Early Development Instrument (EDI) Technical Report Alberta 2009*

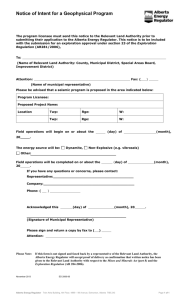

advertisement