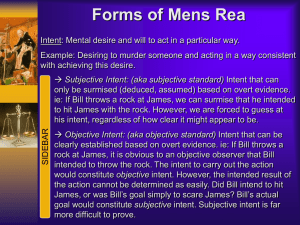

MISSING THE MARK THE MISPLACED RELIANCE ON INTENT IN

advertisement