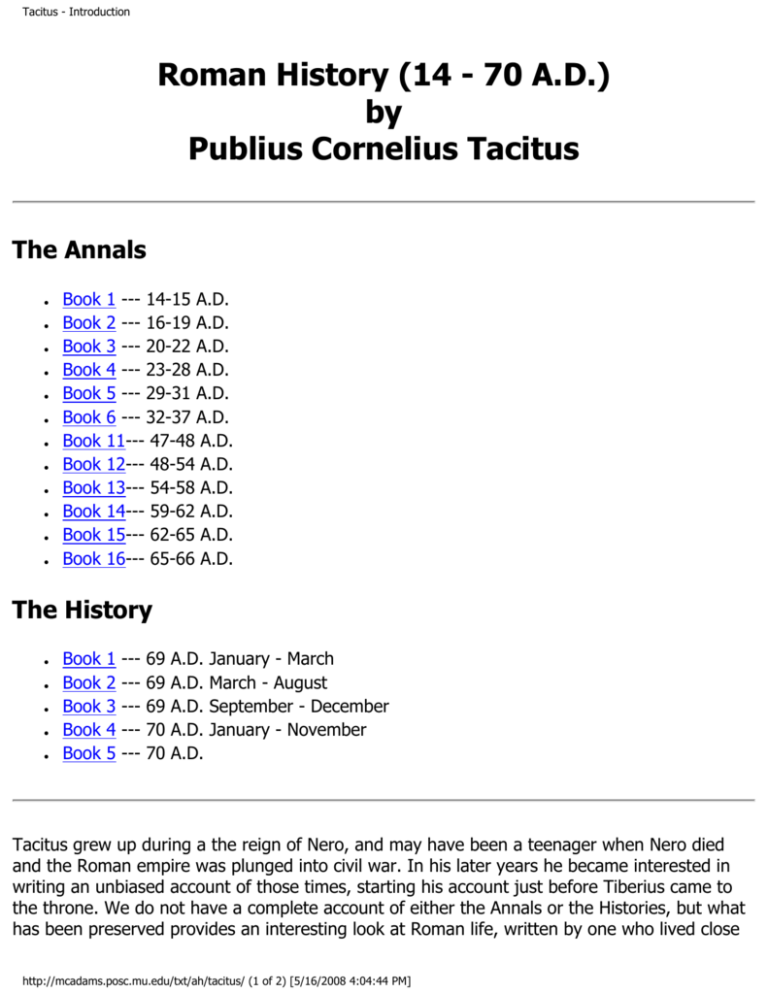

Roman History Tacitus

advertisement