Final Review Guide (with notes on solutions)

advertisement

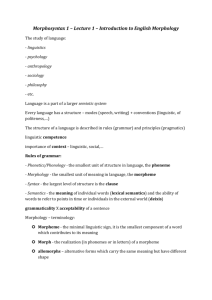

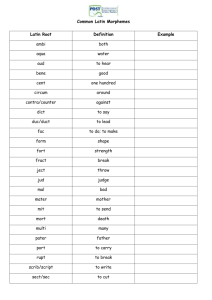

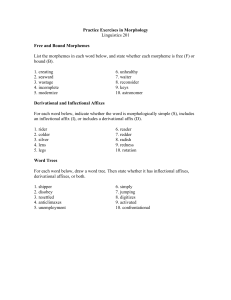

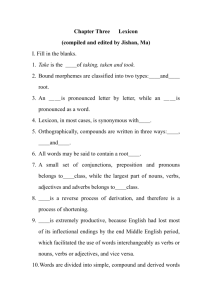

Course Overview for Final May 8 (Tuesday), 8-10 AM (Bartlett Room 301) Course goals: o Learn about the methodology (and formalisms) used by linguists to explore the following questions: What do you “know” when you know a language? How do we map sounds to words, words to sentences, and words / sentences to meanings? How are languages put together? How can languages be different from each other? How must they be similar? o You will develop your skills of analytic reasoning (make abstractions from data, form hypotheses, test the hypotheses, propose a theory based on your observations). - 1.0 - The material we have covered addresses these course goals. Since the final is designed to address your mastery of the course goals, we’ll review how what we’ve learned fits into the goals of the course. o This review guide is intended to be representative of the types of questions you will see on the final. Big Question 1: What do you know when you know a language? How are languages put together? (AKA, let’s apply some formalisms) You know a LEXICON and a GRAMMAR. o The lexicon is just a list of words. You have to actively acquire these words (e.g., your parent or caretaker points to an object and tells you what it is). o Your grammatical knowledge is subconscious and is not acquired consciously. It is the task of the linguist to investigate (using the scientific method) the details of the grammar of human language. o Languages differ in having different words (different lexicons), but also the rules contained in their grammars may be different… - But one of the most interesting questions in linguistics is how grammars can be different and how they must be similar. We return to this issue in Section 3 where we discuss the question of linguistic universals. Our main focus in the class has been the structure of the grammar. o Question 1: How can we tell that there is some innate, universal “mental organ” of language (AKA, Universal Grammar)? Children are able to acquire language rapidly and with little input (‘Poverty of the Stimulus’). People can produce sentences they’ve never heard before. 1 o Question 2: What are the components of grammar? See below. 1.1 Syntax - On a specific level, the syntax-related part of grammar tells you how words (of some category) can combine to form larger units, called constituents. - We determined a set of PHRASE STRUCTURE RULES for English. The following rules are the ones that you will be asked to apply on the test. Our PS (Phrase Structure) Rules: PS Rules for NPs PS Rule for Sentences NP (D) (A) N (PP) S NP VP PS Rules for VPs PS Rules for PPs VP VP PP PP P (NP) VP V (NP) PS Rule for Conjunction XP XP and XP - (1) (2) (3) You learned: o How to apply the above rules to create a phrase structure tree for a given sentence. o How to associate different phrase structure trees with different meanings, in the case of ambiguous sentences. I return to the issue of ambiguity (syntactic and morphological) in Section 2. o How to determine, using tests, whether a string of words in a particular sentence. is a constituent or not: Coordination and swapping Quizzical intonation Substitution o What structural roles different parts of a tree have. HEAD: Word that gives a phrase its category and core meaning. Is not optional. • V is head of VP, N is head of NP, P is head of NP. SISTER: A constituent is sister to another constituent if they have the same mother (e.g., if you can trace one line from both constituents and land at the same place). • The notion of ‘sisterhood’ is very important when it comes to determining how syntactic structure relates to meaning. We’ll come back to this in Section 2. Syntax Mechanics Practice Please draw a tree for the following sentence ‘John and the student walked to class.’ In your tree for (1), please circle the head of every phrase and tell me what constituent the PP to class is sister to. Given the sentence ‘John and the student walked to class’: - Use one constituency test to show me that to class is a constituent. - Use a different test to show me that student walked is not a constituent. 2 1.2 Morphology - The morphology-related part of grammar tells you how morphemes (free and bound) can combine to form new words. - You learned: o How to determine and write a morphological rule for the combination of free and derivational morphemes. o How to tell the difference between a derivational and inflectional morpheme. There are four ways to tell. You should be able to apply these diagnostics. 1 Derivational morphemes can (but do not have to) change the category of the word. 2 All derivational morphemes must combine to form a free morpheme before inflectional morphemes can join (this is called the MORPHEME ORDERING PRINCIPLE. I return to it in Section 3). 3 Derivational morphemes are “picky” about the morphemes they can combine with. E.g., -able will combine with some verbs but not all verbs. By contrast, inflectional morphemes will combine with every word of particular category (e.g., there is a past tense form for every verb, there is a plural form for every noun). 4 Inflectional morphemes have grammatical meanings: they tell you when the action happened, how many nouns were involved, etc. Derivational morphemes have a wider range of meanings. o How to identify draw a morphological tree representing the order in which different morphemes combine. You can do this both for combinations of free morphemes (COMPOUNDING) and for combinations of free and bound morphemes. Rules for drawing trees: (1) Don’t violate any rules. Only combine things that you’re allowed to combine. (2) Make sure every pair of morphemes you combines sounds like a good word (free morpheme) of English. If in doubt, write me a note. o What structural roles different parts of a morphological tree have? HEAD: In English, the right-most morpheme with a category (so, either a derivational or free morpheme) in a word, which tells you the category of the entire word. Any word will only have one head (like a person…). • RIGHT-HAND HEAD RULE BASE: The free morpheme to which a derivational morpheme attaches. A single word will have as many bases as it has derivational morphemes. 3 Morphology, cont. … We determined a rules for derivational morphemes in English. Here is my list. Verb + -able verb Adjective + -en verb Adjective + -ness noun Verb + -er noun Un + verb verb Un + adjective adjective Re + verb verb (1) Morphology Mechanics Practice Please draw morphological trees for the following words: a. unforgiveable b. long jumper (treat long jump as a compound noun) c. rebuilder a. A 3 A A un 3 V A forgive -able Head: -able Bases: forgive, forgiveable Deriv. morphemes: un-, -able. b. N 3 V N 3 -er A V long jump Head: -er Base: long jump Deriv. morphemes: -er c. N 3 V N 3 -er V V re build Head: -er Base: build, rebuild Deriv. morphemes: re-, -er 4 (3) Are the underlined morphemes in the following words derivational or inflectional? How can you tell? Unforgiveable rewrite hunter s 1.3 - Phonology and Phonotactics The phonology-related part of grammar tells you how the sound system of a language is organized (AKA, which phones are phonemes? Which are allophones of a phoneme?). If two phones are allophones of each other, the phonology tells you the circumstances under which the allophones appear. o This part of the grammar also tells you how to syllabify words. This is called the phonotactic part of grammar. 1.3.1 - Phonology You learned: o The differences between PHONEMES and ALLOPHONES. PHONEME: the underlying (or, mental representation) of a sound. ALLOPHONE: the way in which the phoneme is pronounced in a particular phonological environment (i.e., when surrounded by certain other sounds). The allophone may look like the phoneme or different from it. o How to think in terms of features, and describe a set of phones as having particular features in common. o How to approach a set of phonology data and determine: Whether two sounds (or, two sets of sounds) are individual phonemes (or sets of phonemes) or allophones of each other. The environment in which a phoneme becomes its “different-looking” allophone. Two individual phonemes One phoneme, two allophones /α/ /β/ /α/ [α] [β] [α] [β] o You also learned how to put all of these individual pieces together and write a phonological rule entirely in features. 5 Introduction to Linguistic Theory ! Final 5 10 points Mechanics Practice [D@ fAlowiN sEntIns hæzPhonology th uw mijniNz. In w2n, D@ pôEp@zIS2nl fôeIz ‘‘An D@ " (1) teIbl There is some feature that is held by every phone in the following list except ’’ mAdIfaIz ‘‘Elf.’’ gIv D@ paôs 2v D@ sEntIns Dæt kh owôIspAndz thone uwphone. Dæt Tell me the uniting feature and the phone that doesn’t have this feature. (There may be " h mijniN An D@ bæk 2v DIs p eIÃ.] more than one possible answer). (1) a. [aɪ, aʊ, ɔɪ,ofæ] The picture the elf on the table broke. b. [w, θ, ŋ, h, z] c. [m, r, l, j, ð] 8 points (2) Please re-write the following rule in terms of features. d/ [tʃ, dʒ] / [i, u] The/t,following words are___ transcribed from a speaker of an undisclosed language. (3) Complete the following phonology problem: 6 [upSa] [wZulza] [udsaSku] [IwzgumZi] [UmÃ] [ugSonz] [spadS] [ogÙa] [umzudÙi] [SIlÃ] ‘if ’ ‘you’ ‘look’ ‘closely’ ‘you’ ‘will’ ‘see’ ‘that’ ‘there’ ‘are’ [uNÃ] [ditÙomz] [Ùids] [mÃoNzu] [slilZ] ‘no’ ‘minimal’ ‘pairs’ ‘at’ ‘all’ -voice +voice Compare the sounds that are [ +strident ] with the sounds that are [ +strident ]. If these groups of sounds constitute different phonemes, then circle a minimal pair that shows this. If they are allophones, then write the rule that controls their distribution. Be sure to write this rule with features. (4) Complete the following phonology problem: [kunezulu] ‘heaven’ [nzwetu] ‘our’ [zevo] ‘then’ [ʒima] ‘stretch’ [kesoka] ‘to be cut’ [kasu] ‘emaciation’ [aʒimola] [lolonʒi] [zeŋɡa] ‘alms’ ‘to wash houses’ ‘to cut’ [ŋkoʃi] [nselele] ‘lion’ ‘termite’ Compare the phones [s,z] to [ʃ,ʒ]. Are they different phonemes? Or is one set allophones of the other? If they stand in a phoneme-allophone relationship, write a phonological rule in terms of features. 1.3.2 Phonotactics - The phonotactic part of grammar tells you how phones can be arranged into syllables in a given language. o Which phones can occur together in an onset? In what order? o Which phones are good syllable nuclei? o Which phones can occur together in a 3coda? In what order? - You learned: o How to draw a syllabification tree given the phonotactic constraints of English. o You learned which phones can be syllable nuclei. [all vowels], [n, l, m, r] | | | | 6 o You learned the phonotactic constraints of English, which govern which phones can appear together in an onset and/or coda. Phonotactic Constraints - (1) Nucleus Constraint: Syllable nuclei must be [+sonorant]. Coda Voicing Constraint 1: In a coda, if the first of two consonants is [-voiced], the second consonant must also be [-voiced]. Coda Voicing Constraint 2: In a coda, if the first of two consonants is [+voiced, -sonorant], the second consonant must also be [+voiced]. Maximum Onset Principle: Syllabify such that onsets are as large as possible and codas are as small as possible. Onset Phonotactic Principle: In an onset, if one consonant is [+sonorant], it must come second. Phonotactics Mechanics Practice Can the following words be syllabified? If not, tell me which part(s) of the word prevent it from being syllabified according to English phonotactic constraints. a. [bɛθlɡlɪbz] | This word can be syllabified. σ σ σ ty ty t1y O N O N O N C 1 11 111 1 [b ɛ θ l ɡ l ɪ b z] | b. [klævrɡrɛp] This word cannot be syllabified. There is no way that [vr] can be syllabified as a coda. [rg] also cannot be an onset (‘Onset Phonotactic Principle.’) 2.0 - Big Question 2: How do we map words and strings of words to meanings? We’ve addressed this problem primarily by looking at cases of AMBIGUITY, where our structural rules of syntax and morphology can generate two (or more) different structures for a single word or single sentence. o Each structure has a different meaning. - For syntactic ambiguity, remember the Principle of Modification: A PP modifies the phrase (VP) or head (N) that it is sister to. - For morphological ambiguity, remember the following observation: Each time two morphemes (free + free, or free + bound) come together in a tree, they form a new possible 7 free morpheme. It is this free morpheme (whatever it means) that goes on to combine as a single unit with any other morphemes in the tree. Ambiguity Practice (1) The following word has two possible meanings. Please draw a tree for each meaning and paraphrase the meaning of each tree. unlockable A 2 V A 2-able V V un lock “Able to be unlocked.” A 2 A A un 2 V A lock -able “Not able to be locked.” (2) The following sentence has two possible meanings. Please draw a tree for each meaning and paraphrase the meaning of each tree. Then, tell me (for each tree) what the PP is sister to. The girl watched the cat from the tall building. S qp NP VP 3 4 D N VP PP The girl 3 rp V NP P NP watched 2from r1o D N D A N the cat the tall building The girl watched the cat. She did her watching while in a tall building. The PP ‘from the tall building’ modifies the VP ‘watched the cat.’ S qp NP VP 3 3 D N V NP The girl watched r1p D N PP the cat rp P NP from r1o D A N the tall building The girl watched cat. Specifically, she watched the cat the came from the tall building. The PP ‘from the tall building’ modifies the N ‘cat.’ 8 3.0 Big Question 3: How are languages similar? How can they be different? - A big issue that we addressed this semester was while there are many, many languages in the world (~6000), we find features or tendencies that are common to all (or nearly all) languages. Linguistic Universals (i) Phonology: - Maximum Onset Principle: Make onsets to syllables as large as possible. - Sonority Sequencing Principle: (http://blogs.umass.edu/eba/files/2012/01/201Spring-Phonological-Rules.pdf) - Place and Manner of Articulation Assimilation: Languages tend to have (ii) Morphology: - Morpheme Ordering Constraint: Derivational morphemes combine with words before inflectional morphemes. Derivational morphemes cannot combine with a word that has already combined with inflectional morphemes. (iii) Syntax: - Subject always precedes object - Furthermore, even when languages are different from each other (e.g., Japanese vs. English), we find that they vary in constrained ways. o E.g., if a language has the rule VP V NP, it will also have the rule PP P NP. That would be a HEAD-INITIAL language like English. If a language has the rule VP NP V, it will also have the rule PP NP P. That would be a HEAD-FINAL language like Japanese. - Linguists have a particular conception of Universal Grammar called the Principles and Parameters theory. o PRINCIPLE: Finite set of linguistic universals; the part of grammar common to all speakers. o PARAMETER: Options for which a language can have different settings (e.g., HEADINITIAL vs. HEAD-FINAL). What kinds of evidence led linguists to posit an approach like Principles and Parameters and Universal Grammar? Language acquisition: Children are able to acquire languages rapidly and with limited, imperfect input (‘Poverty of the Stimulus’). Creoles: When new languages are developing without fluent bilinguals, new features develop in the resulting creoles. When linguists compare many creoles, they find features in common, even though the languages were formed in very different places or from different languages. Language universals: There are limits on the types of language variation found. There are properties that all languages have in common. 9 10