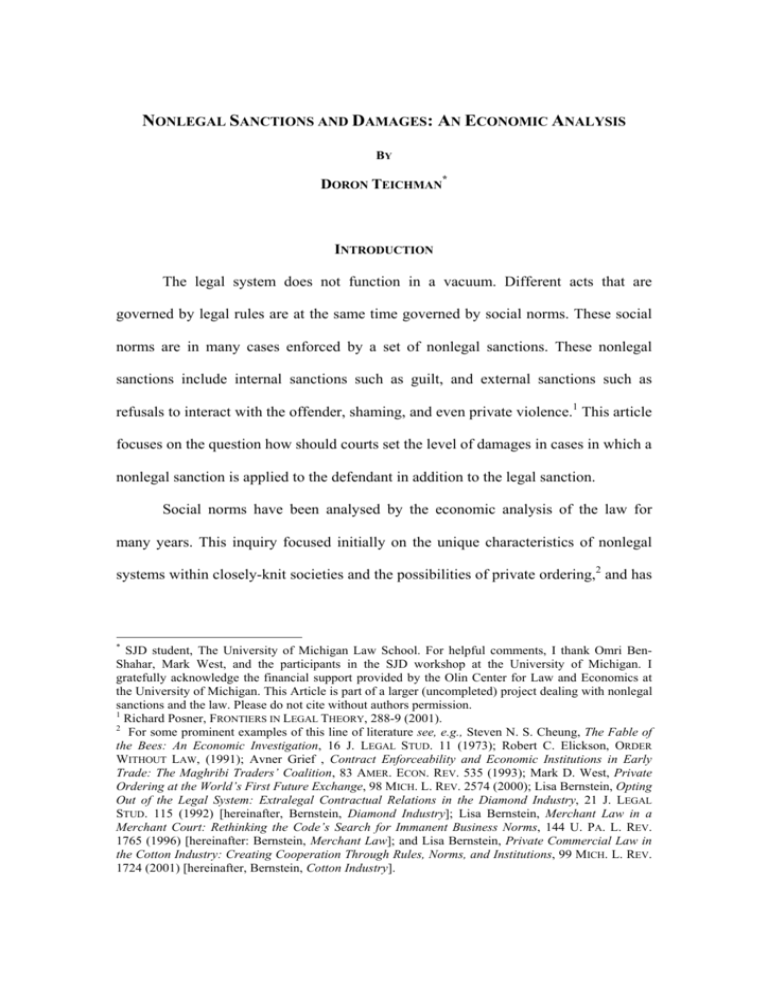

The legal system does not function in a vacuum. Different acts that

advertisement