertiesacrossthe

layer boundaries,the AVO responseof a thin bed may be approximatedby modeling

it as an interference phenomenon between plane P-waves fiom a thin layer' ln this

casethin-bed tuning affects the AVO responseof a high-velocity layer embeddedin a

homogeneousrock more than it affects the responseof a low-velocity layer.

l

186

Common

techniques

for quantitative

seismicinterpretation

Lin and Phair ( 1993)suggestedthe following expressionfor the amplitudevariation

with angle (AVA) responseof a thin layer:

(4.11)

R r ( 0 ) : r r . r o A ? ' ( c0o) sd ' R ( 6 )

where a.reis the dominant frequency of the wavelet, Af (0) is the two-way traveltirne

at normal incidencefiom the top to the baseof the thin layer, and R (0) is the reflection

coefficient fiom the top interface.

Bakke and Ursin ( 1998)extendedthe work by Lin and Phair by introducingtuning

correctionfactorsfbr a generalseismicwaveletas a function of offset. If the seismic

responsefiom the top of a thick layer is:

d(t, t') : R(t')p(r)

(4.l8)

where R(,1')is the primary reflection as a function of ofTset.t', and p(0 is the seismic

pulse as a flnction of time /, then the responsefrom a thin layer is

tl(r, y)

(4.19)

f(.y)AI(0)C(t")p'(t)

wherep'(r) is the time derivativeof the pulse,A7"(0)is the traveltimethicknessof the

thin layer at zero offset, and C (-v)is the offiet-dependentAVO tuning factor given by

c(.v):ffi['

.##"]

(4.20)

where 7(0) and Z(-r') are the traveltimes atzero ofliet and at a given nonzero offset,

respectively.The root-mean-squarevelocity VBy5, is defined along a ray path:

t

l' tt)t 'r s,

.l v \t t\|t

(4)t\

VRMS -

Jdt

0

For small velocity contrasts(Vnvs -

y), the last term in equation (4.20) can be

ignored, and the AVO tuning f'actorcan be approximatedas

r(0)

r(,r')

C(r') :v ----:--

(4.22\

For large contrast in elastic properties,one ought to include contributions fiom Pwave multiples and convertedshearwaves. The locally convertedshear wave is ofien

neglectedin ray-tracing modeling when reproductionof the AVO responseof potential

hydrocarbon reservoirs is attempted.Primaries-only ray-trace modeling in which the

Zoeppritz equationsdescribethe reflectionamplitudesis most common. But primariesonly Zoeppritz modeling can be very misleading, becausethe locally converted shear

waves often have a first-order eff-ecton the seismic response(Simmons and Backus,

1994).lnterferencebetween the convertedwaves and the primary reflectionsfiom the

187

4,3 AVOanalysis

I

(2)Single-leg

(1)Primaries

R$

(3)Double-leg

a

(4)Reverberations

andmultiplesthatmustbeincludedin AVOmodelingwhenwe have

S-waves

Figure4.5 Converted

(l) Primaryreflections;

thesenrodesto interferewith theprimaries.

thin layers.causing

(After

(4)

reverberations.

primary

(3)

and

wave;

shear

(2) single-leg

shearwaves; double-leg

:

reflected

Rsp

:

P-wave,

fiom

converted

S-wave

transmitted

andBackus,1994.)7ps

Simmons

etc.

fiom S-wave.

P-waveconverted

baseof the layersbecomesincreasinglyimportantasthe layerthicknessesdecrease.This

often producesa seismogramthat is different fiom one produced under the primariesonly Zoeppritzassumption.In this case,one shouldusefull elasticmodelingincluding

the convertedwave modes and the intrabedmultiples.Martinez (1993) showedthat

surface-relatedmultiples and P-to-SV-modeconvertedwavescan interf-erewith primary

pre-stackamplitudesand causelargedistortionsin the AVO responses.Figure 4.5 shows

the ray images of convertedS-wavesand multiples within a layer.

effects

onAVO

andwavepropagation

overburden

4.3.4 Structuralcomplexity,

Structural complexity and heterogeneitiesat the target level as well as in the overburden can have a great impact on the wave propagation.These effects include focusing

and defbcusing of the wave field, geometric spreading,transmissionlosses,interbed

and surf'acemultiples, P-wave to vertically polarized S-wave mode conversions,and

anelastic attenuation.The offset-dependentreflectivity should be corrected for these

wave propagation effects, via robust processingtechniques(see Section 4.3.6). Alternatively, these efTectsshould be included in the AVO modeling (see Sections 4.3.7

and 4.5). Chiburis (1993) provided a simple but robust methodology to correct tor

overburdeneffects as well as certain acquisition effects (seeSection a.3.5) by normalizing a target horizon amplitude to a referencehorizon amplitude. However, in more

recent years there have been severalmore extensivecontributions in the literature on

amplitude-preservedimaging in complex areasand AVO correctionsdue to overburden

effects, some of which we will summarizebelow.

188

-

Common

techniques

for quantitative

seismicinterpretation

AVO in structurally

complex areas

The Zoeppritzequationsassumea singleinterf-ace

betweentwo semi-infinitelayerswith

infinite lateralextent.In continuouslysubsidingbasinswith relativelyflat stratigraphy

(suchas Tertiarysedimentsin the North Sea),the useof Zoeppritzequationsshouldbe

valid. However,complex reservoirgeology due to thin beds,vertical heterogeneities,

faultingand tilting will violate theZoeppritzassumptions.

Resnicket at. (1987)discuss

the efl'ectsof geologic dip on AVO signatures,whereasMacleod and Martin (1988)

discussthe eff-ectsof reflector curvature.Structuralcomplexity can be accountedfor by

doing pre-stackdepth migration (PSDM). However,one should be awarethat several

PSDM routinesobtain reliable structuralimages without preservingthe amplitudes.

Grubb et ul. (2001) examined the sensitivity both in structure and amplitr-rderelated

to velocity uncertaintiesin PSDM migrated images.They performed an amplitudepreserving (weighted Kirchhof1) PSDM followed by AVO inversion. For the AVO

signaturesthey evaluatedboth the uncertaintyin AVO cross-plotsand uncertaintyof

AVO attributevaluesalong given structuralhorizons.

AVO effects due to scattering attenuation in heterogeneous overburden

Widmaier et ztl..(1996) showedhow to correct a targetAVO responsefbr a thinly layered

overburden.A thin-beddedoverburdenwill generatevelocity anisotropyand transmission lossesdue to scatteringattenuation,and theseeflects should be taken into account

when analyzinga targetseismicreflector.They combinedthe generalizedO'DohertyAnstey formula (Shapiro et ul., 1994a)with amplitude-preservingmigration/inversion

algorithms and AVO analysis to compensatefor the influence of thin-bedded layers

on traveltimes and amplitudes of seismic data. In particr-rlar,they demonstratedhow

the estimation of zero-offset amplitude and AVO gradient can be improved by correcting fbr scattering attenuationdue to thin-bed efl'ects.Sick er at. (2003) extendecl

Widmaier's work and provided a method of compensatingfor the scatteringattenuation

eflects of randomly distributed heterogeneitiesabove a target reflector. The generalized O'Doherty-Anstey formr-rlais an approximation of the angle-dependent,timeharmoniceffectivetransmissivityT for scalarwaves(P-wavesin acousticI D medium

or SH-wavesin elastic lD medium) and is given by

Tt II u Tue

( ' ' l t ) \ |i f t l A \ \ L

(4.23)

where.fis the frequency and n and p are the angle- and fiequency-dependentscattering

attenuationand phaseshift coefficients,respectively.The angle g is the initial angle of

an incident plane wave at the top surfaceof a thinly layered composite stack; L is the

thicknessof the thinly layeredstack;ft denotesthe transmissivityfbr a homogeneous

isotropic ref-erencemedium that causesa phaseshifi. Hence, the equation above representsthe relative amplitude and phasedistortions causedby the thin layers with regard

to the referencemedium. Neglectingthe quantity Zo which describesthe transmission

189

-

4.3 AVoanalysis

responsefor a homogeneousisotropic referencemedium (that is, a pttre phaseshift), a

phase-reducedtransmissivity is defined:

f ( f) o

@ t f ' o ) + t Pa()l) r

(4.24)

"

For a P-wave in an acoustic lD medium, the scatteringattenuation,cv,and the phase

coefficient,B,were derivedfrom Shapiroet al. (1994b)by Widmaier et al. (1996):

a ( . f, 0 ) :

|

tr'oot.f'

cos2oV,f I l6n:a2f2 cos2u

(4.25)

and

B(f.())-

r f'o2 l"

|V r c o s eL

gnzn: 7'z

V;+

r4)6r

t6n)02.t2cor2e

where the statistical parametersof the referencemedium include spatial correlation

length a, standarddeviationo, and mean velocity Vs. The medium is modeled as a

1D random medium with fluctuating P-wave velocities that are characterizedby an

exponential correlation function. The transmissivity (absolute value) of the P-wave

with increasingangleof incidence.

decreases

If the uncorrectedseismicamplitude(i.e., the analyticalP-wave particle displacement) is defined according to ray theory by:

I

U ( S ,G , / ) : R c - W ( r - r v )

(4 )1\

v

where U is the seismic trace, S denotes the source, G denotes the receiver, t is the

varying traveltime along the ray path, Rs is the reflection coefficient at the reflection

point M, y is the spherical divergence factor, W is the soutce wavelet, and ry is

the traveltime fbr the ray between source S, via reflection point M, and back to the

receiverG.

A reflector beneatha thin-beddedoverburdenwill have the following compensated

seismicamplitude:

u r ( s , G ,t ) :

I

f r * ( t ) *R . w 1 r- , r ;

(4 )R\

v

is givenby;

transmissivity

wherethetwo-way,time-reduced

4*(r) : irtrc(r)x Zsrvr(r)

(4 )q\

The superscriptT of Ur(S, G, r) indicatesthat thin-bed effects have been accounted

fbr. Moreover, equation (4.28) indicatesthat the sourcewavelet,W(0, is convolvedwith

the transient transmissivity both for the downgoing (i5p1 ) and the upgoing raypaths

(f n4c)between source (S), reflection point (M), and receiver (G).

190

-

Common

techniques

for quantitative

seismicinterpretation

In conclusion, equation (4.28) representsthe angle-dependenttime shift causedby

transverseisotropic velocity behavior of the thinly layeredoverburden.Furthermore,it

describesthe decreaseof the AVO responseresultingfrom multiple scatteringadditional

to the amplitude decay related to sphericaldivergence.

Widmaier eI ai. ( I 995) presentedsimilar lbrmulations for elasticP-waveAVO, where

the elasticcorrection formula dependsnot only on variancesand covariancesof P-wave

velocity, but also on S-wave velocity and density,and their correlationand crosscorrelationfunctions.

Ursin and Stovas(2002) further extendedon the O'Doherty-Anstey fbrmula and calculated scatteringattenuationfbr a thin-bedded,viscoelasticmedium. They found that

in the seismic frequency range, the intrinsic attenuationdominatesover the scattering

attenuation.

AVO and intrinsic attenuation (absorption)

Intrinsic attenuation,also referred to as anelasticabsorption,is causedby the fact that

even homogeneoussedimentaryrocks are not perf'ectlyelastic. This effect can complicatethe AVO response(e.g.,Martinez, 1993).Intrinsicattenuationcan be described

in terms of a transt'ertunction Gt.o, t) fbr a plane wave of angular frequency or and

propagationtime r (Luh, 1993):

G @ , i : exp(at12Qe* i(at lr Q) ln atI tos)

(4.30)

where Q" is the effective quality f'actorof the overburdenalong the wave propagation

path and areis an angular referencefrequency.

Luh demonstrated how to correct for horizontal, vertical and ofTset-dependent

wavelet attenuation.He suggestedan approximate, "rule of thumb" equation to calculate the relative changein AVo gradient, 6G, due to absorptionin the overburden:

ftt

3G ry :-'

Q"

(4.31)

wherei

is the peak frequency of the wavelet, and z is the zero-offsettwo-way travel

time at the studied reflector.

Carcione et al. (1998) showed that the presenceof intrinsic attenuationaffects the

P-wave reflection coefficient near the critical angle and beyond it. They also found that

the combined effect of attenuationand anisotropy aff'ectsthe reflection coefficientsat

non-normal incidence,but that the intrinsic attenuationin somecasescan actually compensatethe anisotropiceffects.In most cases,however,anisotropiceffectsare dominant

over attenuationeffects.Carcione (1999) furthermore showed that the unconsolidated

sedimentsnear the seabottom in offshore environmentscan be highly attenuating,and

that these waves will for any incidence angle have a vector attenuationperpendicular

191

r

4,3 AVOanalysis

to the sea-floorinterf'ace.This vector attenuationwill afl'ectAVO responsesof deeper

reflectors.

onAVO

etfects

4.3.5 Acquisition

The most important acquisition eff-ectson AVO measurementsinclude source directivity, and source and receivercoupling (Martinez, J993). ln particular,acquisition

footprint is a large problem fbr 3D AVO (Castagna,2001).Inegular'Eoverageat the

surfacewill causeunevenillumination of the subsurface.Theseeffectscan be corrected

for using inverseoperations.Difl'erent methodsfor this have beenpresentedin the literature(e.g.,Gassawayet a\.,1986; Krail and Shin, 1990;Cheminguiand Biondi, 2002).

Chiburis' ( 1993)method for normalizationof targetamplitudeswith a referenceamplitude provided a fast and simple way of corecting for certain data collection factors

including sourceand receivercharacteristicsand instrumentation.

dataforAVOanalysis

of seismic

4.3.6 Pre-processing

AVO processingshould preserveor restorerelative trace amplitudeswithin CMP gathers. This implies two goals: (1) reflectionsmust be correctly positionedin the subsurface; and (2) data quality should be sufficient to ensure that reflection amplitudes

contain infbrmation about reflection coefficients.

AVOprocessing

Even though the unique goal in AVO processingis to preservethe true relative

amplitudes,there is no unique processingsequence.lt dependson the complexity

of the geology.whetherit is land or marineseismicdata.and whetherthe data will

be used to extract regression-basedAVO attributes or more sophisticatedelastic

inversionattributes.

Cambois(200 l) definesAVO processingas any processingsequencethat makes

the data compatiblewith Shuey'sequation,if that is the model used for the AVO

inversion.Camboisemphasizesthat this can be a very complicatedtask'

Factorsthat changethe amplitudesof seismictracescan be groupedinto Earth effects,

acquisition-relatedeffects, and noise (Dey-Sarkar and Suatek, 1993). Earth effects

include sphericaldivergence,absorption,transmissionlosses,interbed multiples, converted phases,tuning, anisotropy, and structure. Acquisition-related eft-ectsinclude

source and receiver arrays and receiver sensitivity. Noise can be ambient or sourcegenerated.coherentor random.Processingattemptsto compensatefor or removethese

effects, but can in the processchange or distort relative trace amplitudes. This is an

important trade-off we need to consider in pre-processingfor AVO. We thereforeneed

192

r

Common

techniques

for quantitative

seismicinterpretation

to selecta basicbutrobustprocessing

scheme(e.g.,ostrander,1984;chiburis,l9g4;

Fouquet,f 990;Castagna

andBackus,1993;Yilma4 2001).

Common pre-processingstepsbefore AVO analysis

Spiking deconvolution and wavelet processing

In AVO analysiswe normally want zero-phase

data.However,the original seismicpulse

is causal,usually some sort of minimum phasewaveletwith noise.Deconvolutionis

defined as convolving the seismic trace with an inverse filter in order to extract the

impulse responsefrom the seismic trace. This procedure will restore high frequencies and therefore improve the vertical resolution and recognition of events.One can

make two-sided, non-causalfilters, or shaping filters, to produce a zero-phasewavelet

( e . g . ,L e i n b a c h ,1 9 9 5 ;B e r k h o u t ,1 9 7 7 ) .

The wavelet shapecan vary vertically (with rime), larerally (spatially),and with

offset. The vertical variations can be handled with deterministic Q-cornpensation(see

Section4.3.4). However,AVO analysisis normally carriedout within a limited time

window where one can assumestationarity.Lateral changesin the wavelet shapecan

be handledwith surface-consistent

amplitudebalancing(e.g.,Camboisand Magesan,

1997). Offset-dependentvariations are often more complicated to correct for, an4 are

attributed to both ofl.set-dependent

absorption (see Section 4.3.4), tuning efl'ects(see

Section4.3.3),andNMo stretching.NMo stretchingactslike a low-pass,mixed-phase,

nonstationaryfilter, and the eff'ectsare very difficult to eliminate fully (Cambois,2001

).

Dong (1999) examined how AVO detectability of lithology and fluids was afl'ected

by tuning and NMo stretching, and suggesteda procedure for removing the tuning

and stretching effects in order to improve AVO detectability.Cambois recommendecl

picking the reflections of interest prior to NMo corrections, and flattening them for

AVO analysis.

Spherical divergence correction

Spherical divergence, or geometrical spreading, causes the intensity and energy of

spherical waves to decreaseinversely as the square of the distance fiom the source

(Newman, 1973).For a comprehensivereview on ofTset-dependent

geometricalspreading, seethe study by Ursin ( 1990).

Surface-consistent amplitude balancing

Source and receiver eff'ectsas well as water depth variation can produce large deviations in amplitude that do not coffespond to target reflector properties.Commonly,

statistical amplitude balancing is carried out both fbr time and offset. However. this

procedure can have a dramatic efl'ect on the AVO parameters.It easily contributes

to intercept leakage and consequentlyerroneousgradient estimates(Cambois, 2000).

Cambois (2001) suggestedmodeling the expected averageamplitucle variation with

't

193

n

4.3 AVOanalvsis

off.setfbllowing Shuey's equation, and then using this behavior as a ret'erencefor

the

statisticalamplitudebalancing.

Multiple removal

One of the most deterioratingeff-ectson pre-stackamplitudes is the presenceof multiples.There are severalmethodsof filtering away multiple energy,but not all of these

are

adequatefor AVo pre-processing.The method known asfft multiple filtering, done in

the frequency-wavenumberdomain, is very efficient at removing multiples, but the

dip

in the.l-lr domain is very similar fbr near-offsetprimary energy and near-offsetmultiple

energy.Hence,primary energy can easily be removed from near tracesand not from

far

traces,resulting in an ar-tificialAVO effect. More robust demultiple techniquesinclude

linear and parabolic Radon transform multiple removal (Hampson, l9g6: Herrmann

et a1.,2000).

NMO (normal moveout) correction

A potential problem during AVO analysis is error in the velocity moveout conection

(Spratt, 1987).When extracting AVO attributes,one assumesthat primaries

have been

completely flattenedto a constanttraveltime.This is rarely the case,as there will always

be residual moveout. The reasonfor residualmoveout is almost always associatedwith

erroneousvelocity picking, and greatef'fortsshoukl be put into optimizing the estimated

velocity field (e.g.,Adler, 1999;Le Meur and Magneron,2000).However,anisorropy

and nonhyperbolicmoveoutsdue to complex overburclenmay also causemisalignments

betweennearand far off.sets(an excellentpracticalexampleon AVO and nonhyperbolic

moveout was publishedby Ross, 1997).Ursin and Ekren (1994) presenteda method

for analyzing AVO eff-ectsin the off.setdomain using time windows. This technique

reducesmoveout elrors and createsimproved estimatesof AVO parameters.One

shoulcl

be aware of AVO anomalieswith polarity shifts (classIIp, seedefinition below) during

NMO corrections,as thesecan easily be misinterpretedas residualmoveouts(Ratcliffe

and Adler, 2000).

DMO correction

DMO (dip moveout) processinggeneratescommon-reflection-pointgathers.It moves

the reflection observed on an off'set trace to the location of the coincident sourcereceiver trace that would have the same reflecting point. Therefore, it involves

shifting both time and location. As a result, the reflection moveout no longer depends

on dip, reflection-point smear of dipping reflections is eliminated, and events with

various dips have the same sracking velocity (Sheriff and Geldhart, 1995).

Shang

et al. (1993) published a rechnique on how to extract reliable AVA (amplitude variation with angle) gathers in the presence of dip, using partial pre-stack

misration.

194

-

seismicinterpretation

for quantitative

techniques

Common

Pre-stack migration

Pre-stackmigration might be thought to be unnecessaryin areaswhere the sedimentary

section is relatively flat, but it is an important component of all AVO processing.

Pre-stackmigration should be used on data for AVO analysis whenever possible,

becauseit will collapsethe diffractions at the targetdepth to be smaller than the Fresnel

zone and thereforeincreasethe lateral resolution(seeSection4.2.3; Berkhout, 1985;

Mosher et at., 1996).Normally, pre-stacktime migration (PSTM) is preferred to prestackdepth migration (PSDM), becausethe former tendsto preserveamplitudesbetter.

However, in areas with highly structured geology, PSDM will be the most accurate

PSDM routineshouldthen be applied

tool (Cambois,2001).An amplitude-preserving

, 997).

( B l e i s t e i n ,1 9 8 7 ;S c h l e i c h eer t c t l . , l 9 9 3 ; H a n i t z s c h 1

Migration fbr AVO analysis can be implemented in many different ways. Resnick

et aL. (1987) and Allen and Peddy (1993) among othershave recommendedKirchhoff migration together with AVO analysis.An alternativeapproachis to apply waveequation-basedmigration algorithms.Mosher et al. (.1996)derived a wave equation fbr

common-angle time migration and used inverse scatteringtheory (see also Weglein,

Mosher

integrationof migrationand AVO analysis(i.e.,migration-inversion).

1992'7for

et at. (1996) usecla finite-difference approachfbr the pre-stack migrations and illustrated the value of pre-stackmigration fbr improving the stratigraphicresolution, data

quality, and location accuracyof AVO targets.

of a2lseismicline

forAVO

anatysis

scheme

of pre-processing

Example

( Y i l m a z2,0 0 1 . )

geometric

scaling,

(source

processing.

( I ) Pre-stack

signature

signalprocessing

spiking deconvolutionand specffalwhitening).

(2t Sort to CMP and do sparseintervalvelocity analysis.

(3) NMO using velocity field from step2.

(4) Demultipleusing discreteRadontransform.

(5) Sort to common-offset and do DMO correction.

(6) Zero-offsetFK time migration.

(CRP) and do inverseNMO using the

(7) Sort data to common-reflection-point

velocity field from step2.

(8) Detailedvelocity analysisassociatedwith the migrateddala'

(9) NMO correclionusing velocity field from step8.

( l0) StackCRP gathersto obtainimageof pre-stackmigrateddata.Removeresidual

multiplesrevealedby lhe stacking.

( l l ) U n m i g r a t eu s i n gs a m ev e l o c i t yf i e l d a s i n s t e p6 .

( l2; Post-stackspiking deconvolution.

(13) Remigrateusing migrationvelocity field from step8.

195

4.3 AVOanalysis

E

etfects

duet0 processing

Somepitfallsin AVOinterpretation

. Waveletphase.The phaseof a seismicsectioncan be significantlyalteredduring

processing.lf rhe phaseof a sectionis not establishedby the interpreter.then AVO

anomaliesthat would be interpretedas indicativeof decreasingimpedance,for

example.can be producedat interfaceswherethe impedanceincreases(e.g.,Allen

and Peddy. I993).

. Multiple filtering. Not all demultiple techniquesare adequatelor AVO predomain,is very

processing.Multiple filtering,done in the frequency-wavenumber

efficientar removing multiples.but the dip in the/-k domain is very similar for

near-offsetprimary energy and near-offsetmultiple energy.Hence,primary energy

can easlly be removed from the near-offsettraces. resulting in an artificial AVO

effect.

. NMO correction.A potentialproblemduring AVO analysisis errorsin the velocity

moveoutcorrection(Spran. 1987).When extractingAVO attributes.one assumes

that primaries have been completely flattenedto a constanttraveltime.This is

rarely the case.as therewill alwaysbe residualmoveout.Ursin and Ekren (1994)

presenteda method for analyzing AVO effects in rhe offset domain using time

windows. This techniquereducesmoveoul errorsand createsimprovedestimates

of AVO paramerers.NMO stretch is another problem in AVO analysis. Because

the amount of normal moveout varies with arrival time. frequenciesare lowered

at large offsets compared with short offsets. Large offsets, where the stretching

effect is significant.should be muted before AVO analysis.Swan (1991), Dong

(1998) and Dong ( 1999)examinethe eft'ectof NMO stretchon offset-dependenl

reflectivity.

. AGC amplirude conection. Automatic gain control must be avoided in preprocessingof pre-stackdata beforedoing AVO analysis.

Pre-processing for elastic impedance inversion

Severalof the pre-processingstepsnecessaryfor AVO analysisare not required when

preparingdatafor elasticimpedanceinversion(seeSection4.4 for detailson the methodology). First of all, the elastic impedanceapproachallows for wavelet variations with

offset (Cambois,2000). NMO stretchcorrectionscan be skipped,becauseeachlimitedrange sub-stack(in which the waveletcan be assumedto be stationary)is matchedto its

associatedsyntheticseismogram,and this will removethe waveletvariationswith angle.

It is, however,desirableto obtain similar bandwidth fbr each inverted sub-stackcube,

since these should be comparable.Furthermore, the data used for elastic impedance

inversion are calibratedto well logs before stack,which meansthat averageamplitude

variations with offset are automatically accountedfor. Hence, the complicated procedure of reliable amplitude corrections becomes much less labor-intensivethan for

196

-

Common

techniques

for quantitative

seismicinterpretation

u

1

0

2

0

3

0

4

0

5

0

6

0

(degree)

Angle

of incidence

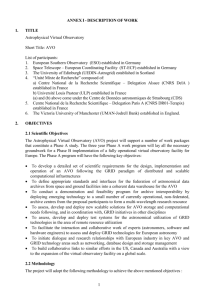

Figure4,6 AVO curvesfbr differenthalf'-space

models(i.e.,two layers one intertace).FaciesIV

is cap-rock.Input rock physicspropertie\represent

meanvaluesfor eachfacies.

standardAVO analysis.Finally,residualNMO and multiplesstill must be accountedfbr

(Cambois,2001). Misalignmentsdo not causeinterceptleakageas fbr standardAVO

analysis,but near-and far-anglereflectionsmust still be in phase.

4.3.7 AVOmodeling

andseismicdetectability

AVO analysisis normally carried out in a deterministicway to predict lithology and

fluids from seismicdata(e.g.,Smith and Gidlow, 1987;RutherfordandWilliams, 1989;

Hilterman, 1990;Castagnaand Smith, 1994;Castagnaet al., 1998).

Forward modeling of AVO responsesis normally the best way to start an AVO

analysis, as a feasibility study before pre-processing,inversion and interpretation of

real pre-stack data. We show an example in Figure 4.6 where we do AVO modeling

of difTerentlithofacies defined in Section 2.5. The figure shows the AVO curves for

different half-spacemodels, where a silty shale is taken as the cap-rock with difTerent

underlying lithofacies. For each facies, Vp, Vs, and p are extractedfrom well-log data

and used in the modeling. We observea clean sand/pureshaleambiguity (faciesIIb

and facies V) at near of1iets,whereasclean sandsand shalesare distinguishableat far

offsets.This exampledepictshow AVO is necessaryto discriminatedifferent lithofacies

in this case.

I

-T

I

197

-

4.3 AVOanalysis

CemellHiontrend

I

Cemenled

{el brino

I

0

Ceme|rbd

w/ hydruca]ton

V

Hydrocarlontr€ild

Unconsolidaled

w/ brine

Unconsolidtlsd

w/ hydrocarbon

sandscappedby

andunconsolidated

sandstone

Figure4.7 SchcgaticAVOcurvesfirr cemented

cases.

andoil-saturated

shlle.frll brine-saturated

Figure 4.7 shclwsanotherexample,where we considertwo types of clean sands,

cementedand unconsolidated,with brine versushydrocarbonsaturation.We seethat a

cemented sanclstonewith hydrocarbon saturationcan have similar AVO responseto a

brine-saturated.unconsolidatedsand.

The examplesin Figures 4.6 and 4.7 indicate how important it is to understandthe

local geology during AVO analysis.lt is necessaryto know what type of sandis expected