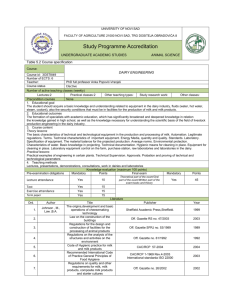

key market signals for the dairy industry may 2015 - Tip-Top

advertisement