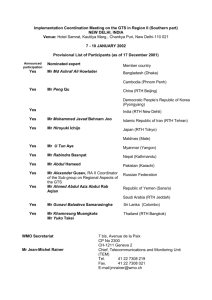

From Academic Research to Marketing Practice

advertisement