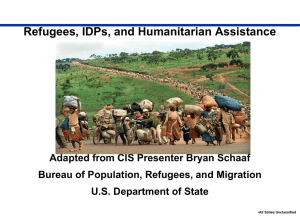

The Problem of Refugees in The Light of Contemporary International

advertisement