the law of quebec

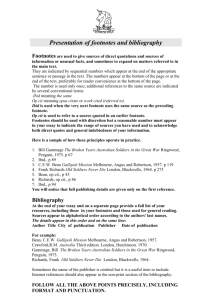

advertisement

THE LAW OF QUEBEC INTRODUCTION Engineers involved in construction projects in the Province of Quebec should take note that there are certain fundamental differences between the laws applicable in the Province of Quebec and the laws applicable in the common-law provinces. Numerous statutes adopted by the National Assembly of Quebec contain specific provisions which apply to construction projects. These statutes govern such matters as the professional qualification of contractors, the qualification of construction workers, health and safety on the work site, protection of the environment and safety requirements for public buildings. The Engineers Act1 of Quebec enumerates the services which constitute the exclusive field of practice of an engineer. It also provides that the members of the Ordre des ingénieurs du Québec are governed by the Professional Code.2 The Professional Code states that the principal function of each professional order must be to ensure the protection of the public. A person who is a member of a Canadian association of engineers or who holds a diploma recognized by the Ordre des ingénieurs du Québec, may, providing certain requirements are met, obtain a temporary licence for a specific project3 or a recognition of equivalence of a diploma issued by an educational establishment outside Quebec.4 It is to be noted that members of the Ordre des ingénieurs du Québec must be covered by a professional liability insurance policy5 and must, amongst other requirements, have an “appropriate knowledge” of the French language.6 Many provisions of law which govern the performance of engineering services in the Province of Quebec, including such matters as the liability of engineers to their clients and to third parties, are contained in the Civil Code of Quebec. 1 R.S.Q., c. I-9 (R.S.Q. is the abbreviation for Revised Statutes of Quebec). 2 R.S.Q., c. C-26. 3 Engineers Act, sections 18 and 19. R.S.Q., c. C-26. 4 Regulation respecting the standards for equivalence of diplomas and training for the issue of a permit by the Ordre des ingénieurs du Québec, R.S.Q., c. I-9, r. 7.2 (0.C. 381-2002). 5 Règlement sur l’assurance-responsabilité professionnelle des membres de l’Ordre des ingénieurs du Québec, R.R.Q., c. I19, r. 1.1.1. 6 Regulation respecting other terms and conditions of the issuance of permits by the Ordre des ingénieurs du Québec, R.R.Q., c. I-9, r.1.3. -2– THE CIVIL CODE OF QUEBEC The Civil Code of Quebec is considered the cornerstone of the Quebec civil law system. This is confirmed by the preliminary provision of the Civil Code which reads as follows: 7 The Civil Code of Quebec, in harmony with the Charter of human rights and freedoms and the general principles of law, governs persons, relations between persons, and property. The Civil Code comprises a body of rules which, in all matters within the letter, spirit or object of its provisions, lays down the jus commune, expressly or by implication. In these matters, the Code is the foundation of all other laws, although other laws may complement the Code or make exceptions to it. In order to protect their interests and the interests of their clients when doing business in the Province of Quebec, engineers should have a basic understanding of the provisions of the Civil Code which are likely to apply to the conclusion and execution of construction contracts. CONTRACTUAL AND EXTRACONTRACTUAL LIABILITY Under Quebec law, liability exists when there is a breach of an obligation. An obligation can arise from a contract or from any act or fact to which the effects of an obligation are attached by law. An obligation which arises from a contract is a contractual obligation, whereas an obligation which arises from the law is referred to as an extracontractual obligation. The Civil Code provides that every person has a duty to abide by the rules of conduct which apply to him or her according to the circumstances, usage or law so as not to cause injury to another person. When a person fails to respect this duty, he or she is responsible for any bodily, moral or material injury he or she causes to another person.8 The Courts will exercise their discretion in deciding whether or not a particular act or omission constitutes a breach of an obligation. In professional liability cases, the Courts will consider how a normally prudent and competent member of the same profession would have acted under the same circumstances. The Civil Code also states that in certain cases a person may be held liable for the injuries caused to another by the act or fault of another person. For example, an employer can be 7 The Civil Code of Quebec came into force on January 1, 1994. It replaced the Civil Code of Lower Canada which had originally been adopted in 1865. 8 Civil Code, art. 1457. - 3 – held responsible for the injuries or damages caused by its employee.9 Furthermore, there is a presumption of liability against a person for damages caused by property in his or her custody.10 INTERPRETATION OF CONTRACTS The Civil Code contains numerous provisions dealing with the interpretation of contracts. Certain provisions reflect a desire to protect the consumer and the party who signs a "contract of adhesion". A contract of adhesion is one where the terms are imposed or drafted by one party without the other party having the opportunity of negotiating or changing them.11 The classification of a contract as a consumer contract or a contract of adhesion will have an impact on the interpretation of the effects of the contract. For example, in the case of a consumer contract or a contract of adhesion, an external clause referred to in the contract will be deemed null i f at the time of the conclusion of the contract it was not brought expressly to the attention of the consumer or the adhering party, unless the other party proves that the consumer or adhering party otherwise knew of it.12 Engineers who are involved in the drafting of contracts for construction projects in the Province of Quebec should be aware of this provision and should ensure that all documents and clauses to which the contract refers form part of the contract documents. I f this is not practical, then the consumer or adhering party should acknowledge in writing that the external clause referred to in the contract was expressly brought to his or her attention. The Civil Code also states that in a consumer contract or contract of adhesion, a clause which is illegible or incomprehensible to a reasonable person is null i f the consumer or the adhering party suffers a prejudice as a result thereof. Evidence that an adequate explanation of the nature and scope of the clause was given to the consumer or adhering party would, however, constitute a valid defense to such a claim.13 In a consumer contract or contract of adhesion, a clause which is excessive or unreasonably detrimental to the consumer or the adhering party may be considered abusive in which case it can be declared null or the obligation arising from it may be reduced.14 These provisions of the Civil Code give the Courts the power to reduce the contractual obligations of a party in certain circumstances. Care must therefore be taken in the 9 Ibid. art. 1463. 10 Ibid. art. 1465. 11 Ibid. art. 1379. 12 Ibid. art. 1435. 13 Ibid. art. 1436. 14 Ibid. art. 1437. - 4 – drafting of contracts, to avoid the inclusion of clauses that may be considered by a Court to be illegible, incomprehensible or abusive. LIMITATION OF LIABILITY A person may not exclude or limit his or her liability for material damages caused to another through an intentional fault or gross negligence nor is it possible to exclude or limit one's liability for bodily or moral injury.15 A notice stipulating the exclusion or limitation of the obligation to repair an injury resulting from the non-performance of a contractual obligation is only valid i f the party invoking the notice proves that the other party was aware of its existence at the time the contract was formed.16 A person may not by way of a notice limit or exclude his or her obligation to repair the injury caused to a third person, but such a notice may constitute a warning of danger.17 FORCE MAJEURE The Civil Code provides that a person may exculpate himself or herself from liability for injury caused to another by proving that the injury results from an unforseeable and irresistible event.18 The appreciation of what constitutes a case of Force majeure is left to the discretion of the Courts. DISCLOSURE OF TRADE SECRETS A person may exculpate himself or herself from liability for injury caused to another as a result of the disclosure of a trade secret by proving that considerations of general interest prevail over keeping the secret and, particularly, that its disclosure was justified for reasons of public health or safety.19 Although this provision may not necessarily receive application in construction matters, it does confirm the importance which the Civil Code attaches to the health and safety of the public. 15 Ibid. art. 1474. 16 Ibid. art. 1475. 17 Ibid. art. 1476. 18 Ibid. art. 1470. 19 Ibid. art. 1472. - 5 – SOLIDARITY Where several persons have jointly taken part in a wrongful act which has resulted in an injury, or i f they committed separate faults each of which may have caused the injury, and where it is impossible to determine which of them actually caused it, they are solidarily (jointly and severally) liable for reparation thereof.20 An obligation is solidary (joint and several) between debtors where they are obligated to the creditor for the same thing in such a way that each of them may be compelled separately to perform the entire obligation and where performance by a single debtor releases the others towards the creditor.21 Solidarity between debtors exists where it is expressly stipulated by the parties or imposed by law. It is presumed to exist where an obligation is contracted for the performance of a service or an organized economic activity.22 Engineers who participate in the execution of construction projects as a member of a joint venture should therefore consider to what extent they may be held solidarily liable for the faults of the other members of the joint venture. The obligation to repair the injury caused to another through the fault of two or more persons is solidary where the obligation is extracontractual.23 REMEDY FOR NON-PERFORMANCE An obligation gives the creditor the right to demand that it be performed in full, properly and without delay. When the debtor fails to perform his or her obligation without justification, the creditor may either force specific performance of the obligation or obtain, in the case of a contractual obligation, the resolution or resiliation of the contract. The creditor can also ask for the reduction of the creditor’s own obligations.24 If the debtor fails to respect his or her obligations, the creditor may perform the obligation or cause it to be performed at the expense of the debtor. A creditor wishing to do so must first put the debtor in default except in cases where the debtor is in default by operation of the law or by the terms of the contract.25 20 Ibid. art. 1480. 21 Ibid. art. 1523. 22 Ibid. art. 1525. 23 Ibid. art. 1526. 24 Ibid. art. 1590. 25 Ibid. art. 1602. - 6 – This would apply, for example, in the case where a contractor fails to properly execute a construction contract. After having put the contractor in default, the owner can have the work completed by another contractor and claim any additional cost from the defaulting contractor. ASSESSMENT OF DAMAGES A creditor is entitled to damages for bodily, moral or material injuries which are an immediate and direct consequence of the debtor’s default.26 The obligation of the debtor to pay damages to the creditor is neither reduced nor altered by the fact that the creditor receives compensation from a third person as a result of the injury the creditor has sustained, except i f the third party is subrogated in the rights of the creditor.27 An example of such a case is where the creditor who suffers a loss is indemnified by his or her insurance company. The damages awarded to the creditor are intended to compensate the amount of the loss the creditor has sustained and the profit of which the creditor has been deprived. Future loss which is certain and can be assessed is taken into account in awarding damages.28 For example, i f a contractor's negligence results in the late completion of the construction of an apartment building, the owner can claim compensation for loss of revenue i f the owner can prove that the apartments would have been rented immediately upon completion of the work. In contractual matters, the debtor is only liable for damages that were foreseen or foreseeable at the time the obligation was contracted unless the non-performance of the obligation is the result of an intentional fault or gross negligence. Even then, only damages which are an immediate and direct consequence of the non-performance will be awarded.29 PENAL CLAUSES A penal clause is a clause in virtue of which the parties assess the anticipated damages by stipulating that the debtor will pay a penalty i f the debtor fails to perform the debtor's obligation. The creditor can avail himself or herself of the penal clause instead of enforcing the specific performance of the obligation, but in no case may the creditor claim both the performance of the obligation and the penalty unless the penalty has been stipulated for a mere delay in the performance of the obligation.30 For example, i f a contractor is late in the completion of the construction of a building and the contract contains a penalty clause for late delivery, the owner can require the contractor to complete the construction and the owner may in addition claim the penalty for late delivery. 26 Ibid. art. 1607. 27 Ibid. art. 1608. 28 Ibid. art. 1611. 29 Ibid. art. 1613. 30 Ibid. art. 1622. - 7 - MANUFACTURER'S LIABILITY The manufacturer of a product is liable for the injury caused to a third person by reason of a safety defect in the product. The same rule applies to a person who distributes the product under his or her name or as his or her own product, and to any supplier of the product.31 A product is deemed to have a safety defect i f it does not afford the safety which a person is normally entitled to expect, by reason of a defect in the design or manufacture of the product, the preservation or the presentation of the product, or the lack of sufficient indications as to the risks, dangers or safety precautions.32 The seller of a product must warrant to the buyer that the product and its accessories are, at the time of sale, free of latent defects which render it unfit for the use for which it was intended or which so diminish its usefulness that the buyer would have not bought it, or paid such a high price had the buyer been aware of them. The seller, however, is not bound to warrant against any apparent defect, or latent defect known to the buyer.33 A defect is presumed to have existed at the time of a sale by a professional seller i f the product malfunctions or deteriorates prematurely in comparison with products of the same type. Such a presumption does not apply i f the defect is due to improper use of the property by the buyer.34 The manufacturer, any person who distributes the property under his or her name or as his or her own, and any supplier of the property, in particular the wholesaler and the importer, are also bound to warrant the buyer in the same manner as the seller.35 THE CONTRACT OF ENTERPRISE OR FOR SERVICES The contract of enterprise or for services is a contract by which a person, referred to as the contractor, or the provider of services (such as an engineer), undertakes to carry out physical or intellectual work for a client, or undertakes to provide a service for a price which the client agrees to pay.36 One of the major differences between the contract of enterprise or for services and the contract of employment is that the contractor, or the provider of services, is free to choose the 31 Ibid. art. 1468. 32 Ibid. art. 1469. 33 Ibid. art. 1726. 34 Ibid. art. 1729. 35 Ibid. art. 1730. 36 Ibid. art. 2098. - 8 – method of performance of the contract and no relationship of subordination exists between the contractor, or the provider of services, and the client in respect of such performance.37 The contractor and the provider of services must act with prudence and diligence and in the best interest of their client. Depending on the nature of the work, they are bound to act in accordance with the practice of the trade, the rules of the art and the terms of the contract.38 Before the contract is entered into, the contractor and the provider of services are bound to provide to the client, as far as the circumstances permit, any useful information concerning the nature of the work which they undertake to perform and the property and time required for the task.39 Therefore, the engineer has the obligation to furnish all relevant information to the client concerning the performance of the contract even i f the client does not ask for it. The determination of the information which must be furnished is left to the discretion of the Courts and depends on the circumstances of each case. When the price of the work or services is fixed by the contract, the client must pay this price and the client cannot claim a reduction on the grounds that the work or services cost less than anticipated. On the other hand, in the case of a fixed price contract, the contractor and the provider of services may not claim an increase in the price of the contract even i f the work or services cost more than had been anticipated. In the case where the price of the work is estimated at the time the contract is entered into, the contractor or provider of services must justify any increase in the price. PRESUMPTION OF LIABILITY The provisions of the Civil Code cited below establish a presumption of liability applicable to the parties who participate in the construction of a building; these provisions of the Civil Code are considered to be of public order and may not be derogated from, even by private agreement: 2118. Unless they can be relieved from liability, the contractor, the architect and the engineer who, as the case may be, directed or supervised the work, and the subcontractor with respect to work performed by him, are solidarily liable for the loss of the work occurring within five years after the work was completed, whether the loss results from faulty design, construction or production of the 37 Ibid. art. 2099. 38 Ibid. art. 2100. 39 Ibid. art. 2102. - 9 – work, or the unfavourable nature of the ground. 2119. The architect or the engineer may be relieved from liability only by proving that the defects in the work or in the part of it completed do not result from any erroneous or faulty expert opinion or plan he may have submitted or from any failure to direct or supervise the work. The contractor may be relieved from liability only by proving that the defects result from an erroneous or faulty expert opinion or plan of the architect or engineer selected by the client. The subcontractor may be relieved from liability only by proving that the defects result from decisions made by the contractor or from the expert opinion or plans furnished by the architect or engineer. They may, in addition, be relieved from liability by proving that the defects result from decisions imposed by the client in selecting the land or materials, or the subcontractors, experts, or construction methods. The owner of a building which perishes in whole or in part within five years after completion can therefore rely on this presumption of liability of the architect, engineer, contractor and subcontractors without having to prove the precise cause of the loss. In order to rebut the presumption of liability, the architect, engineer, contractor and subcontractor have the burden of proving that they committed no fault, or that the defects result from a decision imposed by the client. Article 2120 of the Civil Code stipulates that the contractor, the architect and the engineer, in respect of work they directed or supervised, and where applicable, the subcontractor in respect of work the subcontractor performed, are jointly liable to the owner for defects due to poor workmanship, which exist at the time of acceptance of the work, or which are discovered within one year after acceptance. They are therefore only responsible to the owner for their proportionate share of the cost of the repairs.40 For example, i f an architect, an engineer and a contractor are involved, each would be responsible for one-third of the cost. The architect or the engineer who does not direct or supervise the work is only liable for the loss occasioned by a defect or error in the plans or the expert opinions furnished by the architect or engineer. LEGAL HYPOTHECS A hypothec is a real right affecting moveable or immovable property. It gives the creditor the right to exercise his rights against the property even i f it has changed hands; it also gives the creditor the right to take possession of the property, to take it in payment, to sell it or 40 Ibid. art. 1518. - 10 – cause it to be sold and in such a case to receive the proceeds of the sale by preference, according to the rank determined in the Civil Code.41 A legal hypothec in favour of persons who take part in the construction or renovation of an immovable (building) can only affect that immovable. It exists in favour of the architect, engineer, supplier of materials, workmen and contractor or subcontractors for the work requested by the owner of the immovable and for the materials or services supplied or prepared for such work.42 The legal hypothec in favour of persons taking part in the construction or renovation of an immovable subsists for a period of 30 days after the work has been completed. It continues to subsist if, before the 30-day period expires, a notice describing the affected immovable and indicating the amount of the claim is registered in accordance with the relevant formalities. The notice must be served on the owner of the immovable. The legal hypothec will become extinguished six months after the work is completed unless the creditor publishes an action against the owner of the immovable or registers a prior notice of exercise of the creditor's hypothecary right.43 The hypothec secures the increase in the value added to the immovable by the work, materials or services supplied or prepared for the project. However, where the persons in whose favour it exists did not enter into a contract directly with the owner, the hypothec is limited to the work, materials or services supplied after written notification of the contract to the owner. Subcontractors and suppliers of materials who enter into a contract with the general contractor must therefore give a written notice to the owner of the immovable before commencing the work in order to T4reserve their right to register a legal hypothec Workmen are not required to give such a notice.44 At the request of the owner of the property affected by a legal hypothec, the Courts may authorize the substitution of another form of security in order to guarantee payment to the creditor.45 Engineers who administer construction contracts for their clients must take the necessary precautions in order to ensure that the parties who have the right to register legal hypothecs are paid for their work and services. Otherwise, these creditors may register legal hypothecs against the property and oblige the owner to satisfy their claims. I f the contractor is insolvent, the owner may never be able to recover these amounts from him. 41 Ibid. art. 2660. 42 Ibid. art. 2726. 43 Ibid. art. 2727. 44 Ibid. art. 2728. 45 Ibid. art. 2731. - 11 – The right to register a legal hypothec also benefits the engineer i f the engineer fees for professional services are not paid. CONCLUSIONS It is impossible to summarize all the important provisions of law applicable to construction projects in Quebec. Accordingly, comments have been provided on selected aspects of the law contained in the Civil Code which are most likely to be of interest to an engineer involved in a project in the Province of Quebec. It is wise to seek legal advice from an expert in the field as soon as a litigious situation arises. It is even wiser to seek legal advice at the contract review stage, since many problems of interpretation and many claims can be avoided by the use of properly drafted contract documents. OLIVIER F. KOTT, Senior Partner May 4, 2007