Before NASCAR: The Corporate and Civic

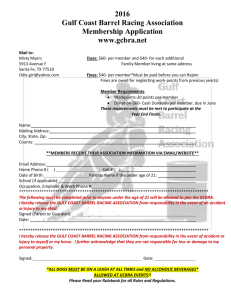

advertisement