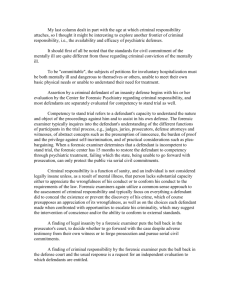

Cultural Pluralism in Criminal Defense: An Inner Conflict of the

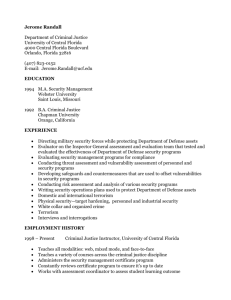

advertisement