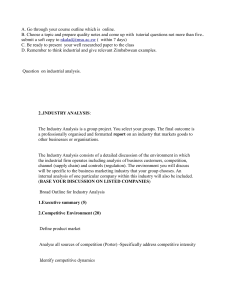

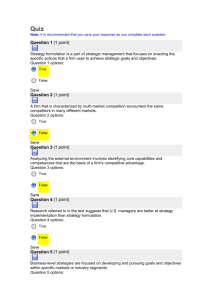

strategic management

advertisement