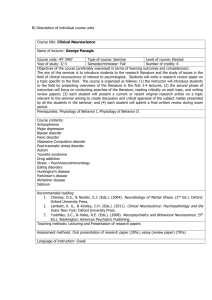

preprint manuscript

advertisement