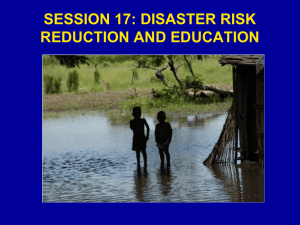

Disaster risk reduction NGO inter-agency group learning

advertisement