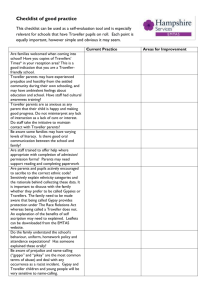

Section 2 Chapter 3 Issues of Social Justice and Equality

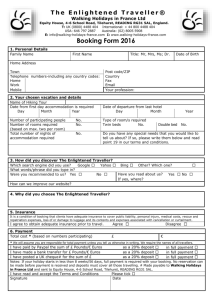

advertisement