distance education

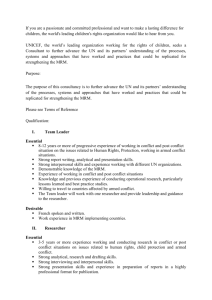

advertisement