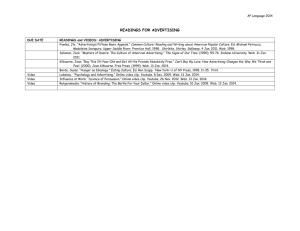

False Advertising Under the Lanham Act

advertisement

False Advertising Under the Lanham Act COURTLAND L. REICHMAN AND M. MELISSA CANNADY alse advertising under the Lanham Act is an increasingly popular cause of action because of its broad applicability and ability to remedy competitive harm. Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act1 proscribes false statements or representations that are made in commercial advertising or promotion, are likely to deceive consumers, and are likely to cause Courtland L. Reichman injury to the plaintiff. The remedies available to a plaintiff under the Lanham Act include injunctive relief, damages, corrective advertising, and attorneys’ fees, although the statute affords the court broad discretion to fashion an equitable remedy that fairly compensates the plaintiff. Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act prohibits a wide range of false or misleading statements or representations. Classic false advertisM. Melissa Cannady ing claims involve a defendant’s false or misleading statement either about its own or a competitor’s product. A variety of claims fall into these categories—statements based on testing, unsubstantiated assertions, national advertising campaigns, and verbal sales pitches to a limited number of consumers. In franchising, false advertising claims are apparently being brought with increasing frequency. Conventional franchise systems rely heavily on advertising, using it to differentiate themselves in a crowded market. The ability to redress false advertising claims is an important weapon that, unlike other intellectual property claims such as trademark infringement, both franchisees and franchisors can use. Recent cases have involved large franchisors seeking to enjoin competitors’ false comparative advertising, and franchisees seeking to enjoin competitors from poaching business with false claims. Further, developing case law supports false advertising claims by franchisees against unscrupulous franchisors. This article discusses false advertising claims under the Lanham Act. It examines the elements of a false advertising claim, including an analysis of what constitutes an actionable statement, who has standing to sue under the Lanham Act, and the remedies available to a successful plaintiff. It also highlights the considerable inconsistency in interpretations of false F Courtland L. Reichman (creichman@kslaw.com) and M. Melissa Cannady (mcannady@kslaw.com) are attorneys with the firm of King & Spalding in Atlanta, Georgia. advertising law among the federal circuit courts. The U.S. Supreme Court has yet to address false advertising law under the Lanham Act, and, as a result, the circuits have developed inconsistent and often contradictory approaches to several core issues. This article discusses the predominant approaches and evaluates possible ways to harmonize the case law. Statutory Bases for Claims The Lanham Act establishes a federal cause of action for, among other things, false advertising:2 (a)(1) Any person who, on or in connection with any goods or services, or any container for goods, uses in commerce any word, term, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof, or any false designation of origin, false or misleading description of fact, or false or misleading representation of fact, which— .... (B) in commercial advertising or promotion, misrepresents the nature, characteristics, qualities, or geographic origin of his or her or another person’s goods, services, or commercial activities, shall be liable in a civil action by any person who believes that he or she is or is likely to be damaged by such act.3 The plain language of the statute permits any person likely to be damaged to assert a claim based on a false or misleading statement of fact about a product, service, or commercial activity. This deceptively simple language has given rise to a significant body of law that is relatively unsettled and inconsistent in many respects. Most courts recite the elements of a Lanham Act false advertising claim as follows: (1) the defendant made a false or misleading statement of fact in a commercial advertisement about a product; (2) the statement either deceived or had the capacity to deceive a substantial segment of potential consumers; (3) the deception is material, in that it is likely to influence the consumer’s purchasing decision; (4) the product is in interstate commerce; and (5) the plaintiff has been or is likely to be injured as a result of the statement.4 This list of elements appears to be an historical accident. It originated in a 1974 district court decision, which did not analyze the elements and cited as its only authority a 1956 law review article that had formulated the elements based solely on pre-Lanham Act case law.5 Courts have widely repeated these elements without analysis, but have rarely (if ever) applied them as stated. These five elements do not reflect the actual, substantive elements required by courts to prove a Lanham Act false advertising claim. Claimants rarely must show “materiality” in the sense of proving that the advertisement had a likely effect on consumers’ purchasing decisions. Instead, in application, the second and third elements merge so that the Reprinted by permission of the American Bar Association ■ Volume 21, Number 4, Spring 2002 ■ Franchise Law Journal 187 “materiality” element simply requires a showing of deception, or the capacity to deceive.6 Further, although courts require some showing of “likely effect on consumer decisions,” this is in connection with the fifth element, proving the fact or the likely threat of actionable injury to the claimant.7 This interpretation hews more closely to the language of section 43(a), which does not speak of “materiality,” but requires a false or misleading statement of fact used in commercial advertising or promotion that injures, or creates a likelihood of injury to, a plaintiff. Thus, this article discusses the following elements: (1) a false or misleading statement of fact; (2) that is used in a commercial advertisement or promotion; (3) that is material, in that it deceives or is likely to deceive; (4) that is used in interstate commerce; and (5) that causes, or is likely to cause, the claimant competitive or commercial injury. In Rhone-Poulenc Rorer Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Marion Merrell Dow, Inc.,15 the court held that a drug manufacturer’s advertisements, which featured images such as two gasoline pumps and airline tickets with dramatically different prices, accompanied by the slogan “Which one would you choose?” was a literally false message, because it conveyed the inaccurate idea that the manufacturer’s drug and its competitor’s drug could be indiscriminately substituted. In Coca-Cola Co. v. Tropicana Products, Inc.,16 the court held that the images of the defendant’s television commercial advertising orange juice, that depicted an orange being squeezed and poured directly into the carton made the advertisement literally false, because it represented that the defendant’s orange juice was produced by squeezing oranges and pouring the juice directly into the carton, when in fact the juice was heated and sometimes frozen before packaging. Similarly, in S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc. v. Clorox Co.,17 the the Second Circuit considered the falsity of advertising that False or Misleading Statement of Fact focused on an image. There, the defendant’s television comTo establish a false advertising claim under the Lanham Act, mercial and print advertisements depicted two plastic storage a claimant first must prove a false or misleading statement of bags filled with water, each containing a goldfish and hangfact. To demonstrate falsity, a claimant generally must show ing upside down.18 The plaintiff’s plastic bag was shown to either: (1) that the statement is literally false, or (2) that be leaking continuously although literally true, the and at a fairly rapid rate. statement is likely to misBased on evidence prelead, confuse, or deceive sented at trial, the court consumers.8 If a statement is literally false, courts found that the defendant’s The challenged claim typically grant injunctive advertisements were literneed not make a direct relief without requiring ally false because they proof of materiality (i.e., falsely depicted both the comparison to a competitor’s that the advertisement risk and the rate of leakage product or service. deceived). If, however, a of the plaintiff’s storage statement is literally true bags.19 Claims of superiority but misleading, courts can fall on either side of usually require proof that the line between actionable falsity and nonactionable the statement has deceived, or has a tendency to deceive. “puffery.” To be actionable, the challenged claim need not make a direct comparison to a competitor’s product or serLiterally False Statements vice.20 If the advertisement asserts that a product is superior, Courts typically consider whether an advertisement is liter9 but does not refer to scientific tests as support, the plaintiff ally false to be an issue of fact. Some courts split the issue into two inquiries: (1) identification of the claim conveyed must affirmatively prove that the claim is false, i.e., that the by the advertisement; and (2) determination of whether the defendant’s product is equal or inferior.21 Such claims of 10 superiority are distinct from expressions of opinion or exagclaim is false. Courts allow the claimant to prove literal falsity based on express claims in advertisements and also geration, often called “puffery” (discussed below), which on claims that the advertisement conveys by “necessary typically do not constitute false advertising. Actionable implication.”11 “A claim is conveyed by necessary implicaclaims of superiority usually refer to specific aspects of a tion when, considering the advertisement in its entirety, the product or service (e.g., “our widget lasts longer”), whereas audience would recognize the claim as readily as if it had puffery is more general (e.g., “our widget is the best”).22 12 Where the challenged advertisement explicitly or implicitbeen explicitly stated.” If, however, the message is merely suggestive or requires viewers to make inferential leaps, it is ly represents that tests or studies prove that its product is less likely to form an appropriate basis for a literal falsity superior, the plaintiff can meet its burden in two ways.23 13 First, the plaintiff can prove that the superiority claims are challenge. The plaintiff’s burden in proving that a challenged adverliterally false because the tests used are not sufficiently relitisement is literally false depends on the nature of the claim able to permit a conclusion that the product is superior.24 Sec14 ond, the plaintiff can meet its burden by showing that the involved and the context in which the claim is made. For example, a visual image, or a visual image combined with an tests used, even if reliable, did not establish the proposition audio component, may make an advertisement literally false. for which they were cited.25 188 Franchise Law Journal ■ Spring 2002, Volume 21, Number 4 ■ Reprinted by permission of the American Bar Association For example, in Castrol, Inc. v. Quaker State Corp., the defendant’s television commercial, which asserted that “tests prove” that its motor oil provides better protection against engine wear at start-up, was literally false. The district court heard five days of expert testimony at trial in determining whether the tests upon which the defendant relied supported the superiority claims in the defendant’s commercial. In the end, the court found that it did not need to consider the tests’ reliability because they did not establish the proposition for which the defendant cited them.26 lawyers but at a lower price were held to be mere “puffery” and not actionable as false advertising.36 Similarly, a claim that “You’re in good hands with” an insurer was held to be nonactionable puffery because it was general, subjective, and could not be proven true or false.37 Again, the context of the claim is important when determining whether an advertisement claim is mere puffery. For example, a clothing manufacturer’s claims that its product was the “best waterproof golf suit available” or the “best way to keep dry” were more than puffery when juxtaposed with a comparison to the competitor’s product, and the manufacturMisleading Statements er had no evidence of comparison testing.38 The line between actionable statements of fact and mere A statement may be actionable false advertising even if it is puffery can be difficult to find. For example, in Pizza Hut, literally true. “Statements that are literally true or ambiguInc. v. Papa John’s International, Inc.,39 Pizza Hut based its ous but which nevertheless have a tendency to mislead or false advertising action on Papa John’s slogan, “Better deceive the consumer are actionable under the Lanham Ingredients. Better Pizza.” Pizza Hut challenged the slogan Act.”27 Such claims may implicitly convey a false impression, may be misleading in context, or may simply be standing alone and in conjunction with comparative repredeceptive when viewed by consumers.28 sentations regarding the quality of the competitor’s dough Courts universally hold that if an advertisement is literaland sauce. Papa John’s had asserted that its tomato sauce ly true but allegedly miswas made with “fresh, leading, the claimant has vine-ripened tomatoes” an additional burden and its dough with “clear of proving that the adverfiltered water,” while The context of the claim tisement has deceived Pizza Hut’s sauce came is important when determining or has a tendency to from “remanufactured deceive.29 As discussed in tomato paste,” and its whether an advertisement greater detail below, a dough used “whatever claim is mere puffery. claimant must prove comes out of the tap.” 40 The jury found that the materiality by extrinsic statements in Papa John’s evidence, such as a conads were literally true but sumer survey or market misleading, and the trial court concluded that the misleading research, demonstrating how consumers actually reacted to ads had so “tainted” the slogan that it enjoined further use the advertising.30 altogether.41 Opinion and Puffery On appeal, the Fifth Circuit held that the slogan “Better A third category of statements includes opinion and puffery, Ingredients. Better Pizzas,” standing alone, was nonactionwhich are not actionable. For a statement to be actionable able puffery because it was not a quantifiable or verifiable under section 43(a), it must be a statement of fact, as opposed fact, and thus not a claim upon which consumers would justo mere opinion or bald assertions of superiority.31 A statetifiably rely.42 But the court upheld the jury’s finding that, ment of fact is one that “(1) admits of being adjudged true or when viewed in combination with Papa John’s sauce and false in a way that (2) admits of empirical verification.”32 dough ads, the slogan was misleading. The court reasoned “Puffery,” in contrast, that when used in conjunction with those ads, the slogan became a verifiable statement regarding the quality of the comes in at least two possible forms: (1) an exaggerated, blustering, ingredients, and that there was sufficient evidence in the and boasting statement upon which no reasonable buyer would be justified in relying; or (2) a general claim of superiority over comrecord to support the conclusion that the advertisements parable products that is so vague that it can be understood as nothwere misleading.43 As discussed more fully below, however, ing more than a mere expression of opinion.33 the Fifth Circuit nonetheless reversed and directed entry of Thus, a claim that “Less Is More” in advertising for turf judgment for Papa John’s because Pizza Hut had failed to grass was held to be nonactionable puffery because it was the prove materiality. type of generalized boasting upon which no reasonable buyer Commercial Advertising or Promotion would rely.34 But a related claim describing the product with the phrase “50% Less Mowing” was held to be actionable The second element of a false advertising claim is that the false advertising because it was a specific and measurable false or misleading statement of fact must appear in “comclaim of superiority, apparently based on product testing.35 mercial advertising or promotion.”44 Recent decisions generStatements in a collection agency’s advertisement implying ally rely on the following definition of “commercial that the agency offered the same collection services as advertising or promotion”: Reprinted by permission of the American Bar Association ■ Volume 21, Number 4, Spring 2002 ■ Franchise Law Journal 189 (1) commercial speech; Thus, in cases that do not involve conventional, anonymous mass advertising, courts generally examine evidence on the nature of the industry to determine whether the state(3) for the purpose of influencing consumers to buy the defendant’s ment was disseminated to enough of the relevant “public” goods or services; and to constitute advertising or promotion. “[B]oth the required (4) that is disseminated sufficiently to the relevant purchasing publevel of circulation and relevant ‘consuming’ or ‘purchaslic to constitute “advertising” or “promotion” within that industry, ing’ public addressed by the dissemination of false inforeven if not made in a “classical advertising campaign.”45 mation will vary according to the specifics of the The first three parts of the definition are intended to ensure industry.”53 Where there are a relatively limited number of that advertising or promotion excludes noncommercial speech potential purchasers in a particular market, for example, that is entitled to a higher degree of protection under the First even a single promotional presentation to an individual purAmendment.46 In addition to the general commercial speech chaser may be actionable as “commercial advertising and element, the definition adds the standing requirement that the promotion.”54 In Seven-Up Co. v. Coca-Cola Co., the Fifth Circuit held that a soft drink manufacturer’s sales presentadefendant must be in “commercial competition” with the tions to representatives of eleven independent bottlers were plaintiff. This arises out of First Amendment concerns that the sufficiently disseminated to the relevant purchasing public Lanham Act not be used to impinge free speech.47 The “commercial speech” element, however, should be read to mean to be “commercial advertising or promotion” within the only that advertising and promotions that are fair game under soft drink industry because the presentation materials were the First Amendment are actionable. There seems to be little specifically developed and designed to target independent justification for adding a “competition” requirement that does bottlers—the manufacturer’s purchasers—and convince not appear in the text of the Lanham Act.48 them to change brands.55 Furthermore, oral statements also This definition also requires the statement to have been may constitute “advertismade in “advertising or ing or promotion,” particpromotion.” Courts have ularly if that is the struggled to define “advercustomary method of tising and promotion.” On advertising in a particular The definition of one end of the spectrum, industry.56 “advertising or promotion” As these decisions conventional mass advertisillustrate, whether a paring campaigns—such as should start with the plain ticular communication where a company runs meaning of these words. constitutes “advertising or newspaper advertisements, promotion” is a highly television commercials, or fact-specific inquiry, other promotions to influwhich often turns on the ence large numbers of nature of the industry. Other examples of actionable “adveranonymous consumers to buy its products or services—cleartising or promotion” include: ly are actionable advertising or promotion. At the other end, a • In Avon Products, Inc. v. S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc.,57 the private negotiation between two businesspeople, absent other 49 court held that Avon’s dissemination of lists of alternative circumstances, would not be actionable. Between these two poles fall a wide array of statements that may or may not qualuses of its “Skin-So-Soft” bath oil and other materials ify as “advertising or promotion,” depending on a variety of touting the bath oil as an insect repellent was advertising factors, including the context in which the statement was and promotion under the Lanham Act because Avon’s made, the relevant audience, the specific industry involved, business relies exclusively upon promotion by its sales and the extent of dissemination or publication. representatives. The definition of “advertising or promotion” should start • In Gordon & Breach Science Publishers S.A. v. American with the plain meaning of these words.50 The U.S. Supreme Institute of Physics,58 the court held that nonprofit scientifCourt has instructed that when construing a statute, the first ic societies’ distribution at a librarians’ conference of step “is to determine whether the language at issue has a allegedly misleading comparative survey results, which plain and unambiguous meaning with regard to the particular favored the societies’ publications, and e-mails to librarians (prospective purchasers of the publications) were dispute in the case.”51 Webster’s Dictionary defines “advertiscommercial advertising under the Lanham Act because ing” as, among other things, “the act of calling something to the survey was explicitly promotional in nature. the attention of the public especially by paid announce• In National Artists Management Co. v. Weaving,59 the ments,” and “promotion” as, among other things, “the furcourt concluded that the defendant’s telephone calls to therance of the acceptance and sale of merchandise through roughly ten people about reasons for terminating their advertising, publicity, or discounting.”52 These capacious definitions seem to include more limited communication used to relationship with plaintiff were “advertising or promopromote or sell products or services, so long as the commution” because, in the theater-booking industry, services are nication is aimed at the relevant consuming “public.” promoted by word of mouth and a network of telephone (2) by a defendant who is in commercial competition with the plaintiff; 190 Franchise Law Journal ■ Spring 2002, Volume 21, Number 4 ■ Reprinted by permission of the American Bar Association contacts, and the industry is “indisputably small and closely interconnected.” By contrast, the following examples were held not to be “advertising or promotion”: • In First Health Group Corp. v. BCE Emergis Corp.,60 the Seventh Circuit concluded that representations by the defendant’s executives and lawyers during private contract negotiations were not advertising within the meaning of the Lanham Act. • In Sports Unlimited, Inc. v. Lankford Enterprises, Inc.,61 the Tenth Circuit held that the defendant’s distribution of a reference sheet describing unfavorable customer comments about the plaintiff’s work did not constitute commercial advertising or promotion because the defendant distributed the sheet to only two people for whom the plaintiff was already working. • In Fashion Boutique of Short Hills, Inc. v. Fendi USA, Inc.,62 the court held that store employees’ allegedly disparaging comments about another store to twelve customers and nine undercover investigators were not “advertising or promotion” under the Lanham Act, where thousands of customers comprised the relevant purchasing public. • In Gillette Co. v. Norelco Consumer Products Co.,63 the court determined that claims in a package insert accompanying an electric razor that the razor provided a “closer, more comfortable shave” were not commercial advertising or promotion because the statements were inside the package and therefore did not affect the purchaser’s decision to buy the product. Materiality A plaintiff must demonstrate that the false or misleading advertising or promotion at issue is “material.”64 Materiality centers on whether the false or misleading advertisement deceives or is likely to deceive.65 Such materiality generally is established when the advertisement deceives, or has the capacity to deceive, a substantial segment of potential consumers about a relevant quality or characteristic of the product or service. Some older cases discuss materiality in terms of whether the representation involved an “inherent” quality, characteristic, or nature of the product.66 However, this requirement is not rooted in the language of the statute, which on its face includes no materiality or “inherency” requirement, and courts typically do not impose it.67 Whether the representation is likely to influence consumers’ decisions is more appropriately addressed as part of the injury requirement. The plaintiff’s burden of establishing materiality differs depending on the type of statement involved and the defendant’s intent, as discussed below. Literally False Statements Where the statement at issue is literally false, courts presume that the advertisement was material: “With respect to materiality, when the statements of fact at issue are shown to be literally false, the plaintiff need not introduce evidence on the issue of the impact the statements had on consumers.”68 This principle is tied directly to section 43(a), which on its face does not require an additional showing of deception, and thus reflects that a literally false statement by its very nature has the capacity to deceive consumers. Nonetheless, defendants should be permitted to present evidence rebutting the presumption of materiality by showing that consumers were not, in fact, deceived by the advertisement. Misleading Statements When a claim is literally true but misleading, the claimant must show the nature of the message actually conveyed to consumers, which turns on the public’s reaction to the advertisement.69 “The plaintiff may not rely on the judge or the jury to determine, based solely upon his or her own intuitive reaction, whether the advertisement is deceptive.”70 Instead, the evidence must demonstrate that the advertising or promotion deceived a substantial portion of its audience.71 The requirement of actual deception is grounded in practicality: it is difficult to determine that a literally true advertisement was unlawfully “misleading” without reference to whether actual consumers were misled. “[W]here the advertisement is literally true, [public perception] is often the only measure by which a court can determine whether a commercial’s net communicative effect is misleading.”72 The type of evidence necessary to prove materiality varies depending on the nature of the case and the relief requested.73 In general, surveys are the preferred vehicle.74 However, evidence showing how consumers actually reacted, such as letters, calls, and affidavits, can also show consumer deception.75 Surveys Surveys are the predominant and most widely accepted method of proving materiality.76 Even where the claimant believes that it can rely on a literal falsity claim or seeks only an injunction (that requires less evidence of materiality), counsel is wise to develop credible survey evidence. Courts place great weight on properly conducted surveys, which often determine appellate results. In JTH Tax, Inc. v. H&R Block Eastern Tax Services, Inc.,77 for example, the Fourth Circuit considered whether H&R Block’s false characterization of certain loans as tax “refunds” constituted false advertising under section 43(a). The court relied heavily on a survey showing that 21.7 percent of consumers regarded the phrase “refund amount” as more effective than the term “loan.” In addition, the survey evidence showed that consumers associate loans with numerous unfavorable conditions and obligations, as opposed to a “refund.” Thus, without addressing whether the challenged statements were literally false or merely misleading, the Fourth Circuit upheld the district court’s finding that use of the term “refund” to advertise a noninterest-bearing loan was likely to deceive a reasonable consumer.78 In Pizza Hut, Inc. v. Papa John’s International, Inc.,79 the Fifth Circuit considered materiality based on Pizza Hut’s survey results. As discussed above, Pizza Hut sued Papa John’s for false advertising based on Papa John’s $300 million Reprinted by permission of the American Bar Association ■ Volume 21, Number 4, Spring 2002 ■ Franchise Law Journal 191 advertising campaign, which included the slogan, “Better Standing and Injury Ingredients. Better Pizzas.” Although the court concluded The Lanham Act provides that a false advertiser “shall be that the slogan was misleading when viewed in combination liable in a civil action by any person who believes that he or with other misrepresentations, it determined that Pizza Hut she is or is likely to be damaged by such act.”86 This element encompasses both a standing and an injury requirement. had presented insufficient evidence of materiality because Pizza Hut failed to prove that the Papa John’s ads had the Standing tendency to deceive consumers. The court rejected Pizza The plain meaning of “any person” in section 43(a) encomHut’s attempted use of Papa John’s tracking surveys, which passes both competitors and consumers that can show harm showed that 48 percent of respondents believed that Papa from the false advertising. However, courts have consistently John’s used better ingredients than other pizza chains, rearejected consumer standing to sue for false advertising under soning that this was not sufficiently probative of materiality, the Lanham Act.87 Courts generally root this conclusion in because the surveys did not indicate whether the participants’ section 45 of the Lanham Act, which provides that the statute conclusions resulted from the advertisements at issue, from was enacted “to protect persons engaged in . . . commerce their own eating experiences, or both.80 The percentage of consumers who must be deceived by an against unfair competition.”88 Based on section 45, courts advertisement varies depending on the context and nature of almost universally hold that the Lanham Act requires some the survey, but courts generally will find materiality if 20 showing of a potential for commercial or competitive injury. percent or more of survey respondents were deceived. For The U.S. Supreme Court has never considered standing under example, in JTH Tax,81 the court held that a consumer survey section 43(a)(1)(B), and the federal circuits have been sharply showing that 20 percent of respondents were deceived by the criticized for their inconsistent decisions on this issue.89 Although courts have consistently held that there must be defendant’s advertisement was sufficient to establish materisome commercial injury, approaches differ on whether the ality. The court in Johnson & Johnson-Merck Consumer plaintiff must be a competitor of the defendant. For example, Pharmaceutical Co. v. Rhone-Poulenc Rorer Pharmaceutithe Second Circuit has held that “a section 43 plaintiff need cals82 held that a survey finding that only 7.5 percent of respondents were deceived not be a direct competitor” by the defendant’s adverof the defendant, but tisement was not suffiinstead must merely allege cient, but noted that 20 the potential for commerCourts have consistently percent would have been cial or competitive injury.90 rejected consumer standing The Third Circuit has also sufficient. Also, in Novarrecognized that a noncomtis Consumer Health, Inc. to sue for false advertising petitor is not necessarily v. Johnson & Johnsonunder the Lanham Act. precluded from bringing a Merck Consumer Pharmafalse advertising claim ceutical Co., 83 the court ruled that survey evidence under the Lanham Act.91 In the Ninth Circuit, on showing that only 15.5 the other hand, to have standing to sue for false advertising percent of the respondents were misled was sufficient to under the Lanham Act, the plaintiff must “allege commercial show that, under the Lanham Act, a substantial portion of the injury based upon a misrepresentation about a product, and intended audience was deceived. also that the injury was ‘competitive,’ i.e., harmful to the Willful or Bad Faith Conduct plaintiff’s ability to compete with the defendant.”92 The Seventh and Tenth Circuits have followed the Ninth Circuit’s Although not all circuits have spoken on the issue, several lead in holding that to have standing for a Lanham Act false have held that if the defendant violated the Lanham Act willadvertising claim, the plaintiff must be a competitor of the fully or in bad faith, a plaintiff is not required to provide condefendant and allege a discernible competitive injury.93 sumer survey or other extrinsic evidence in order to prove Moreover, as discussed above, most circuits include (without materiality: analysis) in the definition of “commercial advertising or proIn some circuits, if the defendant “intentionally set out to deceive motion” a requirement that the defendant is in commercial the public,” using “deliberate conduct” of an “egregious nature” in light of the advertising culture of the marketplace in which the competition with the plaintiff.94 defendant competes, a presumption arises that consumers were, in In Conte Bros. Auto, Inc. v. Quaker State-Slick 50, Inc.,95 fact, deceived, dispensing with the need for the plaintiff to commisthe Third Circuit articulated a standing test, noting that sion a consumer survey.84 “there exists no single overarching test for determining the This presumption is justified by the rationale that actual constanding to sue” under the Lanham Act. Under the Conte fusion is difficult to prove, and where a defendant intentionally Bros. standard, a court should consider: seeks to deceive consumers, it is fair to infer that consumers (1) The nature of the plaintiff’s alleged injury: Is the injury “of a were, in fact, deceived.85 Of course, the defendant is free to type that Congress sought to redress in providing a private remedy for violations of the [Lanham Act]”? rebut this by demonstrating an absence of consumer confusion. 192 Franchise Law Journal ■ Spring 2002, Volume 21, Number 4 ■ Reprinted by permission of the American Bar Association (2) The directness or indirectness of the asserted injury. (3) The proximity or remoteness of the party to the alleged injurious conduct. (4) The speculativeness of the damages claim. (5) The risk of duplicative damages or complexity in apportioning damages.96 or she is likely to be injured by the false advertising.103 “The statute demands only proof providing a reasonable basis for the belief that the plaintiff is likely to be damaged as a result of the advertising.”104 Thus, a likelihood of injury will not be presumed.105 “The type and quantity of proof required to show injury and causation has varied from one case to another depending on the particular circumstances.”106 As discussed above, survey evidence need not be submitted in every case to prove a likelihood of injury; injury sometimes will be a fair inference based on the nature of the false statement and of the competition between the parties. Under the Conte Bros. test and other Lanham Act jurisprudence, it is highly unlikely that a plaintiff who is merely a consumer would have standing to bring a claim for false advertising under the Lanham Act, because a consumer cannot show commercial injury. However, it does not Remedies necessarily follow that a plaintiff who is a consumer of the The Lanham Act provides for broad injunctive and monetary product or service, but who also has a commercial or comrelief.107 The type of evidence necessary to prove substantive petitive interest, would not have standing to bring a false elements of the offense differs depending on the relief advertising claim. sought. A plaintiff requesting only injunctive relief need Of particular relevance to franchising, the Second Circuit make no greater showing than is necessary to satisfy the recently held that a trademark licensee is not precluded from materiality element of the cause of action. Thus, for literally suing its licensor for false advertising if the licensor makes false claims, no additional evidence is necessary, and for false claims to promote a competing product or falsely dismisleading claims, a tendency to deceive consumers must be parages the licensee’s product.97 The court determined that “[t]he licensor’s sole enjoyment of the goodwill in the established.108 By contrast, when the plaintiff seeks damages, it generally must prove actual confusion or deception arising licensed mark does not entitle it to make false claims to profrom the violation.109 Finally, other forms of monetary relief mote its own product, allegedly to the detriment of its 98 can be available in some jurisdictions without demonstrating licensee.” “Trademark licensees have been able to sue competitors under section 43(a), . . . and we see no reason why a actual deception. false advertising claim may not be brought by a licensee just Injunctive Relief because the alleged violator is the licensor.”99 This case fits comfortably within precedent requiring False advertising claims usually include prayers for injuncsome competitive injury, but it also could have far-reaching tive relief, at least in part because the plaintiff’s burden of implications. A franchisee, proof is lower than that who is a trademark licennecessary to receive damsee of the franchisor, ages. Injunctive relief should have standing to requires a showing only assert false advertising that the defendant’s repCourts have broad discretion claims against the franresentations about its in fashioning injunctive relief chisor if the franchisor is product have a tendency competing against the franto deceive consumers, in false advertising cases. chisee at some level. This which is presumed where could occur, for example, the statement is literally if the franchisor is using false.110 Courts have broad disfalse advertising to sell cretion in fashioning injunctive relief in false advertising national accounts, or to convince new franchisees to join a cases.111 The most common form is an injunction prohibiting separate system operated by the franchisor. If the franchisor the defendant from further distribution of the false advertisoperates through a dual distribution system, owning some ing. In some cases, the court may also enter an injunction stores and franchising others, the franchisor’s risk increases. ordering the defendant to correct the problems that its false advertising created. For instance, in Rhone-Poulenc Rorer Injury Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Marion Merrell Dow, Inc.,112 the The Lanham Act affords a claim to a plaintiff who “believes” defendant was required to undertake corrective advertising to that it is, or is likely to be, damaged by the challenged violaremedy its false advertising, which said that its pharmaceutition.100 However, both case law and common sense dictate that “despite the use of the word ‘believes,’ something more cal product could be freely substituted for its competitor’s than a plaintiff’s mere subjective belief that he is injured or product. The court ordered the defendant to take steps neceslikely to be damaged is required. . . .”101 On the other hand, sary to explain to its sales representatives, physicians, pharonly threatened, not actual, injury need be established to macists, and patients the differences between its product and obtain injunctive relief.102 its competitor’s product, including that the defendant’s prodGenerally, the case law requires a claimant to show that he uct was not approved to treat angina.113 Reprinted by permission of the American Bar Association ■ Volume 21, Number 4, Spring 2002 ■ Franchise Law Journal 193 Monetary Damages Once a violation of section 43(a) has been established, the plaintiff is entitled subject to the principles of equity, to recover (1) defendant’s profits, (2) any damages sustained by the plaintiff, and (3) the costs of the action. . . . In assessing profits the plaintiff shall be required to prove defendant’s sales only; defendant must prove all elements of cost or deduction claimed. In assessing damages the court may enter judgment, according to the circumstances of the case, for any sum above the amount found as actual damages, not exceeding three times such amount. If the court shall find that the amount of recovery based on profits is either inadequate or excessive the court may in its discretion enter judgment for such sum as the court shall find to be just, according to the circumstances of the case. Such sum in either of the above circumstances shall constitute compensation and not penalty. The court in exceptional cases may award reasonable attorney fees to the prevailing party.114 This provision confers broad discretion upon the district court.115 Several forms of monetary relief are possible, including the amount of profits lost as a result of the defendant’s false advertising (marketplace damages), the defendant’s profits gained as a result of its false advertising (unjust enrichment), amounts necessary for corrective advertising, and attorneys’ fees. Importantly, although the Lanham Act permits courts to increase damages, punitive damages are not available for violation of section 43(a).116 do not require actual confusion for marketplace damages, they appear to be mistaken: It is difficult to see how a plaintiff can prove that false advertising directly and proximately led to a decline in its profits if it cannot show that consumers stopped purchasing the plaintiff’s goods because of the defendant’s deception. Attributing a decline in profits to the defendant’s misconduct would appear speculative without such evidence. Where the challenged advertisement is deliberately false, some courts have dispensed with the need for actual consumer confusion.121 For example, the Ninth Circuit has held that the “[p]ublication of deliberately false comparative claims gives rise to a presumption of actual deception and reliance,” reasoning that: The expenditure by a competitor of substantial funds in an effort to deceive consumers and influence their purchasing decisions justifies the existence of a presumption that consumers are, in fact, being deceived. He who has attempted to deceive should not complain when required to bear the burden of rebutting a presumption that he succeeded.122 Defendant’s Profits Another form of potential monetary relief is recovery of the defendant’s profits resulting from the false advertising. The circuits are split on whether such damages are available without proof of deliberate misconduct. The Second, Third, Sixth, and D.C. Circuits have concludMarketplace Damages ed that a plaintiff must prove that the defendant acted willfulMost courts require proof of actual consumer deception ly before it can recover the defendant’s profits.123 The Eighth and Ninth Circuits have to award the plaintiff its suggested that willful con“marketplace damages,” duct is required. 124 The which are defined as lost dominant rationale for profits and loss of goodMost courts require proof requiring willful misconwill. Actual deception is of actual consumer deception duct is “to limit what may required because it shows be an undue windfall to the that the defendant’s misto award the plaintiff its plaintiff, and prevent the conduct caused actual “marketplace damages.” potentially inequitable harm in the markettreatment of an ‘innocent’ place. 117 Conceptually, actual confusion is part of or ‘good faith’ infringer.”125 However, the Fifth, causation, because false Seventh, Tenth, and Eleventh Circuits do not generally advertising can only cause monetary damage if consumers require intentional misconduct.126 For example, the Eleventh were deceived into buying the defendant’s product in lieu of Circuit has held that a plaintiff need not demonstrate intenthe plaintiff’s product. tional misconduct to obtain an award of the defendant’s profThere is, however, disagreement among the circuits on its.127 Similarly, the Seventh Circuit has held that actual this issue. The Ninth Circuit has held that actual confusion confusion is not necessary to recover on an unjust enrichis not necessary and that “the preferred approach allows the ment theory.128 Instead, these circuits have adopted a flexible district court in its discretion to fashion relief, including approach. The Eleventh Circuit has made clear that “all monmonetary relief, based on the totality of the circumetary awards under Section 1117 are ‘subject to the princistances.”118 The Eleventh Circuit has suggested the same result, stating that “all monetary awards under Section 1117 ples of equity,’ . . . and no hard and fast rules dictate the form are ‘subject to the principles of equity,’ and contrary to the or quantum of relief.”129 The flexible approach seems most appropriate. The award assertions of both parties, no hard and fast rules dictate the of defendant’s profits should be left to the trial court’s discreform or quantum of relief.”119 Often, however, courts do not distinguish between “marketplace damages” and other tion, taking into account the overall equities of the case and forms of monetary relief, for which proof of actual confuthe parties’ respective conduct. In most instances, an award sion is less important.120 To the extent that these decisions of the defendant’s profits will, indeed, be predicated on 194 Franchise Law Journal ■ Spring 2002, Volume 21, Number 4 ■ Reprinted by permission of the American Bar Association intentional misconduct. However, there are cases where the defendant’s conduct may not rise to the level of “willfulness,” but nonetheless it would be inequitable for the defendant to keep profits derived from unlawful conduct. The concern of limiting windfall judgments and preventing inequitable treatment can be handled on a case-by-case basis under traditional principles of equity, without the need to establish an inflexible rule requiring intentional misconduct. Corrective Advertising and Damage Control Courts also may award the plaintiff compensation for its own corrective advertising efforts undertaken before final adjudication of the dispute. 130 In these cases, the court often requires the plaintiff to prove that its advertising strategy was actually corrective and undertaken in response to the defendant’s false advertising.131 In addition, courts have awarded damages for prospective corrective advertising expenditures. To recover these, the plaintiff often must prove that: (1) the expenditures are corrective, i.e., responsive to the defendant’s false advertising;132 (2) the expenditures are a surrogate for measuring the plaintiff’s actual damages;133 and (3) the plaintiff is unable to undertake a corrective advertising campaign concurrently with the wrong that it seeks to redress in court.134 Attorneys’ Fees The Lanham Act empowers a court to award the prevailing party reasonable attorneys’ fees in “exceptional cases.”135 The prevailing party has the burden of demonstrating the exceptional nature of the case by “clear and convincing evidence.”136 While many courts have held that an exceptional case is one where the defendant’s acts can be characterized as malicious, fraudulent, deliberate, bad faith, or willful, some courts have simply characterized the misconduct as “very egregious.”137 As a practical matter, attorneys’ fees are difficult to recover unless the defendant intended to deceive or refused to withdraw the advertising or promotion once it became aware of the deception. Conclusion False advertising under the Lanham Act is an increasingly popular cause of action because it applies to such a broad variety of statements in diverse factual settings. False advertising claims may be particularly useful in franchising, given the importance of advertising in promoting franchise brands and the ability of franchisees to bring actions, especially where the competitive paths—and swords—of franchisor and franchisee cross. Endnotes 1. 15 U.S.C. § 1125. 2. 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a). 3. Id. 4. See, e.g., Clorox Co. Puerto Rico v. Procter & Gamble Commercial Co., 228 F.3d 24, 33 n.6 (1st Cir. 2000); Pizza Hut, Inc. v. Papa John’s Int’l, Inc., 227 F.3d 489, 495 (5th Cir. 2000); Balance Dynamics Corp. v. Schmitt Indus., 204 F.3d 683, 689 (6th Cir. 2000); Cook, Perkiss and Liehe, Inc. v. N. Cal. Collection Serv., Inc., 911 F.2d 242, 244 (9th Cir. 2000); United Indus. Corp. v. Clorox Co., 140 F.3d 1175, 1180 (8th Cir. 1998); Johnson & Johnson-Merck Consumer Pharm. Co. v. Rhone-Poulenc Rorer Pharm., Inc., 19 F.3d 125, 129 (3d Cir. 1994); Skil Corp. v. Rockwell Int’l Corp., 375 F. Supp. 777 (N.D. Ill. 1974). 5. Skil Corp.., 375 F. Supp. at 783 (citing Weil, Protectability of Trademark Values Against False Competitive Advertising, 44 CAL. L. REV. 527, 537 (1956)). 6. See, e.g., Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 497; see also discussion of materiality below. 7. See, e.g., Warner-Lambert Co. v. Breathasure, Inc., 204 F.3d 87 (3d Cir. 2000). 8. S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc. v. Clorox Co., 241 F.3d 232, 238 (2d Cir. 2001); United Indus. Corp., 140 F.3d at 1179; Southland Sod Farms v. Stover Seed Co., 108 F.3d 1134, 1139–40 (9th Cir. 1997). 9. See, e.g., Clorox Co. Puerto Rico, 228 F.3d at 34. 10. Id. 11. Id. at 34-35. 12. Id. at 35. 13. See, e.g., id.; United Indus. Corp., 140 F.3d at 1175. 14. See Pizza Hut, Inc. v. Papa John’s Int’l, Inc., 227 F.3d 489, 495 (5th Cir. 2000) (“When construing the allegedly false or misleading statement to determine if it is actionable under section 43(a), the statement must be viewed in the light of the overall context in which it appears.”); United Indus. Corp., 140 F.3d at 1180. 15. 93 F.3d 511, 516 (8th Cir. 1996). 16. 690 F.2d 312, 318 (2d Cir. 1982). 17. 241 F.3d 232 (2d Cir. 2001). 18. Id. at 235-37. 19. Id. at 239. 20. Southland Sod Farms v. Stover Seed Co., 108 F.3d 1134, 1145 (9th Cir. 1997). 21. See Castrol, Inc. v. Quaker State Corp., 977 F.2d 57, 63 (2d Cir. 1992); Avon Prod., Inc. v. S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc., 984 F. Supp. 768, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1997). In addition, courts have held that a claim that is unsupported but that is not literally false or deceptive does not violate the Lanham Act. See Am. Home Prod. Corp. v. Procter & Gamble Co., 871 F. Supp. 739, 758 (D.N.J. 1994) (“[T]he absence of acceptable tests or other proof substantiating an advertising claim does not alleviate a Lanham Act plaintiff’s burden of showing that a challenged advertisement is false or misleading. Thus, a plaintiff must affirmatively prove that the claim in question is false or misleading, not merely that it is unsubstantiated.”) (quotations and citations omitted); see also Johnson & Johnson-Merck Consumer Pharm. Co. v. Rhone-Poulenc Rorer Pharm., Inc., 19 F.3d 125, 129 (3d Cir. 1994); Sandoz Pharm. Corp. v. Richardson-Vicks, Inc., 902 F.2d 222, 228 (3d Cir. 1990). 22. See Cook, Perkiss and Liehe, Inc. v. N. Cal. Collection Serv., Inc., 911 F.2d 242, 246 (9th Cir. 2000) (“The common theme that seems to run through cases considering puffery in a variety of contexts is that consumer reliance will be induced by specific rather than general assertions. Advertising which merely states in general terms that one product is superior is not actionable.”) (citations and quotations omitted). 23. Castrol, Inc., 977 F.2d at 63. 24. Id. 25. Id. Of course, the plaintiff could also prove that the defendant’s claim of “tests prove X,” for example, is literally false if in fact the defendant never conducted any tests. 26. Id. at 63-64. 27. United Indus. Corp. v. Clorox Co., 140 F.3d 1175, 1182 (8th Cir. 1998). 28. Id. at 1180. 29. See, e.g., Clorox Co. Puerto Rico v. Procter & Gamble Commercial Co., 228 F.3d 24, 33 (1st Cir. 2000). 30. Id.; Gordon & Breach Science Publishers S.A. v. Am. Inst. of Physics, 859 F. Supp. 1521, 1532 (S.D.N.Y. 1994). 31. See, e.g., Pizza Hut, Inc. v. Papa John’s Int’l, Inc., 227 F.3d 489, 496 (5th Cir. 2000) (collecting cases); Groden v. Random House, 61 Reprinted by permission of the American Bar Association ■ Volume 21, Number 4, Spring 2002 ■ Franchise Law Journal 195 F.3d 1045, 1051 (2d Cir. 1995) (stating that when a statement is “obviously a statement of opinion,” it cannot “reasonably be seen as stating or implying provable facts”). 32. Presidio Enter., Inc. v. Warner Bros. Distrib. Corp., 784 F.2d 674, 679 (5th Cir. 1986); see also Southland Sod Farms v. Stover Seed Co., 108 F.3d 1134, 1145 (9th Cir. 1997). 33. Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 496-97. 34. Southland Sod, 108 F.3d at 1134. 35. Id. 36. Cook, Perkiss and Liehe, Inc. v. N. Cal. Collection Serv., Inc., 911 F.2d 242, 246 (9th Cir. 2000) (finding that reasonable consumers would not interpret the plaintiff’s claim as a factual claim upon which they could rely). 37. See Bologna v. Allstate Ins. Co., 138 F. Supp.2d 310, 323 (E.D.N.Y. 2001). 38. W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc. v. Totes, Inc., 788 F. Supp. 800 (D. Del. 1992). 39. 227 F.3d 489, 491 (5th Cir. 2000). 40. Id. at 492. 41. Id. at 493-94. 42. Id. at 498-99. 43. Id. at 501-02. 44. See 17 U.S.C. § 1125(a); Seven-Up Co. v. Coca-Cola Co., 86 F.3d 1379, 1383 (5th Cir. 1996). 45. Gordon & Breach Science Publishers S.A. v. American Inst. of Physics, 859 F. Supp. 1521, 1532 (S.D.N.Y. 1994); see also Sports Unlimited, Inc. v. Lankford Enter., Inc., 275 F.3d 996, 1004-05 (10th Cir. 2002) (using these four factors to determine whether challenged conduct constitutes “commercial advertising or promotion”); Coastal Abstract Serv., Inc. v. First Am. Tit. Ins. Co., 173 F.3d 725, 734 (9th Cir. 1999); Seven-Up Co., 86 F.3d at 1384. 46. Gordon & Breach, 859 F. Supp. at 1536. Although several courts have adopted the Gordon & Breach four-part test, including incorporation of the First Amendment “free speech” doctrine, courts have expressed appropriate skepticism about whether such requirements should be added to the plain language of the statute. See, e.g., First Health Group v. BCE Emergis Corp., 269 F.3d 800, 803 (7th Cir. 2001) (“We have serious doubts about the wisdom of displacing the statutory text in favor of a judicial rewrite with no roots in the language Congress enacted.”). 47. Gordon & Breach, 859 F. Supp. at 1532. 48. See First Health Group, 269 F.3d at 803. 49. Id. at 804. 50. See, e.g., Barnhart v. Sigmon Coal Co., Inc., 122 S. Ct. 941, 950 (2002) (“As in all statutory construction cases, we begin with the language of the statute.”); First Health Group, 269 F.3d at 803; Seven-Up Co., 86 F.3d at 1384 (“Courts have noted that we should give the terms ‘advertising’ and ‘promotion’ their plain and ordinary meanings.”). 51. Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., 519 U.S. 337, 340 (1997) (citing United States v. Ron Pair Enter., Inc., 489 U.S. 235, 240 (1989)). 52. WEBSTER’S NINTH NEW COLLEGIATE DICTIONARY 59,941 (1984). 53. Seven-Up Co. v Coca Cola, 86 F.3d 1379, 1385 (5th. Cir. 1996). 54. Id. at 1386; Mobius Mgmt. Sys., Inc. v. Fourth Dimension Software, Inc., 880 F. Supp. 1005 (S.D.N.Y. 1994) (holding that a single letter from a computer software manufacturer to a potential customer could constitute “advertising or promotion”). 55. Seven-Up Co., 86 F.3d at 1386. 56. See, e.g., Nat’l Artists Mgmt. Co., Inc. v. Weaving, 769 F. Supp. 1224, 1234-35 (S.D.N.Y. 1991). 57. 984 F. Supp. 768, 795 (S.D.N.Y. 1997). 58. 905 F. Supp. 169 (S.D.N.Y. 1995). 59. 769 F. Supp. 1224, 1234-35 (S.D.N.Y. 1991). 60. 269 F.3d 800, 804 (7th Cir. 2001); but see Mobius Mgmt. Sys., Inc. v. Fourth Dimension Software, Inc., 880 F. Supp. 1005 (S.D.N.Y. 1994) (holding that a single letter from a computer software manufacturer to a potential customer could constitute “advertising or promotion”). 61. 275 F.3d 996, 1004-05 (10th Cir. 2002). 62. 942 F. Supp. 209 (S.D.N.Y. 1996). 63. 946 F. Supp. 115 (D. Mass. 1996). 64. JTH Tax, Inc. v. H&R Block East Tax Serv., Inc., 28 Fed. App. 207 (4th Cir. 2002). 65. Pizza Hut, Inc. v. Papa John’s Int’l, Inc., 227 F.3d 489, 502 (5th Cir. 2000); Sandoz Pharm. Corp. v. Richardson-Vicks, Inc., 902 F.2d 222, 228-29 (3d Cir. 1990). 66. See, e.g., Coca-Cola Co. v. Tropicana Prod., Inc., 690 F.2d 312 (2d Cir. 1982). 67. See Jean Wegman Burns, Confused Jurisprudence: False Advertising Under the Lanham Act, 79 B.U. L. REV. 807, 871 (Oct. 1999) (noting that Congress never included a materiality or “inherent” requirement in § 43(a)). Nonetheless, courts in the Second Circuit continue to recite and apply the “inherent quality or characteristic” language. See, e.g., S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc. v. Clorox Co., 241 F.3d 232, 238 (2d Cir. 2001). 68. Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 497; see also S.C. Johnson & Son, 241 F.3d at 232; Clorox Co. Puerto Rico v. Procter & Gamble Commercial Co., 228 F.3d 24 (1st Cir. 2000). 69. See Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 497; Southland Sod Farms v. Stover Seed Co., 108 F.3d 1134, 1140 (9th Cir. 1997); Johnson & JohnsonMerck Consumer Pharm. Inc. Co. v. Rhone-Poulenc Rorer Pharm., 19 F.3d 125 (3d Cir. 1994). 70. Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 497 (quotation omitted); see also Clorox Co. Puerto Rico, 228 F.3d at 37; Johnson & Johnson v. Smithkline Beecham Corp., 960 F.2d 294, 297 (2d Cir. 1992). 71. See United Indus. Corp. v. Clorox Co., 140 F.3d 1175, 1182 (8th Cir. 1998). 72. Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 503 n.13. 73. Id. at 497. 74. See Clorox Co. Puerto Rico, 228 F.3d at 36; Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 497. 75. Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 497. 76. See, e.g., id. at 503 n.3 (“[T]he success of a plaintiff’s implied falsity claim usually turns on the persuasiveness of a consumer survey.”). 77. JTH Tax, Inc. v. H&R Block East Tax Serv., Inc., 28 Fed. App. 207 (4th Cir. 2002). 78. Id. 79. 227 F.3d 489 (5th Cir. 2000). 80. Id. at 503. 81. 128 F. Supp. 2d 926 (E.D. Va. 2001), aff’d, 28 Fed. App. 207 (4th Cir. 2002). 82. 19 F.3d 125, 135-36 n.14 (3d Cir. 1994). 83. 129 F. Supp. 2d 351, 367 (D.N.J. 2000) (citing Coca-Cola Co. v. Tropicana Prod., Inc., 690 F.2d 312, 317 (2d Cir. 1982)). 84. Clorox Co. Puerto Rico v. Procter & Gamble Commercial Co., 228 F.3d 24 36 n.9 (1st Cir. 1998); see also United Indus. Corp., 140 F.3d at 1183; Johnson & Johnson-Merck Consumer Pharm. Co. v. Rhone-Poulenc Rorer Pharm., Inc., 19 F.3d 125 (3d Cir. 1994); Resource Dev., Inc. v. Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Found., Inc., 926 F.2d 134 (2d Cir. 1991); U-Haul Int’l, Inc. v. Jartran, Inc., 793 F.2d 1034 (9th Cir. 1986). 85. See Resource Dev., 926 F.2d at 140. 86. 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a) (emphasis added). 87. See, e.g., Seven-Up Co. v. Coca-Cola Co., 86 F.3d 1379, 1383 n.5 (5th Cir. 1996) (“[W]e have found no case which suggests that ‘consumers’ have standing under § 43(a).”); Stanfield v. Osborne Indus., Inc., 52 F.3d 867, 873 (10th Cir. 1995) (“[T]hus, to have standing for a false advertising claim, the plaintiff must be a competitor of the defendant and allege competitive injury.”); Serbin v. Ziebart Int’l Corp., 11 F.3d 1163, 1177 (3d Cir. 1993) (holding that the consumers, as noncommercial plaintiffs, do not have standing under the Lanham Act); Colligan v. Activities Club of New York, Ltd., 442 F.2d 686 (2d Cir. 1971) (analyzing the legislative history and purpose behind § 43(a) and concluding that consumers lacked standing to bring action under the Lanham Act); Bacon v. Southwest Airlines Co., 997 F. Supp. 775, 780 (N.D. Tex. 1998) (holding that there is no private cause of action for consumers under the false advertising prong of the Lanham Act); see also James S. Wrona, False Advertising and Consumer Standing Under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act: Broad Consumer Protection Legislation or a Narrow Pro-Competitive Measure?, 47 RUTGERS L. REV. 1085 196 Franchise Law Journal ■ Spring 2002, Volume 21, Number 4 ■ Reprinted by permission of the American Bar Association (1995) (concluding that most courts agree that consumers do not have standing to sue, although various rationales are still employed). 88. 15 U.S.C. § 1127. 89. See Burns, supra note 67, at 888 (advocating that federal false advertising law should develop around the “unifying principle of consumer welfare,” § 43(a)(1)(B)’s “true purpose”). “As a result of Congress’s lack of clarity, the courts remain without guidance on the central issue in any statutory construction: the purpose behind section 43(a). . . . The federal law of false advertising needs fundamental change. Currently, the case law under section 43(a)(1)(B) is a collection of inconsistent, ad hoc decisions offering no predictability or unifying philosophy.” Id. at 833-34, 888. 90. Havana Club Holding, S.A. v. Galleon S.A., 203 F.3d 116, 130 (2d Cir. 2000) (quoting Berni v. Int’l Gourmet Restaurants of Am., Inc., 838 F.2d 642, 648 (2d Cir. 1988) (citations omitted)). 91. See Joint Stock Soc’y v. UDV N. Am., Inc., 266 F.3d 164 (3d Cir. 2001) (“Section 43(a) is intended to provide a private remedy to a commercial plaintiff who meets the burden of proving that its commercial interests have been harmed by a competitor’s false advertising. This is not to say that a non-competitor never has standing to sue under this provision; rather the focus is on protecting commercial interests that have been harmed by a competitor’s false advertising and securing to the business community the advantages of reputation and good will by preventing their diversion from those who have created them to those who have not.”) (citations omitted). 92. Barrus v. Sylvania, 55 F.3d 468, 470 (9th Cir. 1995) (quoting Waits v. Frito-Lay, Inc., 978 F.2d 1093 (9th Cir. 1992)). 93. See, e.g., Stanfield v. Osborne Indus., Inc., 52 F.3d 867, 873 (10th Cir. 1995); L.S. Heath & Son, Inc. v. AT&T Info. Sys., Inc., 9 F.3d 561 (7th Cir. 1993) (denying standing to a noncompetitor of the defendant). 94. See, e.g., Sports Unlimited, Inc. v. Lankford Enter., Inc., 275 F.3d 996, 1004-05 (10th Cir. 2002); Gordon & Breach Science Publishers S.A. v. Am. Inst. of Physics, 859 F. Supp. 1521, 1532 (S.D.N.Y. 1994). 95. 168 F.3d 221, 230-31 (3d Cir. 1998). 96. Id. at 233; see also Procter & Gamble Co. v. Amway Corp., 242 F.3d 539, 562-63 (5th Cir. 2001). 97. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. v. Marvel Enter., Inc., 277 F.3d 253 (2d Cir. 2002). 98. Id. 99. Id. 100. 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a). 101. Johnson & Johnson v. Carter-Wallace, 631 F.2d 186, 189-90 (2d Cir. 1980). 102. See, e.g., Warner-Lambert Co. v. Breathasure, Inc., 204 F.3d 87, 93 (3d Cir. 2000). 103. See, e.g., id. 104. Carter-Wallace, 631 F.2d at 190; Warner-Lambert Co., 204 F.3d at 93. 105. Id. 106. Ortho Pharm. Corp. v. Cosprophar, Inc., 32 F.3d 690 (2d Cir. 1994); Warner-Lambert Co., 204 F.3d at 95. 107. See 15 U.S.C. §§ 1116 (injunctive relief); 1117 (monetary relief). 108. See, e.g., Pizza Hut, Inc. v. Papa John’s Int’l, Inc., 227 F.3d 489, 497 (5th Cir. 2000); American Council, 185 F.3d at 618 (“Although plaintiff need not present consumer surveys or testimony demonstrating actual deception, it must present evidence of some sort demonstrating that consumers were misled.”). 109. See generally George Basch Co., Inc. v. Blue Coral, Inc., 968 F.2d 1532, 1537 (2d Cir. 1992). 110. See, e.g., Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 497; American Council, 185 F.3d at 618. 111. See 15 U.S.C. § 1116(a). 112. 93 F.3d 511, 516 (8th Cir. 1996). 113. Id. at 514, 516. 114. 15 U.S.C. § 1117(a). 115. Burger King Corp. v. Mason, 855 F.2d 779 (11th Cir. 1988). 116. See, e.g., Babbit Elec., Inc. v. Dynascan Corp., 38 F.3d 1161 (11th Cir. 1994); Harper House, Inc. v. Thomas Nelson, Inc., 889 F.2d 197 (9th Cir. 1989); Getty Petroleum Corp. v. Bartco Petroleum Corp., 858 F.2d 103 (2d Cir. 1988); Metric & Multistandard Components Corp. v. Metric’s, Inc., 635 F.2d 710 (8th Cir. 1980). 117. Balance Dynamics Corp. v. Schmitt Indus., 204 F.3d 683, 690 (6th Cir. 2000). 118. Southland Sod Farms v. Stover Seed Co., 108 F.3d 1134, 1146 (9th Cir. 1997). 119. Mason, 855 F.2d at 783. 120. See infra. 121. See, e.g., Southland Sod, 108 F.3d at 1146. 122. U-Haul Int’l, Inc. v. Jartran, Inc., 793 F.2d 1034, 1040-41 (9th Cir. 1986); see also Resource Dev., Inc. v. Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Found., Inc., 926 F.2d 134 (2d Cir. 1991) (“[U]pon a proper showing of such deliberate conduct, the burden shifts to the defendant to demonstrate the absence of consumer confusion.”); Porous Media Corp. v. Pall Corp., 110 F.3d 1329, 1334-35 (8th Cir. 1992) (applying rule only in context of comparative advertising where plaintiff’s product was specifically targeted). 123. See George Basch Co., Inc. v. Blue Coral, Inc., 968 F.2d 1532, 1540 (2d Cir. 1992); Securacomm Consulting, Inc. v. Securacom Inc., 166 F.3d 182, 190 (3d Cir. 1999); Frish’s Restaurants, Inc. v. Elby’s Big Boy, 849 F.2d 1012, 1015 (6th Cir. 1988); ALPO Petfoods, Inc. v. Ralston Purina Co., 913 F.2d 958, 968 (D.C. Cir. 1990) (Thomas, J.). 124. See Minnesota Breeders, Inc. v. Schell & Kampeter, Inc., 41 F.3d 1242, 1247 (8th Cir. 1994); Gracie v. Gracie, 217 F.3d 1060, 1068 (9th Cir. 2000). 125. George Basch Co., 968 F.2d at 1540. 126. See Rolex Watch USA, Inc. v. Meece, 158 F.3d 816 (5th Cir. 1998); Web Printing Controls Co., Inc. v. Oxy-Dry Corp., 906 F.2d 1202, 1205-06 (7th Cir. 1990); Estate of Bishop v. Equinox Int’l Corp., 256 F.3d 1050 (10th Cir. 2001); Burger King Corp. v. Mason, 855 F.2d 779, 781 (11th Cir. 1988). 127. Mason, 855 F.2d at 781. 128. Web Printing, 906 F.2d at 1205-06. 129. Mason, 855 F.2d at 783. 130. PBM Prod., Inc. v. Mead Johnson & Co., 174 F. Supp. 2d 417, 420 (E.D. Va. 2001) (citing ALPO Petfoods, Inc. v. Ralston Purina Co, 913 F.2d 958, 969 (D.C. Cir. 1990) (“In a false advertising case . . . actual damages . . . can include . . . the costs of any completed advertising that actually and reasonably responds to the defendant’s offending ads.”)). 131. See JTH Tax, Inc. v. H&R Block East Tax Services, Inc., 128 F. Supp. 2d at 946–47; see also Balance Dynamics Corp. v. Schmitt Indus., 204 F.3d 683, 691 (6th Cir. 2000). (“[I]t is unreasonable to expect a business person faced with a Lanham Act violation to sit idly by until a customer manifests actual confusion. The law should encourage quick responses and the mitigation of damage, and should not require parties to suffer an injury before trying to prevent it. Moreover, a rule allowing recovery for damage control costs upon the likelihood of actual confusion does not risk an ‘undeserved windfall’ to the plaintiff since such an award would not speak to the underlying marketplace damages.”). 132. Id. (refusing the plaintiff’s claim for advertising expenses because the plaintiff failed to show that the cost of advertising was a loss or that the advertising was intended to ameliorate the effects of the defendant’s advertising, where the plaintiff sought advertising costs for all of its franchises, not just the affected ones, and where the plaintiff had committed to its advertising strategy before the defendant began its false advertising). 133. See U-Haul Int’l, Inc. v. Jartran, Inc., 793 F.2d 1034, 1037 (9th Cir. 1986) (awarding plaintiff twice the sum of the cost of defendant’s false advertising campaign and the cost of plaintiff’s corrective advertising, as a surrogate for plaintiff’s actual damages). 134. PBM Prod., Inc., 174 F. Supp. 2d at 420 (citations omitted). 135. 15 U.S.C. § 1117. 136. Balance Dynamics Corp., 204 F.3d at 686. 137. Id. at 691. Reprinted by permission of the American Bar Association ■ Volume 21, Number 4, Spring 2002 ■ Franchise Law Journal 197